You know that old “If I had a nickel” saying? Well, if I had a nickel for every time I’ve heard the word “impact” — and impacting, impactful, impacted, high impact, etc. — since I joined the Center for Investigative Reporting as media impact analyst in July, I could go straight from my position as an ACLS public fellow to retirement. People want to talk about impact that much; I want to talk about impact that much. Impact might just be the holy grail of today’s media, both desired and elusive.

To have impact is a key goal of nonprofit journalism, as evidenced by recent articles from Poynter, American University’s Investigative Reporting Workshop, and ProPublica, to name a few. But the question remains: What is impact? The standard answer has been: “We’ll know it when we see it” — with the gold standard generally accepted to be large-scale changes, such as the adoption of a new law or a government investigation.

At CIR, we are proud that our reporting often results in structural, macro-level law or policy changes. But we know there are other types of real-world outcomes that are just as important. In fact, under certain circumstances, shifting the terms of a public debate or changing someone’s voting preferences is more likely to contribute to lasting social, political, and cultural shifts. What’s the value of a university student using facts from a CIR report about questionable travel spending by top school officials in a slam poetry video that went viral on YouTube? How can you be sure of the degree of impact of a story about an undercover FBI informant with ties to the Black Panthers when a high school teacher integrates it into his curriculum in Oakland? While it’s difficult to measure these types of outcomes and the relationships between them, we think that, ultimately, it will be worth the effort.

For nearly 10 years, nonprofit media makers and their funders have been debating issues surrounding impact, including definitions, measurement, and relevance. There are at least four strands of the conversation that have remained constant throughout and still need to be addressed: the need for standards, the relationship between audience engagement and impact, the significance of online analytics, and the difficulty of understanding how qualitative offline outcomes figure in to the long-term impact of media.

There is no standard definition of impact for nonprofit media. Each organization has its own understanding of what impact is. This lack of shared understanding is challenging for many reasons. For one, a lack of uniform definitions for the variables involved in the impact equation makes it impossible to share knowledge, measurement strategies, tools, or analytical expertise among organizations. The lack of standards also has resulted in miscommunication between funding partners and media organizations in which “impact” can mean different things for the various parties in a grant agreement.

The value of online and offline audience engagement is a question that both for-profit and not-for-profit media struggle with daily. What is the value of a comment online? Has someone’s opinion been changed if he or she “likes” a post on Facebook? What if he or she retweets an article? What’s the value of someone attending a live event or watching an entire documentary film?

In his white paper on impact, ProPublica president Richard Tofel writes: “A key factor in charting the effectiveness of explanatory journalism will be the engagement of readers.” He defines engagement as “the intensity of reaction to a story, the degree to which it is shared, the extent to which it provokes action or interaction.” But how do we capture this offline action — the changes in thinking and perception that may lead to change?Brian Abelson has put forth a metric of engagement for news apps, formulated using data from The New York Times that includes the number of events (engaging with elements on the page), multiplied by the number of shares and favorites.1 This is an important first step in creating a shared measure to compare engagement across newsrooms and websites. If this metric is calculated consistently, we will be able to tweak and hone the equation to more precisely reflect reality.

Quite simply, media producers have too many data points for online activity. For any given story, we know the number of pageviews, the number of unique visitors, where those visitors are, what time they read the news, how far they scroll down the page, how many elements they click within a page. In some cases, we even know visitors’ age, gender, and other personal information.

We also know how many likes, shares, and views a post gets on Facebook. We know who is tweeting with which handles, hashtags, and keywords. We spend considerable time and energy considering online analytics, attempting to divine meaning from numbers and graphs. But we still don’t understand what the data mean in relation to tangible impact.

While there is no clear definition of impact, it’s implicit that impact is real-world change. It should be obvious, then, that impact happens offline, out in the world.

Following this logic, it should be clear that we must look for impact offline. However, that’s not the case. Because offline activities are messy and irregular and require staff and time to track, they are cast aside as, at best, qualitative data and, at worst, anecdotes. But qualitative data is still data, and it’s as valuable as quantitative data if it is collected and analyzed using rigorous methods.

CIR is not alone in the quest to develop a clear conceptualization, or model, of impact that goes beyond changing laws. Our approach is distinctive in its transparency and our willingness to engage in a process of introspection, experimentation, and analysis to contribute to the body of knowledge around media impact.

CIR’s reporting has led to instances of real-world impact that often have been unforeseen. For example, Rick Edmonds of the Poynter Institute pointed out: “The recent Tampa Bay Times/Center for Investigative Reporting project identifying America’s Worst Charities is likely to result in tougher regulations in a number of states. But it should also motivate prospective donors to do a little due diligence on where the money goes before responding to a heart-tugging appeal.”How can we measure the increased due diligence of people contributing to charities as a result of our reporting? What is the relationship between the audience and regulators? CIR reporter Kendall Taggart addressed this challenge directly in the first pilot episode of Reveal, an investigative radio program produced by CIR and PRX, recounting how an elderly gentleman heard her on his local NPR station, got her contact information from his local library, and called CIR to ask for more information so he could be sure not to donate to bad charities.

