What a difference a year makes in America’s national newspaper war.

When Rupert Murdoch bought the Journal and its parent Dow Jones six years ago, he declared that war, aiming to blur the historic line between a business newspaper and a general interest one. The declaration was pure Rupert: part real animus, part envy, part bluff, and wholly aimed at winner-take-all. Even as the deep recession wounded all publishers, Murdoch invested in the conflict, establishing The Wall Street Journal as a pioneer in news video, tablet innovation, and global growth, while also investing in old-fashioned reporting resources, launching expansions both in general news and in coverage of New York City. His moves on offense contrasted with the strategic retreats of the Times. The proud company was forced to sell its new headquarters space, take on onerous loans, and live perilously on the edge.

For much of the past half decade of hand-to-hand combat, the Times appeared uneasy in its footing. Through tough times, it managed to hold together its core asset — the 1,100-or-so–strong newsroom. But for much of 2012, the eight-month search for a new CEO emphasized the Times’ double vacuum of leadership and strategy. The media’s whispering classes conjectured that the Times was taking so long to find a CEO because the choice could be the one that would make or break the Times’ ability to survive as a standalone, Sulzberger-family–directed institution. Then, enter new CEO Mark Thompson, immediately dogged by various BBC messes, as he worked to establish credibility for himself on this side of the Atlantic.

Today, the tables have turned a bit. At the Times, the reader revenue strategy — exemplified by its digital paywall — has offered a greater sense of stability, a modicum of hope, and a budding confidence. It has completed a multi-year strategy to place all its chips on the flagship New York Times brand, selling off The Boston Globe and rebranding the storied International Herald Tribune as the International New York Times. Thompson looks like he has survived the North Atlantic winds of controversy. Though execution remains a big question, its areas of focus are the clearest they’ve been in a long time — innovating the second phase of reader revenue (“The newsonomics of The New York Times’ Paywalls 2.0”), finding new growth in digital advertising, and redoubling efforts and staffing in video and mobile. The Times organization is moving in a more unified direction than it had in previous years. Further, it is basking, even if just for a digital moment, in the glow of being the global pioneer in paid digital reader revenue models.

The year’s final financial performance (to be reported Feb. 6) will show a year similar to 2013, with maybe a little growth in revenue. It’s not out of the woods yet, but a clearing is visible.

The Journal is another story. At best reading, it’s been a year of reorganization, shuffling just about everything that could be shuffled, above and within the Journal’s reach. Its parent company spun off all its newspapers (and a couple of other balance sheet-improving ventures) into the new News Corp, complete with lyrical Murdoch-written logo, as the now-separate 21st Century Fox moves forward into the more profitable world of TV, film, and digital video. Lex Fenwick, the CEO of immediate WSJ parent Dow Jones, has brought Bloombergian B2B zeal to the remaking of the company.

Fenwick’s moves to radically rationalize and reshape Dow Jones B2B products have gained most of the attention, but a careful view shows that the same one-product, one-price strategy has fundamentally altered the Journal’s direction. Further, we’ve seen a profound exodus of top Wall Street Journal execs and much change in management overall — and limited new product development. Though fewer financial performance numbers are released about the Journal than the Times, a set of them affirms that the Journal’s assumed ascendancy in its head-to-head war with The New York Times is no longer true.

In previous years, I’d written much about the Journal’s innovations in video, mobile advertising, and other areas, more than I’d noted the Times’ product innovations. What happened in 2013 to turn the innovation tables? Though Dow Jones declined to comment on the company’s overall performance and strategic focus, I talked to numerous people in and around the war to get a sense of the wider newsonomics of the competition. Here we focus on their businesses, not their journalism — which continues to be distinguished in both shops. The success of those businesses, inevitably, will shape available newsroom resources for both companies in the years ahead.

Unexpectedly, this battle has between much more of a newspaper-to-newspaper competition. Six years ago, the Times still owned a variety of businesses from which it has now exited. Now it’s the Times alone. The corporate change in and around the Journal is more profound: While the Journal is part of a larger company, it is now a part of a newspaper company. Until the mid-2013 News Corp split, its performance could be subsidized by an Avatar blockbuster or healthy Fox News profits. Now it’s looked to as a profit center.

