Native advertising is providing an ever-larger chunk of digital revenue for publishers these days. But despite (or perhaps because of) the money, lots of journalists are still squeamish about the topic. They worry that, at its core, native advertising is about tricking your reader into reading an ad and thinking its editorial content. Why would a reader who feels duped by a news brand ever want to return to it?

That’s the question that led Patrick Howe and Brady Teufel of Cal Poly to publish a research paper titled “Native Advertising and Digital Natives: The Effects of Age and Advertisement Format on News Website Credibility Judgments.” Howe, an AP journalist turned academic, said he heard experienced journalists worrying about the declining quality of advertising and the potential ethical dilemmas of native advertising.

“When I would go and talk to people, particularly journalists, almost everybody I would talk to — these are your New York Times-reading, NPR-listening crowd — almost everyone was convinced that it would be a disaster because people would feel tricked, and that they would take it out against the news organization,” he says. “That this is dirty pool, and news organizations shouldn’t do it.”

Howe devised a study of around 250 respondents, split between two age groups — half were between 18 and 25, the other half were over 45. He then wrote a survey that tried to determine whether the presence of native advertising affected how respondents viewed the credibility of a news source, comparing reactions of younger respondents to those of older respondents.

In the past, Howe says, the majority of studies in areas of information processing and credibility judgment have been conducted by people who have an interest in the advertising side. “The news in particular has been so bad about gathering information about their users online, and making good use of it, it always feels a generation behind in terms of doing what all the smart people on the Internet are doing,” he says.

Howe is more interested in directing his research toward practical, incremental findings and tools for publishers. He pointed to Talia Stroud’s work with the Engaging News Project as a unique example of applicable work being done in the field of news scholarship.“On the news side, we’ve got advertising doing applied work, and interesting work being done by economists at the 10,000-foot level,” he says. “Advertising is a huge part of the experience of consuming news, and yet there’s almost no research from news scholars into its effects.”

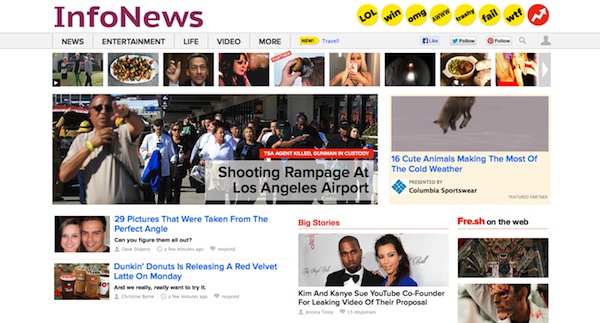

To construct the project, Howe collaborated with Teuful, whose expertise is in design, to construct two faux news site homepages. Using a mockup of a BuzzFeed page, Howe and Teufel exposed respondents to both native advertising (see the Columbia Sportswear ad at middle right):

and traditional display advertising (in the same slot):

Howe hypothesized that there’s be a substantial gap between how younger and older readers viewed the credibility of the site — but that’s not what happened. “I was so surprised by that result that I ended up going back in a panic and checking all my coding,” says Howe. “I really didn’t think that made any sense to me at first blush, and I’m not sure I have a handle on the explanation.”

In fact, people in both age groups felt more or less the same about the credibility of the two sites, regardless of what kind of advertising it displayed. Young people were slightly more likely to recognize native advertising as an ad, but what they saw did not influence their judgment of the site. Older viewers, meanwhile, tended to find the news site more credible no matter what, suggesting that older readers of digital media are more trusting and less judgmental than their younger counterparts.

“It could well be that the younger people knew this was a BuzzFeed ripoff, and the older people thought this was an anonymous news source,” Howe acknowledges. But he said qualitative responses about what contributed to the respondents opinions suggest, at least anecdotally, that older readers approach online media differently. (These responses were not published as part of the paper.)

“The older people were just a little nicer! This is purely my sense of things, but the younger people were just harsh. They would say things like ‘Garbage news.’ ‘Too busy.’ ‘Gossip format.’ ‘Looks flashy.’ Older people were more likely to say things like ‘images and headlines and the overall look.’ ‘The overall appearance.’ ‘They cited sources.’ ‘The content and design.” They were more big picture. Young people were more like, ‘That one thing sucked,'” Howe says.

Young people were also slightly more likely to recognize sponsored content as advertising, Howe found. “Younger people are more used to a world where advertising comes in all kinds of formats. They know there’s product placement in television shows and movies. They know the first returns on a Google search are [often] paid for. They know that there are sponsored tweets and Facebook ad posts. I think they’re more aware that advertising doesn’t always look like advertising.”

But there’s a catch-22 at the center of all this. A reader who doesn’t notice a native ad is an ad is also unlikely to notice the brand that’s paying for it. It’s that tension between normal editorial content and brand messaging that’s at the heart of the native advertising boom, and it’s unclear how sustainable that inflow of money can be as native becomes just another advertising format.

Of course, Howe and Teufel’s study is a small one that can’t be readily extrapolated to the entire online news business. For Howe, the most important next step is finding readers who do feel somehow violated by native advertising and studying their reactions. “I don’t know how to do that yet,” he says. Howe also says a public relations professional who buys native ads suggested he study advertisers instead of readers and try to parse their motivations. He’s also interested in finding a way to conduct a study that includes a more natural media discovery and consumption process — for example, using A/B testing to measure audience behaviors like engagement against different advertising types. There’s also interest in studying other native formats, like sponsored sections.

“We’ve got a huge problem that at least in the last few years has really threatened journalism in general, yet there really aren’t a lot of people trying to help in academia,” says Howe. “I want to be one of those people. I don’t necessarily want to serve the publishers, but I want to serve journalism.”