In his Times column this morning, David Carr wonders about the future of the Occupy Wall Street movement and, specifically, its fate as an ongoing topic of mass-media conversation. “Occupy Wall Street left many all revved up with no place to go,” he writes. Which is a problem, traditional-press-coverage wise, because: “In addition to the 5 W’s — who, what, when, where and why — the media are obsessed with a sixth: what’s next? Occupy Wall Street, for all its appeal as a story, is very hard to roll forward.”

That could be true (though “very hard,” of course, is quite different from “impossible”). And it could also be true that the features that may give Occupy, potentially, enduring power as a movement — its malleability, its permissiveness, its ability to act as an interface as well as an event — might also be the forces that, day to day, challenge its ability to convene attention. Particularly at the level of the mass culture.

It’s worth returning, for a moment, to the idea of trending topics algorithms, which reward discrete events over ongoing movements, favoring spikes over steadiness, effectively punishing trends that build, gradually, over time. (Which is to say: effectively punishing the notion of a “movement” itself.) This bias toward the spiky over the sticky is a defining feature, as well, of the daily workings of the traditional media (and of their great organizational mechanism, the Epiphanator): Occupy’s much-discussed lack of a singular identity has been not only kind of the whole point, but also, to some extent, the result of the way the movement has been mediated by a press that tends to reward newness over endurance. Occupy’s story — like all stories of ongoing political movements that are told by traditional producers of daily journalism — has been told episodically, in staccato rhythms that emphasize explosive ruptures in expectation. (“Expectation,” of course, being defined by the Epiphanator itself.) Occupy is, like so many other movements, subject to “the tyranny of recency.”

It’s worth returning, for a moment, to the idea of trending topics algorithms, which reward discrete events over ongoing movements, favoring spikes over steadiness, effectively punishing trends that build, gradually, over time. (Which is to say: effectively punishing the notion of a “movement” itself.) This bias toward the spiky over the sticky is a defining feature, as well, of the daily workings of the traditional media (and of their great organizational mechanism, the Epiphanator): Occupy’s much-discussed lack of a singular identity has been not only kind of the whole point, but also, to some extent, the result of the way the movement has been mediated by a press that tends to reward newness over endurance. Occupy’s story — like all stories of ongoing political movements that are told by traditional producers of daily journalism — has been told episodically, in staccato rhythms that emphasize explosive ruptures in expectation. (“Expectation,” of course, being defined by the Epiphanator itself.) Occupy is, like so many other movements, subject to “the tyranny of recency.”

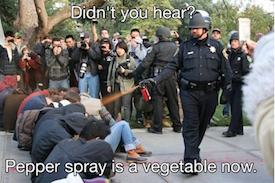

But that may well have just changed. This weekend, a series of photographs — images of a riot-gear-wearing cop shooting a group of students in the face with pepper spray — made their transition from journalistic documents to sources of outrage to, soon enough, Official Internet Meme. Perhaps the most iconic image (taken by UC Davis student Brian Nguyen, and shown above) isn’t explicitly political; instead, it captures a moment of violence and resistance in almost allegoric dimensions: the solidarity of the students versus the singularity of the cop in question, Lt. Pike; their steely resolve versus his sauntering nonchalance; the panic of the observers, gathered chorus-like and open-mouthed at the edges of the frame. The human figures here are layered, classified, distant from each other: cops, protestors, observers, each occupying distinct spaces — physical, psychical, moral — within the image’s landscape.

As James Fallows put it, “You don’t have to idealize everything about them or the Occupy movement to recognize this as a moral drama that the protestors clearly won.”

Exactly. The image — and its subsequent meme-ification — marked the moment when the Occupy movement expanded its purview: It moved beyond its concern with economic justice to espouse, simply, justice. It became as much about inequality as a kind of Platonic concern as it is about income inequality as a practical one. It became, in other words, something more than a political movement.