Perhaps even more influential than individuals practicing more due diligence in their donations is the change in the debate about what constitutes a “bad” charity that has been raging in Nonprofit Quarterly and The Chronicle of Philanthropy, spurred by CIR’s reporting. If CIR’s work changes the understanding of what it means to be an upstanding charity within the most respected professional journals, long-term ripples of this impact will undoubtedly continue for many years and perhaps become ingrained as the new norm.

Not every story will result in legislative or policy change. But there are other types of outcomes. For example, CIR — in collaboration with the Investigative Reporting Program at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, Frontline, and Univision — produced a documentary called “Rape in the Fields” (“Violación de un Sueño” in Spanish), as well as an animated short and text article, exposing rape and harassment of female agricultural workers in the U.S. — all of which were distributed in English and Spanish. Because many of these women are not authorized to work in the U.S., it could be a political risk for an elected official to take up this issue of his or her own volition. Instead, the optimal outcome might be increased awareness within the involved communities; higher rates of reported rape or harassment; lower rates of assault, abuse, and violence; and use of the team’s reporting and CIR’s tool kits by advocacy organizations — things that are happening as a result of the reporting.

Did CIR and its partners consider the Rape in the Fields project unsuccessful because the California Assembly did not immediately take on the issue by writing legislation? Hardly. Instead, I would argue that this project has had impact in the strongest sense of the word: real-world change affecting the daily lives of hundreds — maybe thousands — of vulnerable women. In fact, eight months since the documentary first aired, there have been nearly 100 known organic, independent screenings, including for public officials. In response to a vast showing of public outrage and frustration, CIR in January facilitated a Solutions Summit in Sacramento. The daylong meeting brought together advocates for survivors of abuse, agricultural growers, legislative staffers, law enforcement officials, and others to have a conversation about possible solutions to this problem.

In light of these complexities, CIR has worked to clearly define and conceptualize impact in a way that is useful for our reporters, readers and supporters. CIR defines impact as a change in the status quo as a result of a direct intervention, be it a text article, documentary, or live event. Impact can be characterized by three types of outcomes: structural, macro events like changes in laws and policies; meso-level changes such as shifts in public debate; and micro-level changes, like alterations in individuals’ knowledge, beliefs, or behavior. Rather than any one type of outcome being the gold standard, we want to understand the relationship of convertibility among these outcomes. We are only beginning to think about how to quantify these interactions; this is not alchemy, but science — and maybe a little art. Like any science, there will be trial and error, fits and starts, and testing of hypotheses.

To propel this conversation, CIR has introduced CIR Dissection: Impact, bringing together media makers, funders, scholars and technologists to create a nationwide community of practice around media impact. The first two daylong events took place in the San Francisco Bay Area and Macon, Ga. Two additional Dissection gatherings are scheduled for April in New York and Washington. As a result of these meetings and our work at CIR, we will publish additional articles, including case studies, and host open discussions expanding upon our findings in the months to come. We welcome you to follow and join in the conversation.

Campolo, Alex, et al. “Sharing Influence: Understanding the influence of entertainment in online social networks,” Harmony Institute, July 22, 2013.

Chinn, Dana, et al. “Measuring the Online Impact of Your Information Project,” The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation/FSG Social Impact Advisors, May 31, 2011.

Clark, Jessica and Tracy Van Slyke. “5 needs and 5 tools for measuring media impact,” PBS MediaShift, May 11, 2010.

Edmonds, Rick. “Why it’s time to stop romanticizing & begin measuring investigative journalism’s impact,” Poynter, Aug. 20, 2013.Lewis, Charles and Hilary Niles. “The art, science and mystery of nonprofit news assessment,” Investigative Reporting Workshop at the American University School of Communication, July 10, 2013.

Linch, Greg. “Quantifying impact: A better metric for measuring journalism,” Jan. 14, 2012.

Stray, Jonathan. “Metrics, metrics everywhere: How do we measure the impact of journalism?,” Nieman Journalism Lab, Aug. 17, 2012.

Tofel, Richard J. “Non-Profit Journalism: Issues Around Impact,” ProPublica, February 2013.

Lindsay Green-Barber is the media impact analyst and ACLS public fellow at the Center for Investigative Reporting.

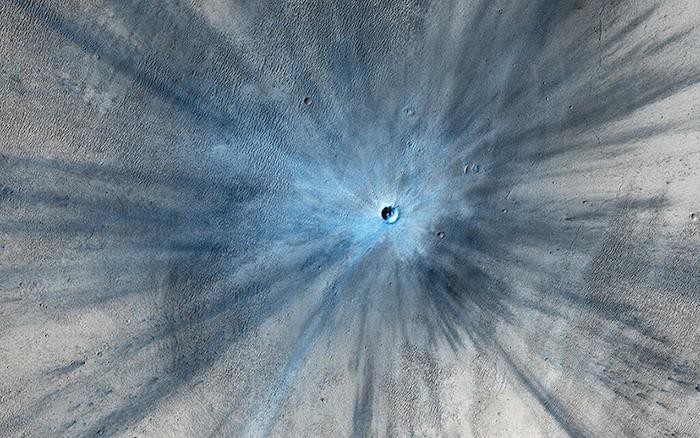

Photo of impact crater on Mars via NASA.