With News Corp’s London-based Times papers and New York Post being money losers, the Journal stands after the U.K. tabloid Sun (the best-selling paper in Britain) and its Australian newspapers in financial performance. Though new News Corp CEO Robert Thomson inherited a comfortable $2 billion cash cushion and no debt (in contrast to the planned Tribune spinoff), the cratering of the print ad business means that News Corp shares the financial pressures of its peers. The Journal must begin to stand on its own.

With that landscape in mind, let’s look at where the Journal now stands, in its management, its business performance, and its product innovation.

Fenwick took command of Dow Jones two years ago. Long-time Murdoch loyalist Les Hinton stepped aside, as the collateral damage of Murdoch’s U.K. Hackgate threatened to impact the Journal.

Fenwick seemed like an odd choice at the time. A veteran business-to-business executive, he brought the legacy of his long-time Bloomberg tenure to what had long been mainly a business-to-consumer company. Though Bloomberg’s B2B terminal-based model has been wildly successful, its multiple attempts to grow consumer businesses in TV, radio, and magazines have far less so.

Public attention on Fenwick has focused on two things. One is his management style. Fenwick is universally described as a man who likes to be the decider, a top-down exec in an age where at least the hint of collaboration is nearly universally espoused. Secondly, the information world has been astounded at his remaking of the B2B side of Dow Jones.

Launched after lots of internal integration at year’s end, DJX has become Dow Jones’ Bloomberg. It’s one product, largely at one price, bringing together its Factiva enterprise information services, the Dow Jones Newswires, and much more. The early reaction to the higher pricing (with some customers being asked to pay three times or more what they previously did) and to the lack of separate product choice has been noteworthy. Cancellations have been reported, but it’s too early to know the overall business impact of the major change.

What’s important for Journal watchers to know is that the same single-product, single-price strategy now being tested in the B2B marketplace has been applied to the Journal.

As the application became clear, the exodus began. The Journal has seen dozens of managers leave. Alumni talk about the exodus of summer 2012 and summer 2013. Within six months of Fenwick’s arrival in February 2012, the departures had begun, concentrated early on in and around the Factiva business. Some were forced; many were voluntary. The summer timing wasn’t coincidental: News Corp’s fiscal year ends June 30, and annual bonuses are paid in August. Consequently, it is the last 18 months of the Journal that have seen the greatest change.

Across the Journal, top management change has been sweeping. A very partial list of the departed:

All but Bowen — who now heads the challenged-but-cash-flow-vital digital business for News Corp’s Australian papers — left News Corp.

Why did they go? While Fenwick’s management style is part of it, the reasons go directly to the nature of what they were able to do to move the Journal’s business forward. As Fenwick moved toward single-product, single-price, the execs found:

Some weighed a personal strategy of waiting out the new regime. Most decided that even if top management were to change again, the unwinding of this single-product, single-price change would take a couple of painful years to happen.

The shock of the change — close to a 180-degree reversal — permeated all parts of the Journal’s consumer operation. It’s meant that the Journal — which put its model-breaking WSJ Live on more than two dozen non-WSJ video platforms (“The newsonomics of WSJ Live”) and did an early test with Pulse to determine the pros and cons of third-party distribution — cut back on its partnership and third-party platform testing. While the Times and the Financial Times are testing subscriber-authenticated reading on Flipboard, the Journal is absent.

The 2011 “WSJ Everywhere” strategy seemed an artifact of the past. Many of the business partnership plans and tests — all designed to pour new would-be paying customers into the top end of the customer flow via sampling — ebbed away. The issue: If you don’t throw out more fishing lures, through introductory pricing and wider sampling across platforms, paid subscriptions inevitably will flatten — which they have.

Further, the strategic change meant that new segmented, separately priced digital news products, like CFO Journal and CIO Journal, would be folded into the single subscriber proposition. Ironically, that comes at a time when separate niche products like Politico Pro is the new industry model — at the arch-foe Times too, where executives plan to test three such products in the spring.

That’s not to say that the Fenwick pricing philosophy doesn’t get credit. Even his critics say he has rationalized pricing that was too loose. The problem, they say, is that in swinging the pendulum over to stronger pricing, he hasn’t allowed that cheaper, introductory-offer sampling that the business today requires.

