BEIJING — Yeeyan.org has 150,000 registered users, who collectively translate 50 to 100 news articles every day from English to Chinese. Since its inception in 2006, the site has grown into a key gateway for Chinese speakers who want to follow international news. It has been so successful that it has attracted the attention of major news sources like The Guardian and ReadWriteWeb — and also the Chinese government, which abruptly shut Yeeyan down last year for several months.

BEIJING — Yeeyan.org has 150,000 registered users, who collectively translate 50 to 100 news articles every day from English to Chinese. Since its inception in 2006, the site has grown into a key gateway for Chinese speakers who want to follow international news. It has been so successful that it has attracted the attention of major news sources like The Guardian and ReadWriteWeb — and also the Chinese government, which abruptly shut Yeeyan down last year for several months.

But this is not a story about China. I believe that Yeeyan is pioneering cost-effective solutions to a major global problem: the ghettoization of information by language. This is a change with potentially far-reaching implications for journalism. I met Kitty Wang, the vice general manager, and Walter Wang, Yeeyan’s community manager (no relation), in a Beijing cafe and asked them to explain to me how Yeeyan works, from technological, social, and business perspectives.

The name Yeeyan derives from the Chinese characters 译 (yi) and 言 (yan), which together mean something like “translate the information,” and Kitty and Walter told me that the site’s primary aim is to increase the flow of information between cultures. Yeeyan.org looks like a news site, with headlining photos and editor-selected hot stories on the front page. (English readers can check out the Google translation.) Stories are arranged into typical sections such as business, sports, technology, and life. The difference is that all of the Chinese-language material on the site has been translated from English sources by members of the Yeeyan community, almost always for free.

The success of the site in producing a continual stream of translations — over 60,000 so far — is the result of careful community management and well-designed social features. And it’s a model that seems like it could be replicated for other languages.

Aside from reading stories, users can perform two basic actions: recommend a story or a URL for translation, or translate a recommended story. All visitors to the site are readers, many are recommenders, and only a few thousand — a couple percent — actually create translations. That turns out to be enough, but Yeeyan’s existence depends on getting people to translate.

The site’s design encourages participation in a number of different ways. The front page prominently displays a staff-curated selection of recommended but as-yet-untranslated articles. Users can create “projects,” collections of articles around a specific topic, such as “foreign affairs,” “film lovers,” or “Toyota recall,” and active topics are featured on the front page. Each user has a profile which shows a history of their recommendations and completed translations, and a number of typical social networking features are supported, such as comments on articles and messages between users.

Yeeyan has also recently adopted a badge system, to encourage both participation and quality. There are automatically awarded badges for things like “most translations this week” and “most comments this week,” as well as a series of overall “levels” that users can attain by translating and commenting. Kitty says participation has shot up since the introduction of these incentives.

Yeeyan has also recently adopted a badge system, to encourage both participation and quality. There are automatically awarded badges for things like “most translations this week” and “most comments this week,” as well as a series of overall “levels” that users can attain by translating and commenting. Kitty says participation has shot up since the introduction of these incentives.

“Amazing ah?” says Kitty. “Even this little thing can intrigue passion.” As Napoleon once said, a soldier will fight long and hard for a bit of colored ribbon.

But clever software can never replace the involvement of human community managers. Yeeyan’s staff must read each translation before it is posted to ensure that it does not violate government taboos on reporting. (Since reopening in January, Yeeyan has dropped its “current events” category and now avoids all overtly political news, including stories from erstwhile partner The Guardian.) All websites in China are required to self-censor in this manner, but Yeeyan also takes this opportunity to interact with its translators.

“We are the first readers, so we comment first, we encourage users first, we proofread first,” says Kitty. “Those are all important to build up [the] community phenomenon.”

Kitty told me that there had been much early discussion over whether the site should publish only “good” translations, but in the end they decided that “the gate should be opened to everyone.” Part of their strategy is to encourage readers to become translators. Beginning translators tend to produce rough texts and make many mistakes, says Kitty, but “it is cruel if we don’t even provide a chance.” The policy occasionally drives good translators away from the site, but the Yeeyan team sees translator training as an important part of their social mission.

