Earlier this month, as the U.S. Supreme Court was set to hear arguments in a major abortion-rights case, Lizzy Acker, web editor for the Portland alt-weekly Willamette Week, wrote a story about how a 1908 Oregon law could impact the current case before the court, which deals with a Texas law that puts restrictions on abortion providers.

Comments on an article about abortion can quickly turn toxic. But for Acker and Willamette Week, the comments were, perhaps surprisingly, relatively polite.

That’s because the paper was using Civil Comments, a commenting platform from Civil, a Portland-based startup, that aims to produce respectful dialogue in comment sections through a system that crowdsources comment moderation. Willamette Week was the first outlet to adopt the platform.

In the comments below her story, Acker got into a debate about abortion laws with some readers, and though they disagreed pointedly, the conversation didn’t devolve into name-calling or harassment.

“A guy got in a conversation with me, and he expressed a full thought,” Acker said. “He didn’t just call me a baby killer. I expressed a full thought. It’s interesting, even for me, to figure out how I can disagree with somebody and maintain a civil attitude and keep it constructive, at least a little bit.”

“It requires you to think about your argument a little more,” she said. “I think the comments are longer and the thoughts are more developed.”

Thursday status: arguing CIVILLY with racists in the comments. https://t.co/O4BrwKS1oC

— Lizzy Acker (@lizzzyacker) March 17, 2016

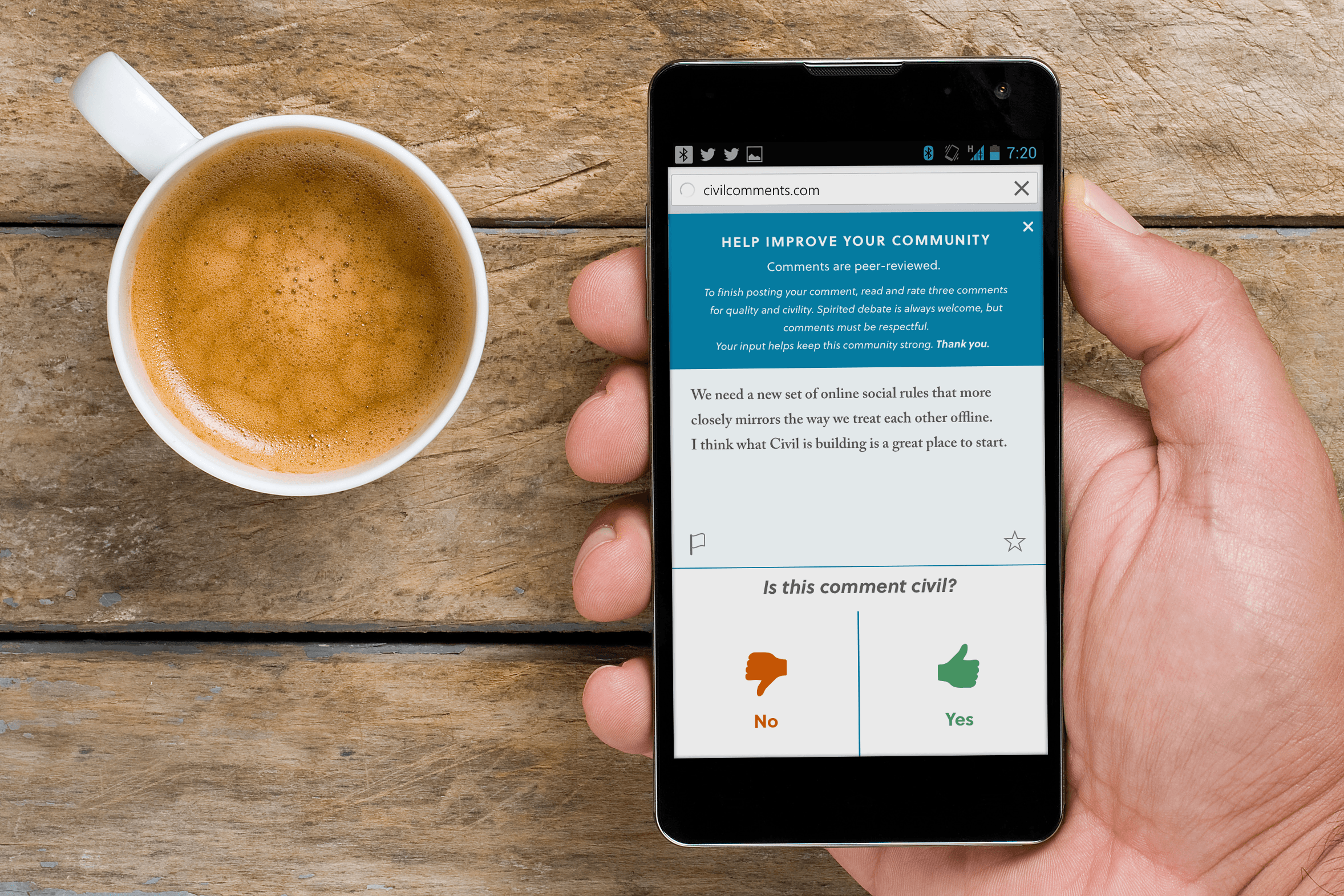

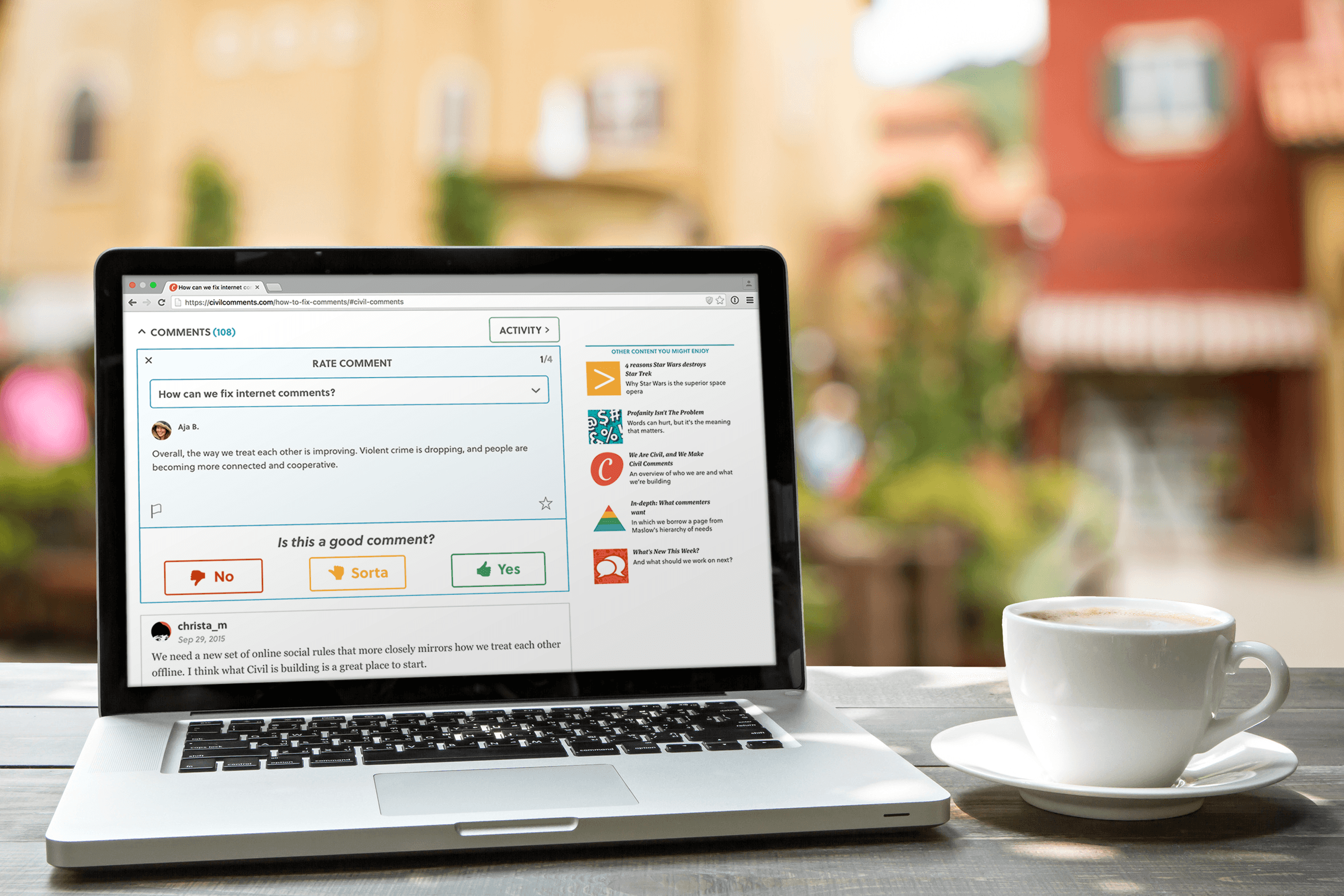

Commenters are shown two random comments from elsewhere on the site, and must rate the comments’ quality and civility and determine whether they include harassment, abuse, or personal attacks. The user is then asked whether his or her own comment is civil before it’s posted.

