The transition from summer to fall means students are returning to campus at journalism programs all around the country. What they do there will have a lasting effect on their careers and the future of the industry. But should they be following the example of a doctor or an entrepreneur in their studies?

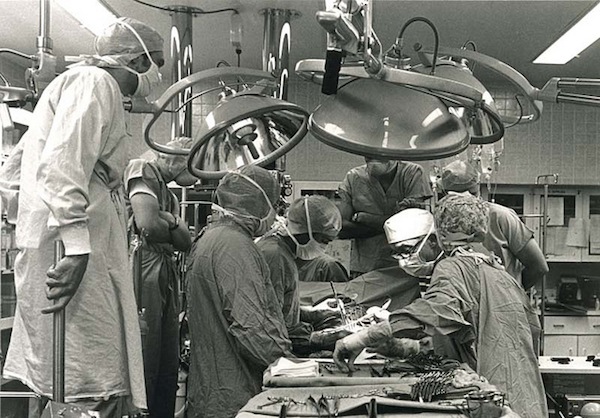

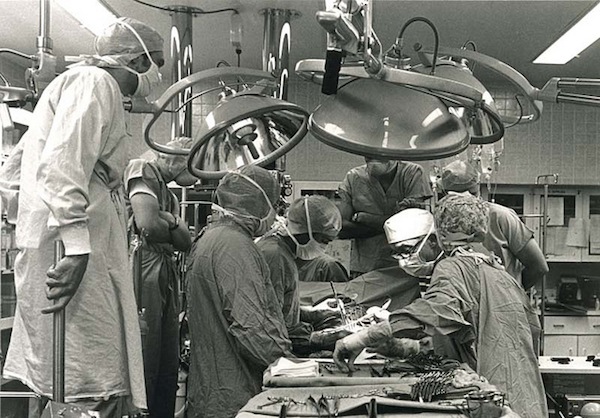

In recent years, the idea of adapting journalism education into a model resembling the one employed by teaching hospitals has become popular. Some see the Sacred Heart model as the way of offering real-world reporting experience to students while responding to the information needs of communities.

But not everyone agrees. Researchers David Ryfe and Donica Mensing of the University of Nevada’s Reynolds School of Journalism challenge the idea of the “teaching hospital” route in a paper that examines the assumptions behind the model and how it addresses the transformation taking place in media.

“We’re trying to figure out what our students need to know today like all j-schools are,” Ryfe told me. “We’re in a strange situation where much of what we’ve been teaching the last 100 years or so may not be helpful to our students going forward. The problem is we don’t know what part isn’t helpful.”

The paper, “Blueprint for Change: From the Teaching Hospital to the Entrepreneurial Model of Journalism Education,”(available here) argues that rather than giving students real-world experience, the teaching hospital model could be reinforcing practices and ideals that are harmful to the industry. Ryfe and Mensing write:

Our argument is that this model, if practiced by many journalism schools, could actually slow the response to change. The metaphor implies that journalism is a settled profession with clear boundaries that needs only to be practiced more rigorously, instead of a field with its most fundamental premises unraveling. Rather than creating conditions for students to help re-think journalistic practices, the teaching hospital model reinforces the conviction that content delivery is the primary purpose of journalism. Put simply, it makes it hard for students to think differently.

The teaching hospital model has been advanced by journalism leaders like Nicholas Lemann, outgoing dean of Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism, and Eric Newton, senior advisor at the Knight Foundation. (Newton proposed adopting the model in a piece for us last year; it’s worth reading to see the pro side of this argument.) Last fall, Knight joined five other foundations to pen a letter asking university administrators to embrace the model: j-schools providing a setting for experience and for practitioners (former or current journalists) to teach in a manner similar to doctors and med students.

But the teaching hospital metaphor doesn’t account for the pace of change happening in journalism, Ryfe and Mensing argue. While scientific breakthroughs have continually advanced medicine, they haven’t resulted in the kind of havoc at the core of the industry that news media has experienced. At a teaching hospital, students are instructed on what is known — how to diagnose heart disease, methods to treat blood disorders, or how to play in an air band. But in journalism, there’s a lot of uncertainty and change on every level, Mensing said — if the role of a teaching hospital is to prepare students by rote instruction to take their place in the field, all that results in is more journalists unprepared for changes taking place in the industry, she said.

Learning the practice of newsgathering from current or former journalists can also mean socializing students in the habits of their instructors, Ryfe said. “We put them in the place of a 45-year-old journalist today. They go in at 22 and are already cynical and lost,” Ryfe said. “They’re almost nostalgic for something they haven’t experienced.”

The model is intended to focus journalism education on experiential learning while supplying news to the local community. But by adopting the medical profession as its spiritual guide, journalists may also be fluffing up their sense of self-worth, Mensing and Ryfe write. Seeing parallels between hospitals and newsrooms, and the goals of treating patients (or the public), can be attractive to journalists while the industry weathers disruption. “The teaching hospital model is building on that idea deeply ingrained in journalism that it would like to be a profession in the way lawyers are or doctors are,” Ryfe said.

Instead of following the path of med schools, Ryfe and Mensing argue journalism education should take a more entrepreneurial approach to prepare students for the future:

…one clear value of entrepreneurship is that of enterprise, and enterprise is a value everyone connected with journalism education can appreciate. Faculty and employees alike laud journalism students who are enterprising and creative, who are passionate about their work and willing to put the boots on the ground to see their work realized in myriad ways.

Some of the programs the paper highlights for taking an entrepreneurial approach include the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism and the Knight Center for Digital Media Entrepreneurship at Arizona State. Entrepreneurship, Mensing said, is about invention and change, which can be manifested in various ways inside a j-school. Critical theory or introduction courses allow students to look at the role journalism plays in society today and the various forms it takes on. For skills training, Mensing and Ryfe suggest courses that go beyond traditional reporting and editing to programming and data visualization. But the most important part of the entrepreneurial model, they say, is that it allows for flexibility in coursework and provides students with a framework to adapt to new methods of production or forms of communication.

Ryfe said most journalism educators experience the futility of trying to teach students how to use one set of tools for news, only to have them eclipsed by something newer. The important thing for educators is to teach students how to assess the tools they have available, how to learn independently, how to understand their audience, and how to measure success. “We have to put students out in the world,” he said. “We don’t have time to wait for journalism to become settled again.”

If Ryfe and Mensing have an overarching argument, it’s that journalism and journalism education aren’t settled, which is why picking metaphors can be both useful and troublesome. The teaching hospital model may very well work for some institutions, Mensing said. But the universe of j-schools holds programs of varying sizes, each of which has to find the teaching method that fits their faculty and students, she said. The future of journalism education may indeed be specialization, but not just on the part of students — individual journalism programs will also have to hone their curricula into differentiated approaches.

“Over time, journalism schools go down certain paths and stake their claim in particular forms of journalism, just like in other industries,” Mensing said. “We may no longer see all-purpose schools for everyone.”

Image from the Stanford Medical History Center used under a Creative Commons license.