We asked an array of people — hiring editors, recent graduates, professors, technologists, deans — to evaluate the job j-schools are doing and to offer ideas for how they might improve. Over the coming days, we’ll be sharing their thoughts with you. Here Eric Newton, senior adviser to the president at Knight Foundation, argues that journalism schools need to develop a culture of rapid change to keep up with the world around them.

Representatives from six foundations this summer wrote to the presidents at nearly 500 colleges in the United States, saying their journalism and mass communication education would get better if it could change faster. Together, we have invested hundreds of millions in programs at hundreds of campuses. We knew the digital age had turned our field upside down and inside out. But it had not done the same to journalism and communication education.

Schools that won’t change risk becoming irrelevant to private funders — and, more importantly, to the more than 200,000 students and the 300 million Americans they seek to serve. Without better-equipped graduates, how can we be sure future generations will have the news and information they need to run their communities and their lives?

We noted the digital age has disrupted traditional media economics, and that in America today there is a local journalism shortage. Thus, the “teaching hospital” model of journalism education — learning by doing in a teaching newsroom — seems promising. Students use digital media to inform and, hopefully, engage a community. This digital model requires top professionals in important positions in academia, treated equally with top scholars. Having more top professionals around would, for most schools, be a big change.

The funders didn’t think our letter was all that controversial. What’s the counterargument: that communication schools should ignore professionals, change slower, and get worse? Yet both the Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Education covered the letter. The journalism educators’ convention and the listservs buzzed.

Some educators said there was no need to talk of change: They’d already done it. Those folks missed the point. We’ve entered an era of continuous change. Did you change last year? You’re a year behind. Did you go digital in 2002? You’re a decade behind. The “we have changed” group includes those saying “our PhDs started out as professionals,” not realizing that folks from last century’s non-digital newsrooms are not the digital pros we’re talking about.

Others opined that we cared only about gizmos, not content. Yet smartphones are not a fad. Nor is social media or the World Wide Web. They are no more “gizmo” than the printing press was. They are driving a global revolution in digital content. For the first time in human history, billions of people are walking around with digital media devices linked into a common network.

A few professors claimed it was “anti-intellectual” to call for useful research, even if it helps us understand the technique, technology, and principles at work in this new age. When we asked about the major breakthroughs their theoretical papers had produced, or even who funds them, they fell silent. Yet we desperately need a change here: We need better research that helps us understand the science of engagement and impact.

The digital age is changing almost everything — who a journalist is, what a story is, which media work to provide news when and where people want it, and how we engage with communities. The only thing that isn’t changing is why. We still care about good journalism (and communications) because in the digital age they still are essential elements of peaceful, productive, self-improving societies.

Universities must be willing to destroy and recreate themselves to be part of the future of news. They should not leave that future to technologists alone. Journalism and communication schools must begin to change radically and constantly. Change to do what? To expand their role as community content providers; to innovate in digital technique and technology; to teach open, collaborative methods; and to connect to the whole university. The best schools realize that having top professionals on hand is as important as having top scholars. “Top” is the key word: Quality today does not mean a long career or a famous name. It means you are good at doing what you do in today’s environment. You don’t have to be a big school to make a difference. Look at Youngstown, Ohio, where students are providing community content as though they were attending Berkeley, USC, Missouri, or North Carolina.

Want a simple guide to a journalism or communications school? Look at its website. WordPress templates look better than many of them. Why is it acceptable for millions of Americans to communicate digitally in better-looking, more professional ways than the experts at universities?

There are hundreds of hard-working deans and directors, excellent applied researchers, brilliant professors, wonderful early adopters, growing numbers of digital innovators, and creative agents of change. To you, we say congratulations — you know how to change, so please, don’t stop. We need you to keep trying new story forms, teach data visualization, do computational journalism, develop entrepreneurial journalism, build new software, and even pioneer things like drone journalism. We need you to keep learning from the students, the first generation of digital natives, as fast as you teach them.

No institution within journalism education has achieved all that can be achieved. There are some big missing pieces. Journalism and communication schools could, for example, be some of the biggest and most important hubs on campuses. They could be centers for teaching 21st century literacy — news and civics literacy along with digital media fluency — to the entire student body. They could, but with only one or two exceptions, they aren’t. Yet democracy today is only as good as its digital citizens.

The News21 project at Arizona State shows us what’s possible in journalism education and why it’s important. This year’s investigation found only a tiny number of cases of voter fraud, raising questions about the legality of the organization that pushed for states to enact voter ID laws. Everyone from Jon Stewart to The Washington Post used the stories. This is student work and journalism education at its finest. It makes me optimistic, as Gingras was as he ended his talk at the journalism education convention in Chicago:

I believe we are at the beginnings of a renaissance in the exploration and reinvention of how news is gathered, expressed, and engaged with. But the success of journalism’s future can only be assured to the extent that each and every person in this room helps generate the excitement, the passion, and the creativity to make it so. May you enjoy the journey, and more importantly, might you inspire others to enjoy theirs.

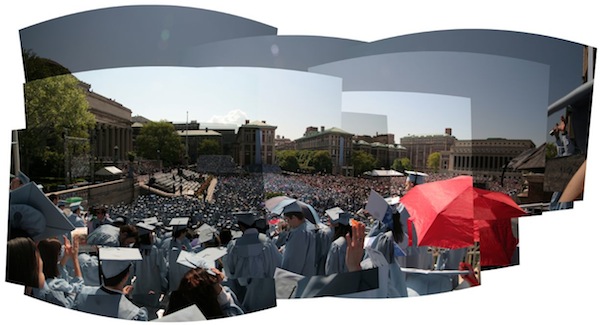

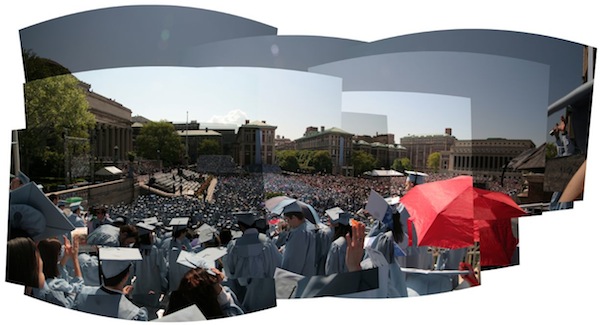

Panorama of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism commencement by Lam Thuy Vo used under a Creative Commons license.