Civil asks two questions about each comment so that users are forced to separate their opinion on the comment’s content from its tone.

“What this very effectively does is get them to realize, ‘Okay, this is not me just shouting into a void. I can’t just say whatever I want. I have to think about saying things respectfully and not insulting or attacking people,'” Civil CEO and co-founder Aja Bogdanoff told me. Otherwise, the comment won’t be published.

If a comment is repeatedly marked uncivil, staffers are alerted to review it.

Civil also uses several proprietary language-processing algorithms that assist the crowd-sourced moderation by provisionally pre-approving or rejecting comments. Final judgment, though, comes from the commenters themselves.

The behind-the-scenes algorithms are designed to prevent abuse and keep users from gaming the system. Bogdanoff wouldn’t go into specifics about how they work.

“If you don’t carefully design around abuse and fraud, you’ll end up with a system that’s even less fair than the old-fashioned approach,” Bogdanoff said. “We’re making sure we’ve built enough behind-the-scenes abuse prevention to keep the system fair, not create an echo chamber, and not allow eople with a certain perspective dominate the conversation.”

Some have critiqued Civil Comments for trying to stifle free speech or sanitize dissenting views, Bogdanoff said, but she estimated that only about two percent of comments on the system have been rejected.

“When you moderate out the hate speech and the personal attacks, you actually end up hearing from a wider group of people,” she said.

News organizations of all sizes are trying to improve their comments sections. Outlets such as Reuters and Mic have eliminated comments on their sites altogether. Others have taken more creative measures: The Jewish culture site Tablet last year decided to charge readers to comment on its site. And some larger outlets, such as The New York Times, have full-time staff members who focus exclusively on regulating reader comments. Bogdanoff and her co-founder Christa Mrgan launched Civil to make it easier for smaller outlets to moderate comments and keep reader discussions on their own sites instead of farming them out to platforms like Facebook and Twitter.“It’s a shame when your audience has to go somewhere else to discuss your work,” Bogdanoff said. “I don’t see the business advantage of driving people out to other platforms. People want to discuss the news and have a social experience around the news. If you can provide them with a compelling place to have it in the same place as your content, that’s a lot more compelling, from a business perspective, than needing to figure how to monetize all this traffic that’s leaving for Facebook.”

Civil Comments is a subscription service, and so far the system is being used by two Oregon papers: Willamette Week and The Register-Guard, the daily newspaper in Eugene. Civil is looking to expand to other outlets as well, Bogdanoff said, adding that it’s focusing on other local papers and larger blogs. “As we grow, we’ll be looking to get involved with larger media companies and other types of platforms and providers,” she said.

Willamette Week switched to Civil in January, and The Register-Guard followed in February. Representatives from the papers said that in the weeks since they made the switch, the number of comments they’ve received has fallen by about 25 percent.

Though the number of comments has decreased, the quality has improved, Acker said. There’s much less trolling, and Civil’s multi-step commenting process has eliminated spam.

“Sometimes people complain in the office that our comments are way down,” Acker said. “But we’ll always have stories that don’t have any comments. We did have stories that had hundreds of comments before, but a lot of those were back-and-forth between two guys. I don’t think that the number of comments has directly correlated to traffic. When we have stories that people want to read, there are more people on the site, and more people commenting.”

Despite the decrease in overall comments on his paper’s site, Register-Guard managing editor Dave Baker said he’s optimistic that the improved commenting environment will bring in new commenters. In fact, the number of comments has begun to tick back up. The Register-Guard has had more comments last week than they previously averaged with Disqus, Bogdanoff said.

“My hope is that over time we will attract some of the folks who were scared away over the years,” he said. “Hopefully they’ll give us another try.”

Acker said Willamette Week is developing strategies to get readers to use the commenting system. The paper promoted the new comment system in a story on its site, and Acker is trying to spend more time in the comments to show that it’s now a healthier environment. Still, she said, she thinks it will take time for people to adjust, and that it will ultimately get easier as additional sites move onto the system.

“That is Phase 2: How do we let people know that they’re welcome here and they aren’t going to be attacked for their ideology, their body, whatever?” she said. “There aren’t going to be threats. There’s going to be conversation.”