On Monday, NASA released a high definition version of one of its most iconic photos ever, the Pillars of Creation — a shot from the Hubble Space Telescope that shows three massive columns of gas about 6,500 light years away. Atlantic senior editor Alan Taylor, who runs the site’s In Focus photography blog, knew immediately that he wanted to feature the photo, but he didn’t have an easy way to showcase it on the site.

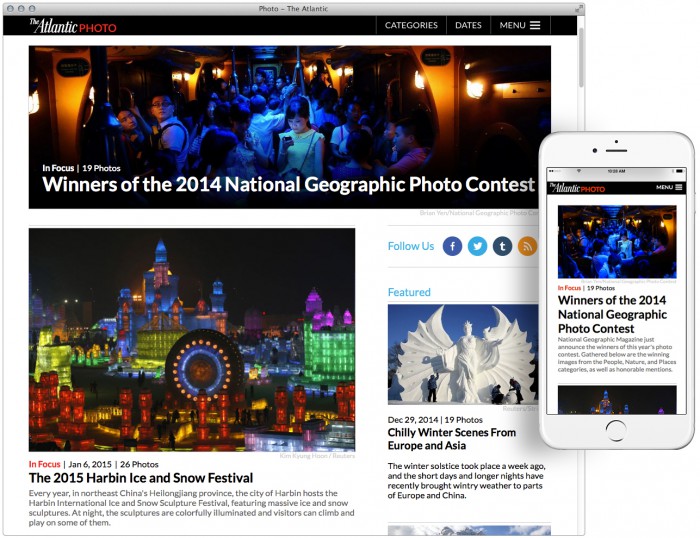

Since Taylor launched an earlier version of the site at The Boston Globe in 2007, In Focus has known for longform photo storytelling, featuring huge, high-quality images. (He joined The Atlantic in 2011.) Taylor felt that he couldn’t just post the one NASA photo on its own; The Atlantic covered it elsewhere on its site.But starting today, Taylor will be able to mix in shorter quick hits with the long photo essays he’s been known for, as The Atlantic launches a redesigned photo vertical, now known as The Atlantic’s Photo section. The shorter posts will be housed in a new subsection called Burst.

This is the latest example of Atlantic Media shifting around the branding and structure of its constituent sites. Last October, for example, it brought The Wire (née The Atlantic Wire), its quick news aggregator, into the main Atlantic site. Earlier, The Atlantic Cities became CityLab.

By more closely aligning the photo site with the main Atlantic brand, Taylor is hopeful that he’ll be able to grow the site’s audience while also bringing in new forms of photo storytelling.

“For me, the main point that I’d love people to understand is that this change is our way of saying not only do we enjoy what we do and feel that it’s of value and continues to be valuable to us, but we’re going to be committing to do more and get it to a larger audience,” Taylor told me. “This is an expansion of what we do.”

When Taylor first began his large-format photo storytelling at the Globe, it was unique, bringing in 8 million pageviews a month. But the visual web has come a long way since 2007, as platforms like Instagram have become ubiquitous and many online publishers have embraced giant images and photo-heavy designs. To that end, Taylor and I talked about how he plans to further to develop the photo section as competition continues to grow. We also touched on The Atlantic’s approach to the redesign and how Taylor thinks about maintaining the site for mobile and social audiences. Here’s is a lightly edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

With doing that, that gives me the freedom to do different types of photo essays. For years now, I’ve been doing longform photo essays pretty much exclusively, and it would be nice to once and awhile just throw out a single image, or maybe do something in the future that involves different types of layouts. But for right now, that’s kind of the difference — I wanted to be able to do short form as well as longform as well as to kind of line it up the rest of the way the site is laid out.

That’s just kind of structural, but what I’m excited about is that the images are going to be both larger and smaller. It’s responsive, so it will work well on big screens — bigger than what we support now — and it will work well all the way down to handheld mobile and iPhone portrait mode. It’ll all just look really good, hopefully.

I’ve been doing the photo editing now for seven years, and now it’s nice to have the ability to do it just whenever something comes up. If I want to do a historic photo of the day, something from the archives, or something from the Library of Congress, or a really amazing photo was just released by NASA — I just don’t really have an easy outlet for that, and it’d be nice to have. And now I’m going to have it, hopefully.

Right now, if you wanted to share a single image from one of our old essays, either you’d grab the entire very long URL with a little anchor tag at the end that would take you right to that single image, or you could right click and get the source of the image and share it out of context. That happens — it’s the web, people do that — but we want to let people have any way that they want to share something and just go for it.

I mean everyone is pretty much carrying a camera with them 24/7. It’s difficult. About all I can really do — and I know what has really served me well in doing this — is just trusting my gut and putting together a good story. You can’t force your way into someone’s Facebook News Feed. You can just present yourself regularly as a place to come for quality stories. That’s what I feel what I’m fairly good at and I’ve been working hard to do. Anything else feels forced or false.

If you’re pandering to social media, if you’re going for clickbait, it cuts away at any sort of storytelling.

But I do really enjoy historical stories and going through archives. Just last year, I finished a long series of articles on World War I and I got to travel to the National Archives in Washington and go through their physical archives. I digitized some images for the first time and put those in there. That was just amazing.