As we approach the middle of the 2010s, where do newspapers fit in the battle for America’s largest ad sector — digital? And how well are all those paywalls doing?

Two reports tumbled into the public sphere within a week of each other recently, and together, they help us answer both questions.

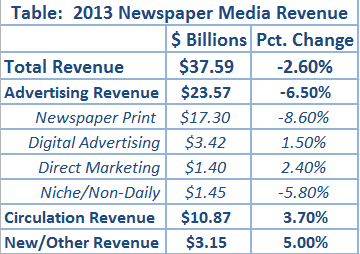

The numbers here show that the newspaper industry overall — a relative minority of leading-edge players aside — is trending the wrong way. Both digital ad revenue and reader revenue continue to grow, but both are less positive than they were a year ago.

Let’s start with the overall digital ad market.

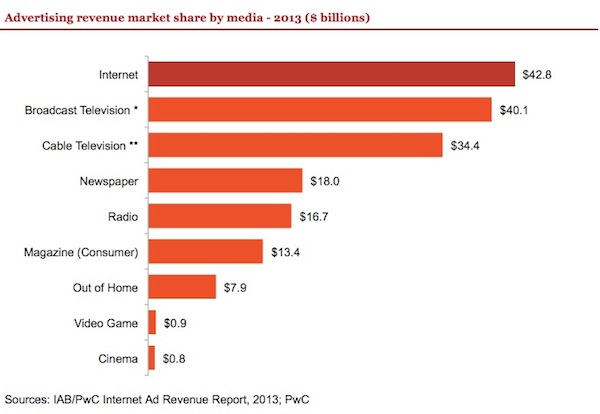

The Interactive Advertising Bureau’s 2013 full year report is its usual rosy self. Ten years ago, IAB had to explain what it was. Now, it tracks the country’s No. 1 ad type — digital. Digital ads passed broadcast TV for the first time, and by a healthy margin, $2.7 billion. Passing TV is another milestone, coming just a year after digital surpassed print (newspaper + magazine) spending. Now, its lead over newspapers, as seen in the IAB chart below, is more than two to one, $42.8 billion to what IAB counts as newspapers’ $18 billion.

Curiously, that last number — part of a study PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers) did for IAB — counts $5.8 billion less in overall newspaper advertising than does the Newspaper Association of America (NAA), which released the other big summary 2013 report.

That’s a big difference — 25 percent. How come? (“It was sourced within PwC data,” offers PwC’s Steven Silber in explanation.)

Metrics are a big issue in the web world, but this ad delta — print and digital combined — is an outsized one. Whichever number you want to use — $23.8 billion or $18 billion — is highly meaningful. But your choice won’t change our tale much. The gulf between digital and newspaper advertising is now enormous, and still growing: Digital advertising grew 17 percent year over year.

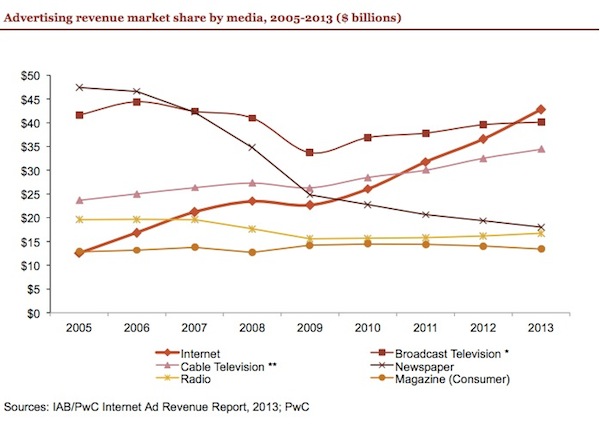

The graphical time series reinforces the numbers and puts squiggly lines to the lost decade for newspaper companies:

So, as digital advertising overall grew by $6.2 billion in a year, newspapers’ digital ad take increased by only $50 million — less than one percent of that six-billion-dollar growth.

So, as digital advertising overall grew by $6.2 billion in a year, newspapers’ digital ad take increased by only $50 million — less than one percent of that six-billion-dollar growth.

That’s a fairly incredible number. But it’s not a surprising one.

Each newspaper company reports (and internally allocates) its digital ad revenues by its own standards, so it’s tough to get apples-to-apples comparisons about how well these publicly reported numbers differ company by company. (Not to mention the many newspapers going private and only selectively releasing any data at all.) Is McClatchy’s digital-only revenues report significantly different than Gannett’s, or A.H. Belo’s?

What we can see in this NAA assemblage of numbers is that digital advertising growth has become an increasing challenge for all newspaper companies. NAA’s compilation is a fairly comprehensive extrapolation, based on 24 newspaper media enterprises, including all the public companies and some private ones. Its aim: to “cover all regions of the country and all circulation size groups.”

It shows this troubling trend in digital ad revenue growth over the past few years:

That takes us back to the recession-wracked year of 2009, when overall advertising dropped 19 percent — and that’s what took the breath out of the industry. Digital advertising, unsurprisingly, declined 11.8 percent that year. Before that, it all felt like upside: Digital ads grew at annual rates between 18 percent and 31 percent between 2004 and 2007.

