As comment bait goes, I’m a Gay Mormon Who’s Been Happily Married for 10 Years is a corker. That’s Gawker’s headline for a piece by Joshua Weed (excerpted from a longer version posted on Weed’s own site) about how he balances his homosexuality, his marriage to a woman, and his Mormon identity. Once up on Gawker, it quickly attracted several hundred comments.

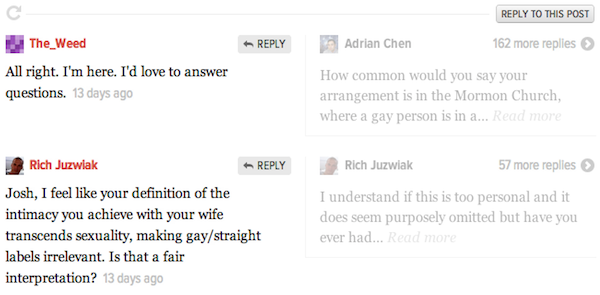

As you might imagine, some of those comments are moronic. One read, in its entirety, “lol mormons.” Some are grating: “…the idea of putting something in a slimy vagina is not sexy” (a comment since dismissed). Some are ad hominem: “This article is bullshit, by a self loathing brainwashed moron.” Of the hundreds of replies, however, the seven currently highlighted on the article page form a conversation between Weed himself and and a handful of other users; the replies are civil, thoughtful, and even, mirabile dictu, spell-checked. These seven replies don’t just happen to be highlighted — they are highlighted because they are part of a conversation.

Most news sites have come to treat comments as little more than a necessary evil, a kind of padded room where the third estate can vent, largely at will, and tolerated mainly as a way of generating pageviews. This exhausted consensus makes what Gawker is doing so important. Nick Denton, Gawker’s founder and publisher, Thomas Plunkett, head of technology, and the technical staff have re-designed Gawker to serve the people reading the comments, rather than the people writing them.

The technical choices here are simple, but their social ramifications are not. The new design dispenses with the tyranny of time order. On most systems, the most prominent comments are posted either by the most obsessed users (when comments are posted oldest first) or the drive-bys (newest first). On Gawker, a user who replies to an existing comment is likelier to get her contribution seen than an earlier user who added another reaction directly to the original post.

Gawker’s default assumption is that most comments won’t ever appear on the article page — like the Slashdot comment system, they are all there, but only accessible with extra work by the reader. This ensures that there is, by design, no way for regular participants (the Commentariat, a group Denton loathes) to use either volume or aggression to maximize attention. On Gawker (and, soon, on its seven sister sites), anyone can still say anything, but it’s no longer the case that anyone can say anything to everyone.

This lets Gawker to do less policing overall. If vapid or aggro comments are unlikely to make the main article page, Gawker can expand its support for anonymous comments, as with its burner accounts (a nod to the phones favored by drug dealers) and its instructions about how to report information anonymously.

They have been rolling out this system in pieces — burners and the ability of commenters to accept or dismiss replies came in April, shifting most comments off the main page happened in mid-June, and comment search is still coming. Remarkably, as the system has rolled out, it has proven to work even retroactively — a lovely Gawker piece by Maureen O’Connor, When My Mother and I Were Obsessed with Death, acquired its comments back in May, under the old system, but when the replies are sorted under the new system, the three featured comments (out of a hundred) add up to a heartfelt thousand-word coda, written by other women grappling with the same issues. If you view the same hundred comments in time order, you come across someone hitting on the author — “maureen you are so attractive, death-obsession is just the icing on the cake” — long before you find anything you’d care to read.

Gawker’s plan might fail, of course. When there are complicated user reactions to big posts, as with the Gay Mormon piece or John Cook’s recent Watergate post, the system buries many replies that are, to my eye, more thoughtful and engaged than the ones that made it to the main page, including many interesting replies by the posts’ authors, one of the things Denton explicitly hopes to highlight.

There are also real design challenges — the reader is supposed to understand that a grayed-out comment placed next to a featured one is an alternate response to the same parent comment. (It was confusing even to write that sentence; the current design doesn’t make it much clearer.) Conversations now have URLs, so readers can send traffic directly to a particular set of replies, but few people seem to understand or use this function. Comment search has yet to be launched. All these things will affect reader reactions.

There could also be deeper problems. On the list titled “This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things On The Internet,” Item #1 has always been human nature. The Commentariat, who know little about the subject of any given post, still have a lot of time on their hands, and they may yet come to dominate the new system. It may also be that readers are in fact as horrible as industry consensus has it, that without the bread and circuses of cursing and trolling, commenting will lose its appeal.

Many news sites seemed to have entered an endgame with their comment sections a year or so ago: give up on any real participation, give up on anonymity, fall back to “Login With Facebook.” This reaction has come about in part because comments on news sites have been stagnant for a long time. Gawker is demonstrating that a good part of that stagnation came about because the way readers have been asked to participate has been stagnant for a long time too.

Nick Denton photo by Matt Haughey used under a Creative Commons license.