There were lots of little cupcakes and big hugs in the wake of Kickstarter success for Laura and Chris Amico, who last month surpassed their $40,000 fundraising goal to keep Homicide Watch D.C. running. The Amicos recently moved up here to Cambridge for Laura’s 10-month Nieman-Berkman Fellowship at Harvard, so they had to let go of their two-year-old reporting project to mark every homicide in Washington, D.C.

Laura and Chris will be the first to tell you that, elated and grateful as they are about the funding, Kickstarter success doesn’t by any means guarantee success in the long term. “We need to find a path to sustainability for the D.C. site, independent of Kickstarter,” Chris told me. Kickstarter, if successful, gives projects a one-time crowdfunded cash infusion to sustain a project with a fixed end-point — but it’s not a business model for journalism. The work of most newsrooms is intended to be ongoing and not completable in the way, say, a single documentary film or album can be completed.

For the Amicos, a Kickstarter campaign was a way to buy time. They’re able to turn over their crime reporting project to university students, who will get paid to keep it running for the next year.

“Preparation beats passion. Being passionate is less successful than being prepared.”

“The first 24 hours of the campaign, we were like, ‘Oh my god, we’re 24 percent of the way in 24 hours, we’re going to get this in a week,'” Laura says. “But then we had this week when it was just dead. There was at least one day when we didn’t have any donations at all. We had given up. We were like, ‘This is not happening. We have 10 days to go. We’re less than halfway.'” (In order to get any funding at all on Kickstarter, you have to hit your goal amount.)

Then writer and media thinker Clary Shirky wrote a blog post imploring people to donate, David Carr featured the Amicos in a New York Times story, and donations picked up. A full three days before their Sept. 13 deadline, the Amicos had raised $40,000. (In the end, they netted $47,450.)

For Homicide Watch, Kickstarter was a last resort. The Amicos tried to get grant money. They tried to get existing Washington newsrooms to license their software. None of it worked. There are crowdfunding sites — like Spot.us and Newsfunders, which is still in development — that are dedicated solely to funding journalism projects. But Laura says Homicide Watch went with Kickstarter because it has name recognition that other sites lack. Already having a network of supporters in place — to donate, but also to help spread the word — was key to success in a fundraising campaign that was “a full-time job, nonstop for 28 days.”

“The initial days of the campaign, and actually the first initial hours, it was a lot of us and others reaching out to influential people we knew saying, ‘Hey can you promote this?'” Laura said. “Clay got Arianna Huffington to tweet it. It sat on the front of HuffPo for a couple of days. Finding ways to get people with influence involved, I think, was key for us. I feel just incredibly lucky that we had that network.”

Lesson No. 1: Before you start a Kickstarter campaign, you better have a long list of people to tell about it. Otherwise, unless you’re lucky enough to have Kickstarter put your project on its homepage, few will even know it exists.

Actually raising money is only part of the challenge with Kickstarter, which has to approve a project in the first place. The Amicos’ first Kickstarter campaign pitch last winter was rejected because the rewards they proposed — the special add-on that donors gets based on the amount they donate — weren’t good enough. (Update: Kickstarter’s Justin Kazmark emailed me after this article went up to say that the first proposal wasn’t rejected per se. “Someone from our team suggested they just give more thought to their rewards before launching,” he said.) This time around, awards varied from donors names being published in a “thank you” post ($10 or more) to getting the Homicide Watch team to guest-teach a class or lecture ($5,000 or more).

“Kickstarter is an odd fit for journalism in many ways,” Laura said. “The symptom of that to me is that rewards are so problematic. Public media does tote bags. Tote bags even have nothing to do with what you’re actually producing, which is the point of Kickstarter. It doesn’t have anything to do with the product we’re offering, necessarily.”

Kickstarter cofounder Yancey Strickler told me that journalists often struggle with figuring out what kinds of rewards to offer. “The No. 1 thing that a journalist has to offer is access,” he said. “You can offer access while not breaking any boundaries or crossing any lines that are drawn for journalists. You can offer access in the sense that you’re sharing maybe a diary about the experience of researching the story. If you’re speaking to an audience that cares about the story, that will be interesting.”

Journalists sometimes tend to worry about scooping themselves, revealing too much about a project and tipping off competition or the subject of an investigation. One way around that is to incorporate a time-delay into what you’re releasing. When political cartoonist Ted Rall used funds from a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2010 to go to Afghanistan, for example, he waited to release exclusive materials to donors. Strickler points to Rall as one of the poster boys for how journalists can make Kickstarter work for them.