This is where we need a New Yorker cartoon: Silver-haired mid-aughts newspaper CEO standing in front of chart, presiding at an impressively long, carved from a single exotic tree and flown in from wherever, whatever-the-expense, table. Pointing to a drawn five-year spreadsheet, he’s saying, “Yes, the down arrow of print advertising is regrettable, but manageable. Look at the up arrow of digital ad growth! As you can see, we’ll hit a crossover point of digital ad growth surpassing print ad decline, and all will be well.”

It didn’t work out that way. Few of those CEOs are left. The digital ad arrow rocketed higher and at a sharper angle than nearly anyone would have believed 10 years ago. But newspapers didn’t benefit from the boom. And the newspaper print ad arrow plummeted, a fall that now looks stuck at about an annual 8 percent rate.

What was once the great growth hope is now a popped balloon. The digital ad war looks almost over. Newspapers haven’t lost, exactly — $3.4 billion is still a lot of money — but they have been reduced to supporting player status.

Put a few numbers together and we can see that newspapers take only about 8 percent of all digital ad spending, a share that’s clearly in decline. In the old pre-Internet world, newspapers took about 20 percent of overall ad spending. Those two numbers are another shorthand to understand the destruction of the industry’s core business, as advertising once supplied 80 percent of the industry’s revenues and nearly all its profits.

Take in these numbers from the IAB report:

This week, though, it’s essential to face the average reality for the industry. That 1.5 percent digital ad growth rate says volumes. Most companies simply aren’t executing at a transformative level, and their continued cutting of staff and product reinforces that often dismal reality.

A few have prioritized print over digital — the Orange County Register’s Eric Spitz is the most vocal in that camp. Most, though, are trying to focus on digital — they’re just not succeeding.

The IAB data tells us something else about the 2015-18 digital ad ecosystem: Publishers may succeed best by aligning themselves with one or several of the top 10 players. Those players’ ad tech so far surpasses most publishers’ that partnerships — and using others’ tech and reach — become essential. Take the Local Media Consortium, which grew out of major newspaper publishers’ relationship with Yahoo ad tech. It now uses Google’s DoubleClick Ad Exchange, as do many other individual chains and papers. Google is a foundation for their digital businesses.

Then there’s Facebook, now building itself into an ad network, which will no doubt be used by newspaper companies. (Many of them already resell Facebook advertising.) Riding along — finding the most profitable place nesting within the biggest ad players — is much of the future of local newspaper companies’ digital ad future.

NAA reported an increase of 3.7 percent in circulation revenue. That surprised me. I’d expected it would come in around 4-5 percent. Why? By the end of 2013, more than four in 10 U.S. dailies had restricted digital access in some form, including almost all the chains other than Advance. Some charge extra for digital access; many include it as part of single-priced print-plus-digital sub. The singular compelling idea: Get more reader revenue to help offset the awful decline of print ad money.

While 3.7 percent is good, up from the flat circulation revenue we saw in 2008-10, it’s a point less than the 4.5 percent circulation revenue growth in 2012.

There are lots of moving pieces with reader revenue, but looking at individual company numbers, it looks like reader revenue growth may already be slowing — and that would be bad news for publishers still searching for a way to first get to zero revenue growth — and then, hopefully, positive revenue growth.Let’s also remember that The New York Times’ reader revenue number is included in that 2013 over 2012 NAA industry increase of $430 million. The Times increased its overall circulation revenue by $51 million in 2013 — so that’s 11 percent of NAA’s increase right there in one paper.

(For context, The New York Times’ circulation revenue equals about 7.5 percent of all U.S. circulation revenue. For clarity, the Times’ 2013 net increase in reader revenue was $51 million, despite its reporting of what is now a $160 million run-rate in digital-only subs. The $100-million-plus difference? The Times, like all dailies, continues to lose print subscribers, and their money. Just this morning, in its 1Q earnings call, the company noted that print circulation dropped 6 percent in daily copies, 2.5 percent on Sunday. So figure this: For every two dollars lost in print reader revenue, it is gaining three in digital. That’s a tough tradeoff, but one that seems to be working. In fact, with print advertising just reported to be 4 percent up for the first quarter, the Times is doing decently in print overall.)

Why might reader revenue increases be slowing, a topic that needs to be deeply explored? Consider these possibilities:

It’s too early to know what’s yet true, among that mix-and-match set of possible scenarios. Something, though, seems afoot.

One could say the numbers are sobering. But this is an industry that was shocked into sobriety years ago. Overall, NAA put the best face it could on its numbers, noting industry revenue was only down 2.6 percent. That’s still down, though, and those digital ad and reader revenue growth rates are going in the wrong direction. It’s a performance that may raise new questions for the spate of new owners, and the would-be buyers of properties on the market or soon to come to market. As the industry sells off Cars.com, newspaper sellers may find its hard to put a fresh gloss on a used paper.