If I had only one short sentence to describe it, I’d say that journalism is factual reports of current events. At least, that’s what I used to say, and I think it’s what most people imagine journalism is. But reports of events have been a shrinking part of American journalism for more than 100 years, as stories have shifted from facts to interpretation.

Interpretation: analysis, explanation, context, or “in-depth” reporting. Journalists are increasingly in the business of supplying meaning and narrative. It no longer makes sense to say that the press only publishes facts.

New research shows this change very clearly. In 1955, stories about events outnumbered other types of front page stories nearly 9 to 1. Now, about half of all stories are something else: a report that tries to explain why, not just what.

This chart is from a paper by Katharine Fink and Michael Schudson of Columbia University, which calls these types of stories “contextual journalism.” (The paper includes an extensive and readable history of all sorts of changes in journalism in the 20th century; recommended for news nerds.) The authors sampled front-page articles from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in five different years from 1955 to 2003, and handcoded each of 1,891 stories into one of four categories:

Investigative journalism picks up after the 1960s but is still only a small percentage of all front-page stories. Meanwhile, contextual journalism increases from under 10 percent to nearly half of all articles. The loser is classic “straight” news: event-centered, inverted-pyramid, who-what-when-how-but-not-so-much-why stories, which have become steadily less popular. All this in the decades before the modern Internet. In fact, previous work showed that the transition away from events began at the dawn of the 20th century.

Investigative journalism may have pride of place within the mythology of American news, but that’s not really what journalists have been up to, by and large. Instead, newspaper journalists have been producing ever more of a kind a work that is so little discussed it doesn’t really have a name. Fink and Schudson write:

…there is no standard terminology for this kind of journalism. It has been called interpretative reporting, depth reporting, long-form journalism, explanatory reporting, and analytical reporting. In his extensive interviewing of Washington journalists in the late 1970s, Stephen Hess called it ‘social science journalism’, a mode of reporting with ‘the accent on greater interpretation’ and a clear intention of focusing on causes, not on events as such. Although this category is, in quantitative terms, easily the most important change in reporting in the past half century, it is a form of journalism with no settled name and no hallowed, or even standardized, place in journalism’s understanding of its own recent past.

From this historical look, fast forward to the web era. The last several years have seen a broad conversation about “context” in news. From Matt Thompson’s key observation that a series of chronological updates don’t really inform, to Studio 20’s Explainer project, to a whole series of experiments and speculations around story form, context has been a hot topic for those trying to rethink Internet-era journalism.

I believe this type of contextual journalism is important, and I hope we will get better at understanding and teaching it. The Internet has solved the basic distribution of event-based facts in a variety of ways; no one needs a news organization to know what the White House is saying when all press briefings are posted on YouTube. What we do need is someone to tell us what it means. In other words, journalism must move up the information food chain — as, in fact, it has steadily been doing for five decades!

Why does this type of journalism not even have a name?

I have a suspicion. I think part of the problem is the professional code of “objectivity.” This a value system for journalism that has many parts: truth seeking, neutrality, ethics, credibility. But all of these things are different when the journalist’s job moves from describing events to creating interpretations.

There are usually multiple plausible ways to interpret any event, so what are our standards for saying which interpretations are right? Journalism has a long, sorry history of professional pundits whose analyses of politics and economics turn out to be no better than guessing. In concrete fields such as election forecasting, it may later be obvious who was right. In other cases, there may not be a “right” answer in the traditional, positivist sense of science. These are the classic problems of framing: Is a 0.3 percent drop in unemployment “small” or is it “better than expected”? True neutrality becomes impossible in such cases, because if something has been politicized, you’re going to piss someone off no matter how you interpret it. (See also: hostile media effect.) There may not be an objectively correct or currently knowable meaning for any particular set of factual events, but that won’t stop the fighting over the narrative.

This seems to be a tricky place for truth in journalism. Much easier to say that there are objective facts, knowably correct facts, and that that is all journalism reports. The messy complexity of providing real narratives in a real world is much less authoritative ground. Nonetheless, we all crave interpretation along with our facts. Explanation and analysis and storytelling have become prevalent in practice. We as audiences continue to demand certain types of experts, even when we can’t tell if what they’re saying is any good. We demand reasons why, even if there can be no singular truth. We demand narrative.

What this latest research says to me is that journalism has added interpretation to its core practice, but we’re not really talking about it. The profession still operates with a “just the facts, ma’am” disclaimer that no longer describes what it actually does. Perhaps this is part of why media credibility has been falling for decades.