Journalists sometimes tend to worry about scooping themselves, revealing too much about a project and tipping off competition or the subject of an investigation. One way around that is to incorporate a time-delay into what you’re releasing. When political cartoonist Ted Rall used funds from a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2010 to go to Afghanistan, for example, he waited to release exclusive materials to donors. Strickler points to Rall as one of the poster boys for how journalists can make Kickstarter work for them.

What Strickler didn’t mention was that Rall tried to fund another project with Kickstarter in May, and failed. “My Kickstarter book project is going down in flames,” he wrote in a May 15 blog post. He ended up raising $9,758 of the $40,000 he sought.

Tracking unsuccessful campaigns isn’t easy because Kickstarter makes them hard to find.

“There was controversy earlier this year when someone alleged that we were hiding failed projects,” Strickler said. “They were once browsable — well, they were never browsable, but you could find them in Google — but people were Googling their own names and they were seeing their failed Kickstarter project as the top result. Obviously that sucks, and it’s something that follows you around. Every time you apply for a job, it’s there. So we decided to take those things off of Google. The argument before was, ‘Why aren’t these things public because people could learn from them?’ The fact is, when you actually look at these projects, there’s not a lot to learn, because there aren’t huge differences between them and the ones that are successful.”

“My harshest critique of the Kickstarter model is that Internet culture is dorky and geeky and those people rule the Internet.”

So in terms of success or failure, how do journalism projects stack up against overall Kickstarter projects? (Keep in mind, Kickstarter considers journalism a subcategory of publishing — but photography and film are separate categories. Nonfiction is another subcategory of publishing, distinct from journalism.) Here’s the data the site provided:

Those numbers jibe with what University of Pennsylvania professor Ethan Mollick found when he scraped data from the site. Mollick says the journalism subcategory makes up 0.8 percent of overall Kickstarter projects — remember, that’s not including nonfiction, documentary film, or photography — and that journalism projects do “slightly worse” than projects overall. (Using Kickstarter’s numbers, journalism projects have received 0.6 percent of the total pledges since 2009.) Because of the small journalism sample size, cross-category comparisons are statistically fraught. But Mollick says he was able to draw some larger conclusions about what works and what doesn’t on Kickstarter.

A 30-day project, he says, is better than a 60-day project. (People tend to donate most heavily toward the beginning and end of campaigns anyway.) Campaigns with videos are consistently more successful than those without videos. Campaigns that are too big or too small don’t do well. (Mollick found 225 projects with goals below $100 and 25 with goals above $1 million. None were successful.)

“In general, smaller is better,” he told me. “The larger your goal, the worse you do. The general rule that I’ve been telling people is you want to set your goal at the amount you actually need because people who think they’re going to raise a lot more than their goal are wrong. The amount you raise, if you succeed, tends to be very close to the amount you ask for.”

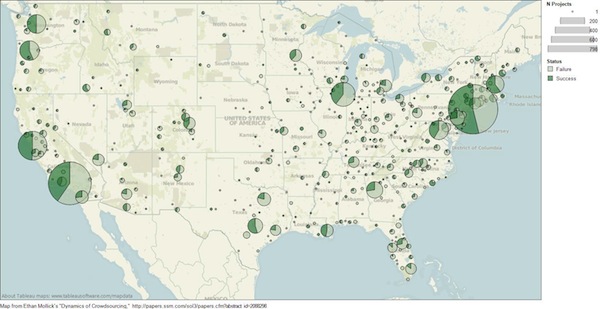

Mollick also mapped regional funding trends. Turns out Boston-based journalism projects have the highest success rate, and those in Los Angeles have the lowest. (It’s hard to know what to make of this, since people can donate from anywhere.) Here’s a look at how journalism projects alone have fared across the country, based on data Mollick collected over the summer. (The darker green indicates successfully funded projects):

And here’s Mollick’s map of success rates for journalism, nonfiction, and documentary film projects:

“As a way of funding, we know very little about it,” Mollick said. “A lot of people are pinning their hopes on this as a way to make up for the decline in media, the decline in arts, but nobody really knows that much about it. For me, this is a window into the success of individuals — what makes some people better at pitching things than others? What makes some areas more creatively successful? What kinds of projects gets funded? Who starts them? What are the antecedents of success and failure? The evidence is the more prepared you are the better. Preparation beats passion. Being passionate is less successful than being prepared.”