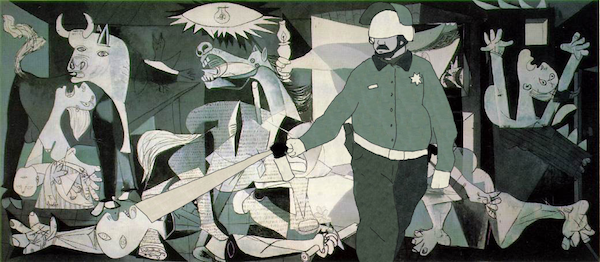

The image itself, I think — as a singular artifact that took different shapes — contributed to that transition, in large part because the photo’s narrative is built into its imagery. It depicts not just a scene, but a story. It requires of viewers very little background knowledge; even more significantly, it requires of them very few political convictions, save for the blanket assumption that justice, somehow, means fairness. The human drama the photo lays bare — the powerless being exploited by the powerful — has a universality that makes its particularities (geographical location, political context) all but irrelevant. There’s video of the scene, too, and it is horrific in its own way — but it’s the still image, so easily readable, so easily Photoshoppable, that’s become the overnight icon. It’s the image that offers, in trending topic terms, a spike — a rupture, an irregularity, a breach of normalcy. It’s the image that demands, in trending topic terms, attention.

The image itself, I think — as a singular artifact that took different shapes — contributed to that transition, in large part because the photo’s narrative is built into its imagery. It depicts not just a scene, but a story. It requires of viewers very little background knowledge; even more significantly, it requires of them very few political convictions, save for the blanket assumption that justice, somehow, means fairness. The human drama the photo lays bare — the powerless being exploited by the powerful — has a universality that makes its particularities (geographical location, political context) all but irrelevant. There’s video of the scene, too, and it is horrific in its own way — but it’s the still image, so easily readable, so easily Photoshoppable, that’s become the overnight icon. It’s the image that offers, in trending topic terms, a spike — a rupture, an irregularity, a breach of normalcy. It’s the image that demands, in trending topic terms, attention.

And it also demands participation. A key feature of the Epiphanator, the mechanism of press-mediated storytelling that defined our sense of the world for so long, is its impulse to organize time itself into discrete artifacts. Journalists tend to be obsessed with beginnings and, even more importantly, endings. This is how we make sense of things. What’s notable about the Lt. Pike image, though, is how dynamic its path has been — this despite the defining stillness of still photography — by way of the complementary filters of social media and human creativity.

The image of Pike (nom de meme: the Pepper Spray Cop) isn’t the first to reach a kind of iconic status when it comes to Occupy Wall Street. (It’s not even the first to involve pepper spray. See, for example, the horrific image of 84-year-old Dorli Rainey, her face dripping with burn-assuaging milk after being sprayed in Seattle.) But it is the first whose implicit narrative — one of struggle, one of outrage — offers viewers a kind of ethical, and tacitly emotional, participation in Occupy Wall Street. A moral drama that the protestors clearly won. Images, Susan Sontag argued, are “invitations” — “to deduction, speculation, fantasy.” They invite empathy, and, with it, investment.

It remains to be seen whether Pepper Spray Cop, as a singular image and a collection of derivatives, will prove enduring in the way that previous iconic photos — Phan Thi Kim Phúc, Tank Man — have done. But Pepper Spray Cop, and his ad hoc iconography, is a telling case study for observing what happens when political images become, in the social setting of non-traditional media, de- and then re-politicized. And it will be interesting to see whether the image’s viral life will affect David Carr’s question of “what’s next” for Occupy Wall Street in the world of traditional media. “Just a week ago,” NPR noted this morning, “it was starting to seem like the Occupy movement might be running short of fuel.” But “now that movement seems to have fresh energy after a week of police crackdowns across the country.”

Images by Brian Nguyen, Billy Galbreath, Kosso K, the Pepper Spraying Cop Tumblr, and UnlikelyWords.