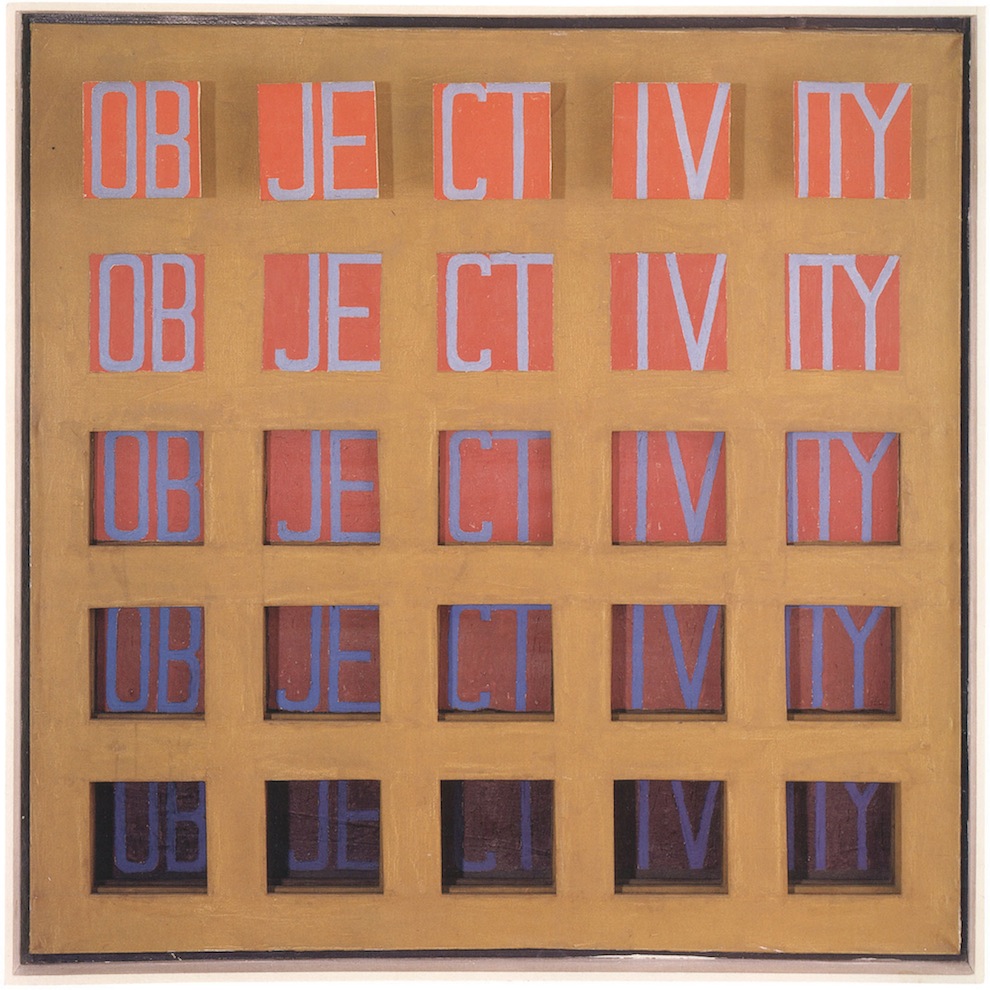

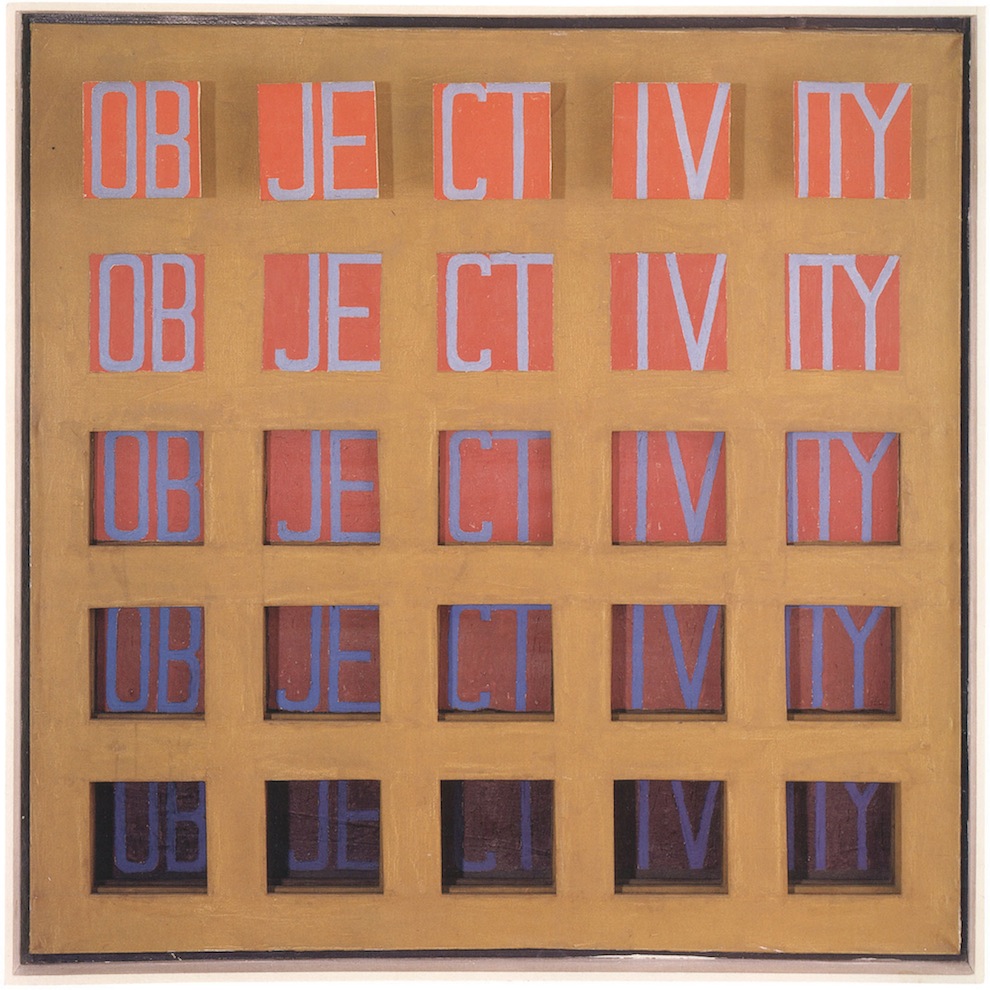

Photo of Sol LeWitt’s “Objectivity” (1962) via AP/National Gallery of Art.