Here’s another tip: Don’t expect people to be as excited about your second Kickstarter campaign as they were about the first. That advice comes from Rall, the political cartoonist who used Kickstarter-raised funds for a trip to Afghanistan to report about “what has changed and how life is going for Afghans, especially those in the remote provinces in the southwest where Western reporters never venture.”

That was his first campaign, and he raised more than $25,000. (You can check out his cartoon blog from the trip here. Farrar, Straus & Giroux subsequently offered Rall a publishing deal and he’s set to release a book in 2013.)

Last spring, Rall took to Kickstarter for a second time, this time seeking $40,000 to produce a “self-help book for the leaders of the next U.S. revolution.” He didn’t even get a quarter of the way to his goal.

“Obviously, nobody really knows why one thing works and one thing doesn’t,” Rall told me. “There were two things that made the first project work as opposed to the second one. The first one is that it is the first one. The second time you get married, people don’t buy you as many presents. Another component I think is that with the first one, it was definitely a very populist idea. People are really interested in knowing what’s going on in Afghanistan. The second project, it was definitely, no doubt, extremely esoteric — gaming out what revolution would look like in America. You’d have to be a wonk or someone very interested in revolutionary politics to be behind it.”

Rall still thinks Kickstarter works but that its role in an industry desperately seeking long-term revenue solutions shouldn’t be overstated.

“I will confess to being a little bit skeptical about this format working to fill the gap left by the demise of print media, because it’s arbitrary,” Rall said. “You see really insipid, stupid projects. I don’t think it’s a problem with Kickstarter — Kickstarter does end up funding a lot of very worthwhile, very cool stuff — we have a bigger issue here, a bigger problem. It’s always about taste. The problem is that people’s taste is uneducated and unsophisticated. My harshest critique of the Kickstarter model is that Internet culture is dorky and geeky and those people rule the Internet. So if you’re trying to build a statue of RoboCop in Detroit, people get behind that…but anything serious is not likely to get done.” (Rall similary expressed his frustrations in a blog post and on YouTube.)

This may sound a bit like sour grapes from someone who successfully used Kickstarter to fund a serious reporting project, but Rall’s larger point is that success is contingent upon the whims of people’s tastes, which can make it hard to reverse engineer a campaign’s outcome. Another potential tipping point: Kickstarter’s decision whether to promote a given project. The site put Rall’s first campaign on its homepage, but he wasn’t so lucky the second time.

“I do think it’s kind of amazing that at a time when the economy is terrible and people don’t have a lot of disposable income, there’s such an incredible hunger for this kind of creativity,” Rall said. “It’s a wakeup call to producers and publishers. They’re really failing to service they’re viewers. To me, if I were an editor looking at Kickstarter, I’d say these are my readers who bypass me.”

Some of the other high-profile journalism projects that have successfully funded Kickstarter projects include the radio show 99% Invisible, which asked for $42,000 and got $170,447, and long-form journalism project Narratively, which brought in $53,740 in a $50,000 campaign. After several members of the editorial team at GOOD Magazine were fired, they — along with two who quit — launched Tomorrow Magazine on Kickstarter. They asked for $15,000 and got $45,452. Kickstarter’s Strickler says no major media company has launched a Kickstarter campaign, he suspects because passing the hat might spook stock holders of publicly traded companies.

Blank on Blank, which produces new stories from never-before-aired interview tape, raised $11,337 after its 30-day $10,000 campaign in July. Founder David Gerlach told me the money’s “obviously great” but it’s not why he launched a Kickstarter project in the first place. “We did it as more of a marketing tool and a call for content than for money,” Gerlach said. “Kickstarter has become such a creative force, I thought it was the perfect place for us to go to say ‘We’re here.'”

Strickler calls the site a “creative ecosystem” first and foremost, which is also why he says the team at Kickstarter hasn’t focused more on figuring out metrics for success. Crowdfunding just happens to be the mechanism used by what he sees as a community of artists and those willing to support their work. “Projects live or die based on the creator,” he says, and there aren’t “clear, universal attributes” indicating success or failure.

“What I find interesting and distinguishing about the best projects is it really comes down to a sense of character that they have,” Strickler said. “You watch these videos and there’s some very human attribute where you can sense someone’s sincerity: ‘This person’s full of shit, but this person really cares.’ You can just tell. I don’t know how you chart that. But to me that’s the difference. Kickstarter is so human, and that dictates how you feel about it.”