Among many of the exec replacements is a common career stop: Bloomberg. For instance, Trevor Fellows, who replaced ad leader Michael Rooney, is one of the many Bloomberg vets to have replaced the old guard. Beyond the question of clubbiness is that B2B background and how well it applies to the Journal’s consumer business.

To be clear, Fenwick had done with the B2B business what he was hired to do. Robert Thomson had longed talked about the B2P (professional) market, and how a company with Dow Jones’ vast resources should more smartly serve it. He’d been frustrated about the pace of that rethinking and reorganization. Thus he had a strong hand in selecting Fenwick. The goal: Make more out of the B2B businesses that may have contributed only about 30 percent of Dow Jones’ revenues — but a higher proportion of its profit.

The consumer impact of the Fenwick appointment may have been unanticipated.

When Robert Thomson leapt from his position as top editor of the Journal to CEO of the new split-off News Corp, the balance of power at the Journal shifted. Though Thomson had been the editor in title, he wielded much wider business influence. His successor, Gerry Baker, is much more a traditional newsroom leader. The business savvy that Thomson had brought to his job is no longer in place to balance Fenwick’s B2B proclivities, as the new CEO faces the big task of managing the new three-continent News Corp, the largest news company by revenues globally.

The Journal and Dow Jones financial performance is somewhere in the middle of the new News Corp pack. News Corp doesn’t break out the results of its individual companies. Overall, the company’s first quarterly report as a spin-off, issued in November, was subpar, down 5 percent in EBITDA and 4.3 percent in adjusted revenues.

Its majority News and Information segment was worse, off 6 percent in adjusted revenues year over over year. We do know that circulation revenues were down 6 percent overall at Dow Jones for the last quarter, or $11 million, though we attribute that decline to the company’s struggling B2B sales, not its Journal print and digital subscriptions.

Advertising still represents a majority of revenues for the Journal, sources say, in the mid-50s percentagewise, with circulation in the mid-40s. That’s the inverse of the Times, which recently reported that 56 percent of its revenues now come from readers. Given that reader revenue is now growing as paywalls have gone up, and that print ads remain in sharp decline, majority reader revenue seems to be the preferable market position.

Sources say that the Journal failed to make its advertising budget for 2013. Like all dailies, it is struggling with print, likely with a low-to-mid single-digit decline and a mild drop in digital advertising as well. That performance would be quite similar to the Times.

We can estimate the Journal’s current profit in the 5-8 percent range.

If we measure Lex Fenwick’s application of single-product, single-price to Journal subscription pricing, we can see where he’s had success. The Journal has long lagged the Times in pricing, and even his critics credit him with rationalizing print and digital pricing. While that has meant less sampling, it’s also meant more immediate revenue, with double-digit price increases in print and digital. How much more circulation revenue we don’t know, nor do we know how it compares to the Times’ year-over-year increase of 4.8 percent there.

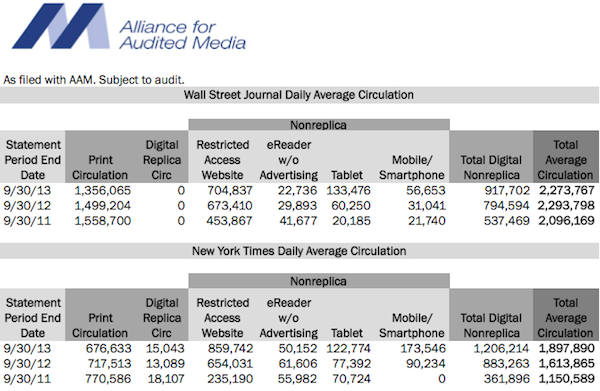

The overall readership numbers for the Journal, though, appear flat. Total average circulation, as measured by the Alliance for Audited Media (the industry’s successor to the Audit Bureau of Circulation) is down 1 percent, 2013 compared to 2012, as we can see in the chart below. The Times is up 15 percent, as we see below.

Both papers have lost print readers, of course, but the Journal lost more last year: 9.5 percent of its daily (six days a week) print circulation, compared to a 5.7 percent comparable weekday loss for the Times. Over the last two years, the Journal has lost 13 percent of print circulation; the Times has lost 12 percent.

