There’s a kind of unspoken promise that comes along with any delayed reading service: At some point, you’ll have time to read this really great thing. But as anyone who has stared into the void of an Instapaper or Pocket queue knows, that’s often a pipe dream.

What if you could rescue your favorite saved reads by putting them into print, with one click? That’s the idea behind PaperLater, a new service that lets users create a personalized newspaper from their favorite must-reads from around the web. It’s the latest creation from the Newspaper Club, the U.K.-based company we last wrote about then it created a “robot” newspaper for The Guardian.

PaperLater is a continuation of that work; the same algorithms that automatically laid out Guardian stories will now let anyone easily throw together an edition of the web’s best reads. What’s new, and what makes the service slightly more approachable to a wider audience, is a browser button for saving stories to PaperLater — and the individualized nature of single-issue printing.As you save up stories, PaperLater keeps track of how many pages remain before you’ve filled a complete issue. Right now, PaperLater is only available to people in the U.K, where each issue costs £4.99, (roughly $8.50 for people on this side of the Atlantic). Users can only print a single copy, and the paper is delivered to you through the mail. The whole process takes 3-5 days.

A personalized, algorithm-backed newspaper fed off the writing of the open web sounds like a perfect anachronism for the world of publishing in 2014. But the on-demand newspaper has long been a goal of Newspaper Club, said cofounder Ben Terrett. The company was born five years ago with the idea of making it easier for people to create their own newspapers through better technology in design and printing. The company’s printing business is more boutique in nature — small creative runs for groups or individuals rather than larger products with publishers.

The backbone of Newspaper Club is ARTHR, a tool that allows users to pull in content of their choosing, either their own text and photos or material from around the Internet. Working with The Guardian motivated the company to see what it would take to produce a paper that was completely arranged by an algorithm. “With the Long Good Read, we set this target that one person should be able to make a newspaper in one hour,” said Tom Taylor, the company’s head of engineering.

Do people really want a personalized newspaper, even one that only takes a few clicks? Taylor said he uses PaperLater in the same way he uses Pocket or Instapaper, ultimately deciding whether he wants to sit down to read something in print over a weekend or on his phone during a commute. It fits into a different modes of reading, he said.

“I think it suits people who maybe aren’t buying newspapers as much as they used to, but they enjoy the mix of news and comment that they see in their Twitter stream, but want to take it away from the Twitter stream and all that blah that goes with it,” Taylor said.

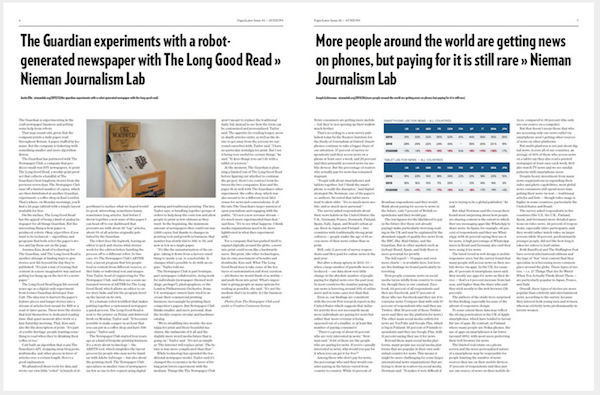

Both Terrett and Taylor say they’re not nostalgic about print, but instead see it finding more select uses for specific reading experiences. In the same way some kinds of content work better on a phone or tablet, others might be best in print, they argue. What makes PaperLater remarkable is the ease and automation of creating a paper. But the finished product very much looks like it was created by a robot. That’s partially due to the fact that the design needs of a paper are different from, say, a blog. (Take a look at this 22-megabyte GIF showing how an edition of PaperLater is made.) For example, here’s a bit of Nieman Lab, all ready for print:

For a certain subset of Internet dwellers, delayed reading tools are a way of bringing order to the daily bounty of new and unexpected things to read. Rather than letting a link slowly decay in a tab, or throwing up your hands and declaring bankruptcy on your story saver of choice, those stories could now show up in your (physical) mailbox.

Terrett said committing to a printed product — something that will be delivered to you and sit on your table — is a great motivator to catch up on your delayed reads. “There’s so much great content, it’s just impossible to read it all,” he said. “This is just a way to help you do that, really.”

Dan Hill, one of the service’s beta testers, said one of the joys of using PaperLater is taking part in the process of making the paper. “While the layout of the paper ‘just happens,’ there is a pleasing sense that you’re building a collection; not exactly making a newspaper in the sense of editing it, or laying it out, but building something nonetheless,” Hill said over email.

Hill, the executive director of futures and best practices for Future Cities Catapult in the U.K., is a fan of the Newspaper Club for its “‘slow’ approach informed by bespoke design as well as template-driven production.” Hill said PaperLater isn’t a replacement for saved reading services — he continues to use Readability to catch up with stories on his iPhone, iPad, and laptop. Instead, Hill sees PaperLater as complimentary, ideal for long-form stories that are less timely. “PaperLater, in some senses, merely reflects the way I read anyway — I hop from site to site, story to story, stimulated by front pages, tweets and recommendations — but all of that was in the browser,” he said. So far, he’s saved stories from the London Review of Books, The New Yorker, The Guardian, The Verge, and The Atlantic, among others.

Stories from a variety of publishers, printed in a newspaper, then sold to a customer — sounds like a case for a copyright lawyer. While Hill thinks it’s ultimately good for publishers to have their work read through services like PaperLater, he sees the problem in not paying those publishers directly for work they might charge for in other mediums. “It is certainly slightly ironic that they don’t receive any revenue from the story being printed on paper, when they are in a business in which they are losing money as not enough people are reading their stories on paper anymore,” he said.

Taylor says the company has had discussions with a number of publishers about PaperLater — both about how the technology works and the copyright implications. Taylor said they believe PaperLater is on solid legal footing because users can only make a single copy of a paper for their personal use rather than mass publishing.

But the company may also explore ways to partner with other companies in using the PaperLater software, Taylor told me. The Long Good Read offers one model. Terrett said another opportunity could be to work with other reading or link-sharing platforms. The goal would be to have a “save to PaperLater” option be available “where people are sharing links and bits of staff passing around,” he said.Taylor doesn’t expect PaperLater users to be the type of people who have newspaper subscriptions or already have a history with print: “It’s for a new, different audience. It’s for people the newspaper groups already lost. They lost them to Twitter.”