Text messaging is, by far, the most popular feature Americans use on their phones. Ninety-seven percent of American smartphone owners send or receive a text in a given week, according to a 2015 Pew study. Dedicated messaging apps like WhatsApp, which are especially popular overseas, are also gaining in popularity in the U.S.; Pew reports that 36 percent of smartphone owners use messaging apps.

News organizations from the BBC to small startups see potential in the messaging format for news, and many outlets are exploring ways to integrate messaging into their coverage.“It’s very intimate to allow an organization to have a conversation with you,” said Andrew Haeg, the founder of GroundSource, a platform that enables journalists to connect with communities via text message.

“I can’t imagine many stronger indications of one’s desire to engage with a news organization than adding it as a contact in their address book,” he said.

GroundSource is based out of Macon, Georgia, and works with news organizations and community groups throughout the United States and around the world to help them reach underserved communities. Outlets can license the technology, and GroundSource sells monthly plans (including a free tier) that are priced based on how many messages are sent each month.

Haeg, who is also a co-founder of American Public Media’s Public Insight Network, spoke with me about how GroundSource works, what the best practices are for soliciting responses from potential sources, and how GroundSource is adapting to messaging apps. Below is a lightly edited and condensed transcript of our conversation:

Often, especially in lower-income communities, the media only enters the community in times of crisis, when there’s been a crime or disaster. GroundSource can eliminate many of the barriers between communities and news organizations by making it as simple as sending a text to communicate and share an experience.

The Public Insight Network was much more focused on the concept of becoming part of a network of sources who are shaping the news. That can be powerful, but it’s only appealing to people who believe the following: 1. Journalism is important to our community. 2. I have a role in shaping that journalism. 3. I have the ability to articulate that experience in a way that someone else may find valuable. 4. I have the time to sit down and fill out a survey.

There are a lot of psychic barriers to participating in something like that. Even with all those barriers in place, the Public Insight Network manages to get a lot of people engaged with their news coverage, but if our job as news organizations — and especially public media organizations — is to serve our entire community, we’ve got to make it so that everyone in the community feels welcome to participate.

All you have to do to respond to a prompt or call-out is text a word to that phone number. After that, the pressure is taken off of you to step forward and engage. That’s a very different dynamic from social media.

At the same time, texting has emerged as something that anyone can do. My parents can text, my kids can text, it’s a very natural way of communicating. And with all the SMS clones out there — from WhatsApp to WeChat to Telegram — the behavior of texting that’s now being cloned in a smartphone app feels even more compelling. Quartz moved to a texting-like app because it feels very much like you’re part of a conversation. There’s nothing as intimate as allowing an organization to have a conversation with you. I can’t imagine many stronger indications of one’s desire to engage with a news organization than adding it as a contact in their address book.

In the process, they’re getting information that, for a journalistic organization, is pure gold. They’re getting validated sources who have provided a phone number, who are willing to be contacted, who are sharing information that’s new and relevant on topics that are often difficult and problematic, whether it’s gun violence, healthcare, or education. As an expression of what’s possible with GroundSource, Listening Post is great. Now a bunch of news organizations are starting to use it, from ProPublica, to KPCC in Los Angeles, to Jersey Shore Hurricane News, to human rights organizations in South Africa, to community organizations here in Macon. So it’s not just for news organizations; there’s a broader vision.

KPCC has been doing some call-outs around El Nino as a way of getting used to the tool. ProPublica plans to publish a story around call-outs that they did on rent control. Alabama Media Group has used it for a number of topics, from overcrowded prisons to healthcare to asking Alabamans for their favorite “Momisms.” They put together a video piece stringing those together. Because it’s a conversational form of engagement, it allows you to ask things that aren’t so heavy-duty all the time.