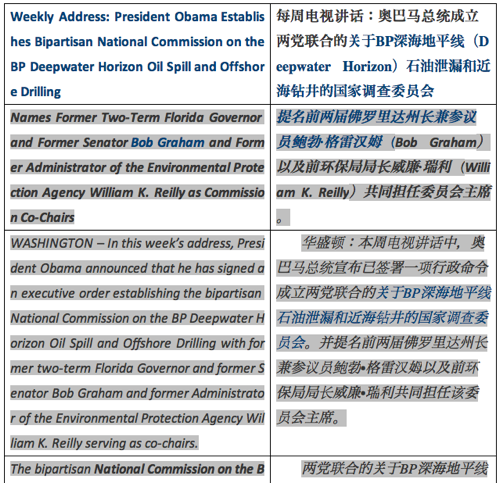

Nonetheless, Yeeyan has recently debuted a proofreading feature. The original text and a user translation are displayed side by side, and the proofreader can comment on each paragraph. Participation is encouraged by awarding badges for proofreading.

Under international law, permission from the copyright holder is generally required to create or publish a translation. By publishing user-supplied translations of arbitrary news material, Yeeyan creates a public good in a legally dubious fashion. But it’s worth remembering that many of the vital information services we now take for granted began on similarly vague principles. The web search engine could not exist without wholesale duplication of the entire web onto local servers, a move which was by no means obviously legal when the first commercial search engines appeared — and which some news organizations still aren’t sure about. The legality of Google scanning books is similarly being challenged.

Even so, Yeeyan is actively seeking agreements with copyright holders to create and publish translations of their work. “We do not want to use content for business illegally, but how to get authorization is a big problem,” Kitty said. “That’s why we are trying to talk to [copyright holders] to have win-win-win business model.”

The three parties in “win-win-win” are the content producer, Yeeyan, and the translator. Yeeyan has just such an agreement with ReadWriteWeb. All RWW articles are translated by a paid freelancer and posted on rwwchina.com, with the ad revenue split between Yeeyan and RWW.

Yeeyan is reluctant to put too much advertising on the main site, both because of the legal questions raised by commercial use of translations and for fear of alienating its all-volunteer community. But there’s money to be made offline if you have access to a huge pool of translation talent, and connections to publishers on both sides of the language divide. Yeeyan hopes to make its money out of brokering translations for foreign firms eager to enter the Chinese market, both online and offline. The company already handles the Chinese language versions of Men’s Health and several other magazines and has brokered more than 20 book deals. Translators are drawn from the best of Yeeyan’s volunteer talent pool. As an incentive to reach professional proficiency, translators who have earned the “Level 4” badge can apply to be Yeeyan partners. If approved, these skilled translators get the “Partner” badge, plus 3 RMB for every 1,000 views of their translated articles — and possibly a translation job offer later.

Yeeyan’s success raises broader questions for journalists and journalism. First, could the model be replicated? Could, say, the Associated Press cultivate a community that actively translated their reporting into other languages? I don’t see why not, though any organization that tried this would need a deep understanding of “community” and everything that implies — and deliver such an obvious public good that thousands of people would be willing to volunteer their time. The business model might also be different, but I can think of a number of ways to monetize a pool of translators and an audience eager for foreign-language news.

Yeeyan’s success raises broader questions for journalists and journalism. First, could the model be replicated? Could, say, the Associated Press cultivate a community that actively translated their reporting into other languages? I don’t see why not, though any organization that tried this would need a deep understanding of “community” and everything that implies — and deliver such an obvious public good that thousands of people would be willing to volunteer their time. The business model might also be different, but I can think of a number of ways to monetize a pool of translators and an audience eager for foreign-language news.

But suppose that a news organization was able to deliver a substantial amount of content to foreign-language audiences for very little cost, through communities like Yeeyan, or machine translation, or a combination of the two as in the hybrid World Wide Lexicon project. Such translations would not be up to professional quality initially — if ever — and publishers may be hesitant to endorse error-prone representations of their work. But asking about absolute accuracy and brand dilution misses the point — it’s like critiquing Wikipedia for its (improving) accuracy without discussing the net benefit to humanity. How would cheap translation change foreign reporting, and the very concept of international news? It’s a question which will soon be forced upon the profession by rising technological tides.

For the curious, and because I have repeatedly advocated that reporters make available their full source material, here’s a transcript of my followup IM chats with Kitty. In it we discuss further details of the site’s origin and operations, and their experience with the Chinese censors.