“There is no statistical evidence anywhere that print circulations are declining because of the Internet. I’ve said this many times, and everybody tells me I’m talking complete rubbish,” says Jim Chisholm. “Circulations in the U.S.A. were declining long before anyone invented the word ‘WWW’…The cause of decline in analog consumption is more to do with changes in society than it is to do with the emergence of the Internet.”

That argument — that the decline of newspapers’ fortunes has roots much deeper than the proliferation of screens in our lives — may go against the flow, but Chisholm, a Scottish newspaper consultant, believes it’s important to acknowledge it if newspapers are going to thrive. He presented his ideas at this year’s WAN-IFRA newspaper congress in Bangkok (which Frédéric Filloux deftly summarized), making a case that online content is, at this point, no replacement for print when it comes to reader engagement — and, therefore, advertising revenue.

How newspapers are faring online depends on how you look at the numbers, which Chisholm draws from comScore and Nielsen. On one hand, newspapers are among the most popular destinations for Internet users in the United States — 61.5 percent of Americans with an Internet connection visited a newspaper’s website in May, for instance.

But that same data says that Americans often don’t go much further than a newspaper’s homepage and don’t spend much time actually reading its content. Newspapers represented just 1.5 percent of pageviews, 7.9 percent of total visits, and 1.7 percent of the total time that Americans spent online in May, Chisholm says.

“The central point of my argument is that newspapers are reaching out to people very successfully, but the reason they are failing commercially, is because people are not visiting newspapers [online] in any great number,” Chisholm said. “Whereas with a printed newspaper, you tend to read it for about 25, 30 minutes, the digital newspaper you tend to read for only five…The net result of this is, when you compare print and digital consumption — by that I mean times visited, number of pages visited, time spent with each page — the consumption level worldwide is about five percent that of print.”

(Longtime Nieman Lab readers may remember Martin Langeveld making a similar argument back in 2009 — that print engagement with newspapers was so much more intense than its online equivalent that print was still wildly dominant in how people engaged with newspaper content.)

Chisholm’s argument is that this is a cultural trend — that as people fill their days with recreational activities on- and offline, there is little time left to read the news of the day, in any format. And what time is spent reading newspapers is geared toward only the news that is relevant to the individual — as Ethan Zuckerman writes in his new book Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection, “Our challenge is not access to information; it is the challenge of paying attention. That challenge is made all the more difficult by our deeply ingrained tendency to pay disproportionate attention to phenomena that unfold nearby and directly affect ourselves, our friends, and our families.”

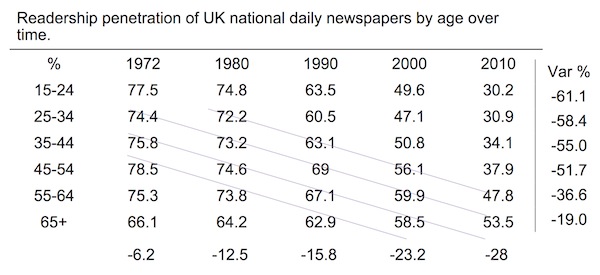

Here’s one chart from his Bangkok presentation, showing how reading habits by age cohort have shifted over time in the U.K. for national newspapers. In the ’70s and ’80s, young people were actually the age group most likely to be reading a paper. That trend began to shift by 1990, and by 2000 — a time when the Internet was still quite young as a mass consumer medium — young people were already giving up the habit.

“This is audience-consumer behavior,” Chisholm said. “The problem is that newspapers compete as much with the golf course and the restaurant, and people’s lifestyles, as they do with digital media. I think the nature of news is changing. Today news is far less serious and far more celebrity-based, and Twitter and Facebook feed themselves into that in a very precise way…The biggest cause of decline in circulation is purchase frequency. People are still reading and buying newspapers from time to time, but they buy them less often, and that’s a challenge.”

So if people — particularly young people, he says — are growing less engaged with news, as Chisholm argues, what’s the right path of investment for newspapers? He’s criticized newspapers for shifting too much of its investments toward digital — not because print will last forever, but because allowing the print product to decline has accelerated circulation losses — which have in turn meant there’s less revenue available to invest in digital. (Most newspapers still generate only around 15 percent of their revenue from their digital products.)

In a piece for News & Tech last fall, he argued the place to push is tablets:

I rarely say this, but here goes: Tablets are the future. Indeed — and I sense some of you are about to stretch out for your defibrillator — I could see a point where it is more cost/benefit effective to give a subscriber a free, customized tablet, loaded with their newspaper as a default, rather than spend money on paper and distribution.

Tablets users are more likely to engage with ads, and seem to be one of the few digital solutions that could rival print ad consumption, Chisholm believes. “What you’re basically paying for is bang for buck, isn’t it? And you still get more bangs in print, so money remains in print. And the challenge for newspapers is to get people to visit more often, to visit more content, and spend more time with it,” he said. “There’s a direct correlation between the level of consumption and the level of advertising revenue generated.” Tablets can help there, he argues, in part because they offer benefits similar to both print and digital experiences — you can read a package of content from front to back or you can surf around, and new navigation concepts can encourage deeper engagement. More and better marketing can help, too.

In 2009, Chisholm worked with the Newspaper Association of America to issue a forecast on what the media industry will look like ten years into the future. “Things have turned out worse than I predicted,” he says now. “The point of inflection, as I called it, where Internet revenues grow faster than [print] advertising revenues decline, is taking longer than I expected. But I still think that point will come.”

Photo by Mike Bailey-Gates used under a Creative Commons license.