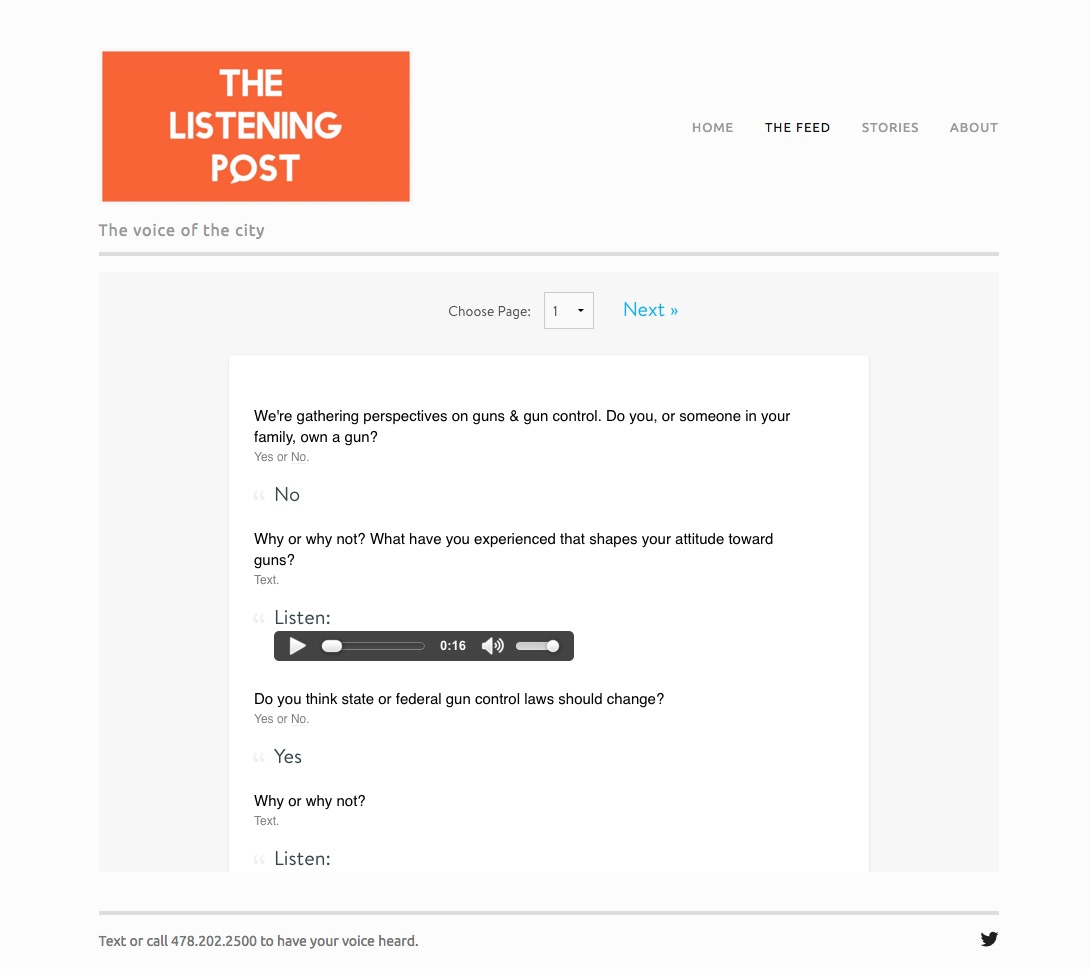

In Macon, we asked people for their perspectives and stories around gun control. One woman wrote in saying that her son was killed walking to the gas station. She was starting to teach her other kids how to use guns because she wanted them to protect themselves.

This form of engagement, because it’s meeting people where they are and because it’s conversational, often draws out far more nuanced and real stories from people who are dealing with things. If you open up the comments section of a story on gun control, you’re going to get the typical people who are circling the wagons around a certain point of view and are coming into the comments to try and win that argument. But if you push a specific request for stories about gun control, people are going to respond to those questions in a more honest way.

If you only knew that this woman was teaching her kids to use guns, you might assume something about her experience or her point of view, but once you’ve read her story, you learn that she’s not a member of the NRA, she’s not a gun enthusiast so to speak, but she feels scared for her kids’ safety.We had other people who texted in, who were from generations of hunters and parroted the “people kill people, guns don’t kill people” point of view, but then went on to say that gun control laws need to change and there ought to be much stricter vetting. That’s a nuanced point of view. If that person had entered the comments section, they’d probably be arguing on behalf of people who are against various forms of gun control, but here, because they’re asked to share their experience and invest something in the conversation, they bring a more nuanced perspective to the table.

With the gun control one, we just asked, “Do you own a gun?” People could answer that in a second. We followed up with a more complicated question: “What about your experience shapes your attitude toward guns?” We originally had “Why or why not?” as the second question, and we got very short answers back. But when we asked about experiences, it was as if we had flipped a switch, and we started getting these really amazing personal stories. People wrote at length; it wasn’t just the five- or six-word response that you might expect over text.

People need to know that you want them to elaborate. They are not often asked directly to tell their story: On social media and in comments, there’s an open box to type into, but it’s not as someone tapping you on the shoulder saying, “Tell me your story.” That’s an endlessly compelling request for most people, and if they know someone is listening and that there’s a purpose for it, they will step forward and tell it.

The next phase is a mix of broadcasting and private messaging. The flow we built for SMS works exactly the same way on messaging apps, but until recently we weren’t seeing news organizations seek out tools to help them engage over messaging apps. Social media is really an extension of the broadcast model: It may be done in a more conversational or engaging way, but the principle of social media isn’t a conversation. It’s sharing and following and liking. With messaging apps, you have to engage in a conversation. You can broadcast into messaging apps, but that’s not nearly as engaging as having an actual conversation with someone.

Think of a survey delivered over SMS: That’s an automated form of a conversation. We extend that by enabling you to go seamlessly from that automated conversation to an actual human conversation. If a source responds to a back-and-forth about gun control by answering a few questions, that feels conversational, even though they know it’s a computer sending them automated messages each time they respond. But a producer can be in their feed within GroundSource, too, and immediately respond and say, “Hey, thanks so much for sharing. Do you mind following up for a quick phone call?”It feels totally seamless. I think that’s where we’re evolving, to this mix of bot-like interactions over SMS and messaging apps and actual person-to-person human interactions, and making that manageable for news organizations.

You’ve written about Purple and some others, and there are lots of people working on that broadcast model, whether it’s over SMS or WhatsApp. Quartz’s new app is just the broadcast model delivered over a messaging-like interface with some minimal interactivity built in. But GroundSource opens up the opportunity to establish a direct two-way conversation over SMS and messaging apps, pull in content, and do something with it.

I can’t give a ton of detail about how we figured out how to do it, but basically, we’re able to emulate a conversation between our system and an individual. We hope that WhatsApp evolves to explicitly support this conversation. There’s not much better of an indicator of engagement than an individual saving your phone number in their address book and allowing you to contact them. If that condition is met, then organizations like WhatsApp should support systems like ours.

Next, we’re looking at Telegram, in part because it has a far more open architecture [than WhatsApp] and there are some opportunities to do encryption, which we find intriguing. Then we’ll look at WeChat and Line. Each app has some different capabilities that we’re interested in exploring on top of the baseline messaging experience.