When Jon Huang was younger he was the type of kid who spent his time making mods for Duke Nukem 3D. So it makes a kind of sense he’s now turned The New York Times into its own kind of shoot ’em up.

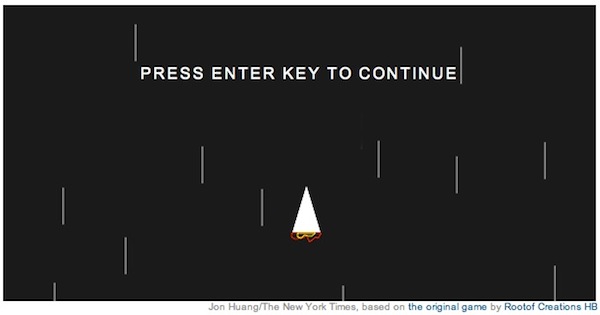

Huang was the multimedia producer behind the game embedded in the Times Magazine cover story on the addictive allure of “stupid games.” A reader stumbling on the story for the first time would see the video game feature at the top of the piece, be compelled to press the enter key, only to find they now have the ability to blast away various bits and elements of the story page itself. And it gets better: Your nondescript little ship can break outside the multimedia box and destroy all of the page, from the most-emailed stories (BOOM goes the DOWD!) to the navigational links and ads, right down to the “Inside NYTimes.com” promo. And, to the secret delight of editors everywhere, you can finally blast away commenters with impunity.

That surprise factor, mixed with the fact that it’s the Times having a little fun, has the Internet (or at least Planet Journalism in the Twitter universe) going bananas.

“I give all the credit to the guys behind Kick Ass. They’re a really excited pair of 18-year-old twins in Sweden,” Huang told me Wednesday. “I love that’s how the Internet works these days.”

Kick Ass is the open source game that made the Times’ interactive possible. It’s essentially a bookmarklet that allows you to wreak havoc on any given site you find yourself on. It was a perfect fit for the the theme of Sam Anderson’s Sunday magazine story, which examines the rise of games like Angry Birds, Plants vs. Zombies, and others that inhibit a world very different from what we might traditionally think of as regular video games.

Huang said they knew they wanted to create a game to go along with the story, specifically something that would surprise people by letting manipulate the story itself. The game is a part of the editorial message of the story. Want to know what it’s like to play a distracting, oddly addictive, and utterly unnecessary game? Try this one, Times reader. Huang said they knew they would have an audience that might not be familiar with the world of Bejeweled, Little Wings, or Words with Friends, so in order to entice them into the story, they’d offer up a game. “This is one of those rare circumstances where we can say we’re going to do something to let readers play the article and explain the journalism in a way,” Huang said.

In the discussions over the game they wanted to also draw inspiration from classic video games like Space Invaders, Tetris, and Breakout. Huang was a fan of the game from the Swedish sensations and began working to adapt its code for the Times. One of the biggest considerations was that they had to give readers instructions on how to play, and didn’t want to destroy the sharing tools and the text of the story itself. Beyond that, it was open ended.

“Originally we thought there would be a very strong push back and people would say this is not The New York Times,” he said. “But there’s been a lot of enthusiasm” — even from advertising, he told me. You would think of all the pixels involved on a web page, the advertising would be the last thing you would want to get rid of, especially in the journalism business. But Huang said the ad staff was on board, telling the multimedia team that if they couldn’t find cooperative clients they’d run house ads.

It would be hard to categorize Huang’s work at the multimedia desk: He’s now worked on interactives for everything from photo galleries of the war in Iraq to Kate Middleton’s dress to the Radiolab audio visualizer. Huang said multimedia features have become an integral part of the storytelling process at the Times, and as a result they’re often working with different departments, from the foreign desk to the dev team, at any given time. What makes all of that work, without stepping on toes or overreaching, Huang said, is the openness to experimentation.

In the case of Anderson’s magazine story, the game will likely be another element to help garner interest in the piece ahead of the Sunday paper. Of course, whether people are actually reading it or just trying to get a new high score while evaporating Google ads is another question. Huang said he expects most people will take the time to read the story, once they finally stop playing the game.

“We didn’t really think about that. Some people probably are just going to play,” he said. “But they may not be in the mood to read anyway.”