Editor’s Note: The Nieman Foundation turns 75 years old this year, and our longevity has helped us to accumulate one of the most thorough collections of books about the last century of journalism. We at Nieman Lab are taking our annual late-summer break — expect limited posting between now and August 19 — but we thought we’d leave you readers with some interesting excerpts from our collection.

These books about journalism might be decades old, but in a lot of cases, they’re dealing with the same issues journalists are today: how to sustain a news organization, how to remain relevant, and how a vigorous press can help a democracy. This is Summer Reading 2013.

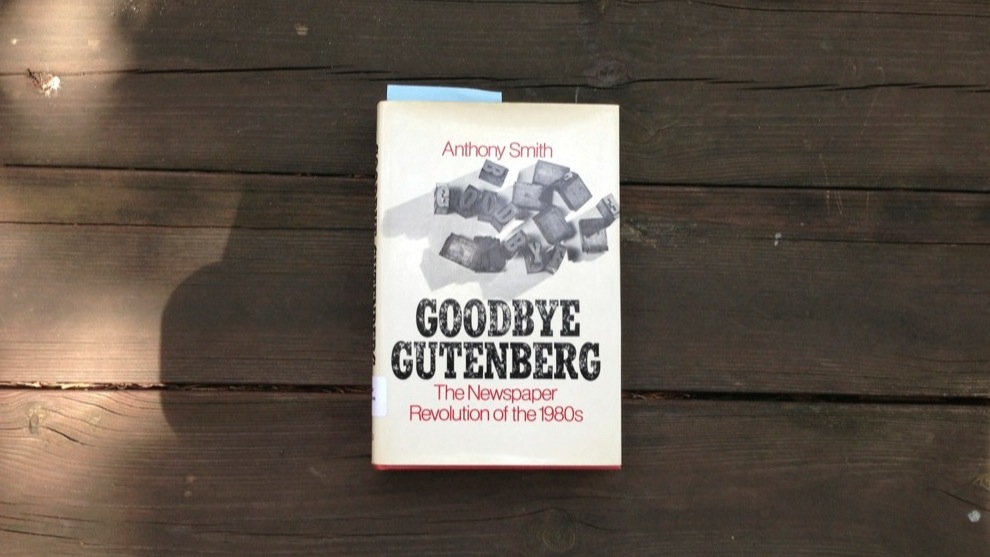

Smith’s Goodbye Gutenberg: The Newspaper Revolution of the 1980s is a look at a healthy industry enjoying the quiet before the storm. That’s not the reader having the benefit of hindsight, but Smith laying out the case that technology, already transforming the production and delivery of printed papers, will cause major changes to journalism.

Smith’s view of the future of media is shaped through his background in television. He proposes an information world of tomorrow that revolves around a screen: the TV. Smith was a producer for the BBC during the 1960s, later moving on to become director of the British Film Institute. He also served as president of Magdalen College, Oxford.

Information delivered directly to the home is coming, he says. And while that may not amount to much during the Reagan administration, “this means that the decade of the nineties is going to be one in which the traditional newspaper may face decline, extinction, or at least complete internal self-reappraisal.”

In Goodbye Gutenberg, Smith spends much of his time taking stock of how computers have changed the inner workings of newspapers, from subscriber billing and delivery routes to reporting and editing in the newsroom. But he also stops to consider what relationship electronic media will have with traditional media, how these two sides will compete, and what it will mean to be a new breed of publisher. He was decades ahead of the debates on aggregation, copyright, and the role of non-institutional publishing.

We have been examining in some detail the role of the computer inside the existing newspaper industry and have seen something of the impact it exercises over employment, industrial structure, and profits. The transference of information storage to computer is, however, also creating a new range of external media, so to speak, new devices to bring reading materials into the home or office. As a result, a vast range of perplexing issues is opening up. Should we consider these new media merely as extensions of the newspaper form? Are they simply new publishers (and old) moving into a new form of competition with the newspaper? Are they a threat to the newspaper or to any other information medium? Are they news media at all, or rather some new kind of reference medium? Will they remain forever locked into specialist forms of information, thereby stripping the newspaper of some range of material but leaving the bulk of information paper-bound as in the last several centuries?

There are other questions to be faced as well. Who is responsible for these new media that all depend upon telecommunications carriers that are either designated as common carriers or as nationalized monopolies? Is it possible, therefore, to transfer to devices that send information direct to the home on video screens the whole panopoly of ethical and regulatory paraphernalia — the rights of reporters, editors and publishers; doctrines of objectivity; editorial freedom; news values?

Are all these terms now to become part of some antiquated information theology, displaced by a new set of ethics emerging from a rearranged set of tensions between governments, providers of information, carriers, and readers? What will happen to libel laws, codes of journalistic conduct, contempt rules, and copyright protection in a medium that through its sheer profusion of material is unpoliceable, as ungovernable technically as the telephone conversations of an entire society?