Over the last year, the Times posted a 31 percent gain in paid digital products; the Journal was up 15 percent. Over the last two, the Times posted a 265 percent gain in paid digital products; the Journal was up 55 percent. (Observers may note that The New York Times’ “total non-replica” number through September 2013 — 1,206,214 — is substantially higher than the paid digital-only subscriptions it announced at about the same time, 727,000. That’s because the AAM number counts digital usage as well as individual paid subscriptions. Constructively, that’s a double or triple accounting of some paid customers, a metric whose value is uncertain. For our purposes, the AAM numbers, though, offer apples-to-apples comparison between the Journal and the Times.)

Consequently, in all the available public reader data, the Times is faring better than the Journal of late.

To be fair, the Journal was a turn-of-the-century pioneer in paid digital strategy, and one might imagine a plateau would come given that 10-year lead. Acknowledging that, the questions become: What has the Journal recently done to build on that lead? And how come it let its foe catch up?

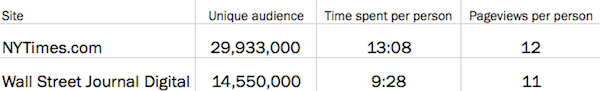

In digital traffic, October Nielsen data below shows the Times with far greater reach than the Journal in their home country. Its U.S.-based audience is more than double the Journal’s. The Times manages 36 percent more time per person than the Journal and a page more per month, a 9 percent advantage there. The Times’ new redesign, launched Wednesday, is intended to further that engagement lead, even as the Journal gets ready to launch its own digital redesigns later in the quarter.

Looking forward both on reader revenue and engagement, a critical question facing the Journal is whether to stick with its freemium model. That model, more commonly used in Europe, puts up a hard wall in front of many articles, especially the Journal’s unique stories, while allowing others to be freely read. Developed before the meter — which allows readers a free sampling of from 5 to 25 stories a month — the freemium model may be less flexible and consequently less successful in converting occasional readers into paying subscribers.

New product development is a reach for new subscribers and readers, for advertising — and for buzz. Both the Journal and the Times have learned from digital startups the value of launch announcements.

Both have emphasized video. Late last year, The New York Times Minute won lots of notice as an attempt to satisfy news customers with quick three-subject reports several times a day. Its year-earlier Snow Fall project had redefined integration of multimedia into traditional storytelling. The Journal’s WSJ WorldStream, a first-of-its-kind video blog, launched in mid 2012, but has received less attention. Alan Murray, the Journal’s then deputy managing editor and a key part of much of the pre-Fenwick consumer innovation, is another of the execs who’ve left, becoming head of the Pew Research Center in November 2012.

Video is a key battle area between the Journal, which once had a substantial lead, and the Times. Chris Cramer, named head of video last March, is one of those trying to restart the innovation engines at the Journal. A BBC/CNN veteran, he has been joined by Edward Roussel as head of product and Michael Rolnick as chief digital officer.

Cramer points to growth in the video business, citing:

Further, the December News Corp purchase of video aggregator Storyful should help video strategies — and indicates the potential of greater strategic alignment across News Corp news properties.

For all who’ve moved into new roles at the Journal, the tasks are straightforward and parallel the goals that Mark Thompson has set out at the Times. They are all around the familiar: more reader revenue, support of digital advertising, mobile expansion, video exploitation. That requires building on innovation, marketing it well, and being perceived as a leader. This is a game both about leading change — and grabbing attention for it. Here, too, the Times seems to have gained an edge on the Journal.

We’d have to believe that a comparison of the Journal’s and the Times’ recent trajectories would make Rupert cringe. He believed he had the Times on the ropes, and now he finds his prized Journal playing catch-up. at least in the game of media perception and in a number of key metrics. In trying to fix the B2B side of Dow Jones, the company looks like it took its eye off of the Times competition, allowing the Times to catch up after Murdoch and Robert Thomson had invested so much in the new Journal.

Thomson, himself, has got to be casting a more direct eye on the paper’s fortunes as Lex Fenwick enters his third year of reorganization with quite uncertain results in both B2B and B2C. We may see the News Corp culture — pick a top leader and give him room to make the changes he sees fit — tested strongly by the time 2015 comes around. Commanders have their place, but changing out the officer corps in mid-battle takes its toll.

In the Journal/Times faceoff, the competition is far from over — but the battle lines have changed.

Photo by Jonathan Seitz.