Editor’s note: The new issue of our sister publication Nieman Reports is out and ready for you to read.

Editor’s note: The new issue of our sister publication Nieman Reports is out and ready for you to read.

(We’ve already shared a couple of pieces from it with you, but check out the whole issue.)

I write a column for the print edition of the magazine. Here’s mine from the new issue.

“There is no need for advertisements to look like advertisements. If you make them look like editorial pages, you will attract about 50 per cent more readers. You might think that the public would resent this trick, but there is no evidence to suggest that they do.”

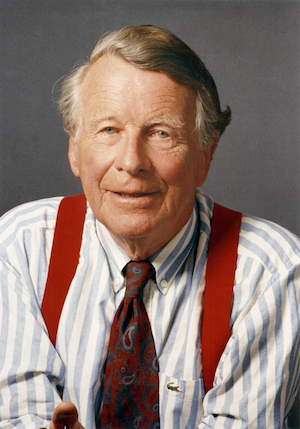

That was David Ogilvy, the Mad Men-era advertising wizard, in Confessions of an Advertising Man, 1963.

That was David Ogilvy, the Mad Men-era advertising wizard, in Confessions of an Advertising Man, 1963.

When we look back on 2014 in the news business, we may think of it as the year that Ogilvy’s maxim went mainstream, accepted in the world’s top newsrooms.

In January, NYTimes.com ran its first piece of what’s come to be called native advertising. It had “The New York Times” blazed across the top of the page, and it had a lot of the visual DNA of a Times article — a headline about millennials in the workplace, about 700 words of copy, and even the honorific Mr. and Ms. of Times style.

But above that headline, in 12-point type, were the words “Paid for and posted by Dell.” The byline went to a freelance writer with a Dell logo next to her name; the typography looked different from what you’d see on a Gail Collins column. And at the bottom: “This page was produced by the Advertising Department of The New York Times in collaboration with Dell. The news and editorial staffs of The New York Times had no role in its preparation.”

In March, The Wall Street Journal published its first native ads, under the rubric of “Narratives.” USA Today joined in May, the same month the nonprofit Texas Tribune debuted paid placement for op-eds. The Washington Post ran its first native ads last year. Even the unabashedly liberal Guardian is in the game, running pieces praising, say, Ben & Jerry’s earth-friendly treatment of its ice cream waste products. They look a lot like standard stories — but look a little closer and you’ll see that the byline is the Anglo-Dutch multinational Unilever, Ben & Jerry’s corporate parent and The Guardian’s “sustainable living partner.”

If you’re like many journalists, the last few paragraphs have made you feel a little unclean. The separation of editorial content and advertising was drilled into most of our heads at a young age — that first journalism school class, that first crusty night city editor. The credibility of the news, forever challenged, would seem to be deeply wounded if something that looks like an article is up for sale.

And yet it’s hard to find a major news company that isn’t looking to native as an important part of their business strategy in 2014. Like it or not, native advertising is here to stay — no longer reserved for digital natives (Gawker, BuzzFeed, Quartz) and a few traditional outlets with an edgier digital presence (Forbes, The Atlantic).

And, as David Ogilvy foretold, there hasn’t been much sign of public resentment, much less a public revolt. There have been a few PR missteps — The Atlantic’s sponsored puff piece about the Church of Scientology last year comes to mind — but thousands of other native ads have been published to a collective audience yawn. Is it possible that what readers care about and what journalists care about aren’t always the same thing? Wouldn’t be the first time.

Why is native advertising so appealing to publishers? Let’s start with the obvious: money. You may have heard that a lot of news companies are in need of it. Native attracts significantly higher rates than most other forms of digital advertising; The Guardian announced its Unilever “partnership” as a seven-figure deal. (Estimating the size of the native ad market is complicated by the fact few agree on what the boundaries of “native” really are. BIA/Kelsey predicts it’ll be a $4.6 billion market by 2017.)

Publishers also love native advertising because it plays to their strengths. Before the web, a newspaper could sell businesses on an amorphous idea of its “audience” and the idea that putting ads near stories would somehow, fuzzily, equal impact. And even today, most news organizations have only the broadest idea of what makes one online reader different from another.

But the kings of online advertising — Google, Facebook — are swimming in user data. Google knows what you’re searching for, what you’re emailing about, where you’re looking for directions — even what products you almost-but-not-quite bought online. Facebook knows who your friends are, where you went to school, whether you’re single, what brands you like. All that data means they can target ads at you far more effectively than a newspaper website that doesn’t know much more than the fact you’re interested in news about Kansas City.

The war of user data is a war that news companies have lost. Print advertising continues its steady decline, but for most news companies, online advertising growth isn’t doing much to help the bottom line — the new money goes to the digital giants, not the local daily.

So native advertising — which is fundamentally about brands, both the news organization’s and the advertiser’s — is seen as a place where publishers can still have something to offer. For Dell, attaching its name and content to The New York Times is something that’s hard for a social network to match. For GE, sponsored content on sites like Quartz and The Economist attaches a vague innovation-friendly feeling to its brand. For the National Retail Federation, which has bought space for what sort of looks like an op-ed on Politico, native gives direct entrée to an audience of Hill staffers and political movers.

Why is it called “native” advertising anyway? It’s meant to embody the idea that, on any given environment, a piece of advertising will be more effective if it feels native to that platform. An ad on Twitter should look like a tweet. An ad on Facebook should look like a Facebook update. An ad on a Google search should look like a search result.

At one level, that makes sense if you’re trying to make ads effective. At another, it’s essentially the opposite of the church-state wall many of us were taught.

But whether you like it or not, native advertising is now inside the big news tent. Maybe it’s just a new iteration on the advertorials newspapers and magazines have run for decades. Maybe it’s a scurrilous devaluation of journalism. Either way, it’s here, and at the highest levels of the business. What journalists can do is push for clear labeling, shame those who fall short, and hope that the business sides of their outlets won’t turn their brands into a non-renewable resource.