![]() Okay, question time: Imagine you’re a major national newspaper whose crosstown archrival has somehow obtained two million pages of explosive documents that outed your country’s biggest political scandal of the decade. They’ve had a team of professional journalists on the job for a month, slamming out a string of blockbuster stories as they find them in their huge stack of secrets.

Okay, question time: Imagine you’re a major national newspaper whose crosstown archrival has somehow obtained two million pages of explosive documents that outed your country’s biggest political scandal of the decade. They’ve had a team of professional journalists on the job for a month, slamming out a string of blockbuster stories as they find them in their huge stack of secrets.

How do you catch up?

If you’re the Guardian of London, you wait for the associated public-records dump, shovel it all on your Web site next to a simple feedback interface and enlist more than 20,000 volunteers to help you find the needles in the haystack.

Your cost for the operation? One full week from a software developer, a few days’ help from others in his department, and £50 to rent temporary servers.

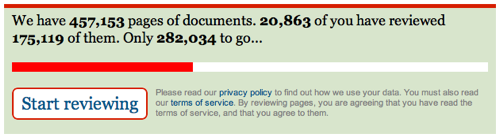

Journalism has been crowdsourced before, but it’s the scale of the Guardian’s project — 170,000 documents reviewed in the first 80 hours, thanks to a visitor participation rate of 56 percent — that’s breathtaking. We wanted the details, so I rang up the developer, Simon Willison, for his tips about deadline-driven software, the future of public records requests, and how a well-placed mugshot can make a blacked-out PDF feel like a detective story.

He offered four big lessons:

— Your workers are unpaid, so make it fun. Willison started coding one week before the Thursday launch date, teamed with a designer on Tuesday, a system administrator on Wednesday and leaned on everyone in his 15-person department for ad-hoc help on Thursday. But the bulk of the labor would come from Guardian readers.

— Your workers are unpaid, so make it fun. Willison started coding one week before the Thursday launch date, teamed with a designer on Tuesday, a system administrator on Wednesday and leaned on everyone in his 15-person department for ad-hoc help on Thursday. But the bulk of the labor would come from Guardian readers.

How to lure them?

By making it feel like a game, said Willison, 28. The Guardian’s four-panel interface — “interesting,” “not interesting,” “interesting but known,” and “investigate this!” made categorization easy. And the progress bar on the project’s front page, immediately giving the community a goal to share.

But a video game needs more than an interface and a score. It needs a narrative — and this project offered that, too.

That was what Willison discovered when, on a whim, he added the Guardian’s mugshots of each MP to their pages in the database. Participation shot up, he said.

“There’s that wonderfully personal element, because everybody in the U.K. has an MP,” Willison said. “You’ve got this big smiling face looking at you while you’re digging through their expenses.”

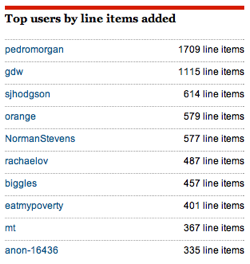

On Monday, to add a competitive edge, Willison posted lists of the top-performing volunteers. By that point, the project had drawn 36,000 unique visitors and 20,440 participants.

On Monday, to add a competitive edge, Willison posted lists of the top-performing volunteers. By that point, the project had drawn 36,000 unique visitors and 20,440 participants.

“Any time that you’re trying to get people to give you stuff, to do stuff for you, the most important thing is that people know that what they’re doing is having an effect,” Willison said. “It’s kind of a fundamental tenet of social software. … If you’re not giving people the ‘I rock’ vibe, you’re not getting people to stick around.”

— Public attention is fickle, so launch immediately. Before Parliament released its records Thursday, Willison’s team thought they might be able to postpone their launch to Friday if necessary. When they saw Thursday’s newsbroadcasts, they realized they’d been wrong. The country’s imagination was caught.

“It became quickly clear on Thursday that it was a huge story, and if we failed to get it out on Thursday, we’d lose a lot of momentum,” Willison said.

The result: No time to load-test the program, perfect the interface, or even set up a system for Guardian reporters to view the vast amount of data that started pouring into their servers. (The first overview wasn’t ready for publication until Monday.)

Some programmers would be uncomfortable in those circumstances. Welcome to journalism, folks.

“We kind of load-tested it with our real audience, which guarantees that it’s going to work eventually,” Willison said impishly. “It’s a very realistic way of debugging the application.”

— Speed is mandatory, so use a framework. Willison’s project was built on Django, the custom Web framework “for perfectionists with deadlines” that he and Adrian Holovaty created for the Lawrence Journal-World. In the world of database programming, a framework is like an offset press: hard to build — Django 1.0 required three years of open-source development — but once it’s set up, there’s no faster way to churn out content. Hand-coding an application like the Guardian’s would have been like publishing a daily newspaper with movable type.

— Speed is mandatory, so use a framework. Willison’s project was built on Django, the custom Web framework “for perfectionists with deadlines” that he and Adrian Holovaty created for the Lawrence Journal-World. In the world of database programming, a framework is like an offset press: hard to build — Django 1.0 required three years of open-source development — but once it’s set up, there’s no faster way to churn out content. Hand-coding an application like the Guardian’s would have been like publishing a daily newspaper with movable type.

Other frameworks and languages would have worked, too. “You absolutely could build this in Ruby on Rails or in PHP,” Willison said, but “as far as I’m concerned, this is absolutely Django’s sweet spot. This is absolutely what Django is designed to do…Once I had a designer and a client-side engineer working on the project, I could really just hand it over to them and I didn’t have to worry about the front-end code any more.”

— Participation will come in one big burst, so have servers ready. As well as the Guardian’s first Django joint, this was its first project with EC2, the Amazon contract-hosting service beloved by startups for its low capital costs.

Willison’s team knew they would get a huge burst of attention followed by a long, fading tail, so it wouldn’t make sense to prepare the Guardian’s own servers for the task. In any case, there wasn’t time.

“The Guardian has lead time of several weeks to get new hardware bought and so forth,” Willison said. “The project was only approved to go ahead less than a week before it launched.”

With EC2, the Guardian could order server time as needed, rapidly scaling it up for the launch date and down again afterward. Thanks to EC2, Willison guessed the Guardian’s full out-of-pocket cost for the whole project will be around £50.

As for the software, it was all open-source, freely available to the Guardian — and to anyone else who might want to imitate them. Willison hopes to organize his work in the next few weeks.

“There’s a lot of stuff in there that’s potentially reusable,” Willison said.

Photo of Willison by Matt Patterson used under a Creative Commons license.