Fake news (an unwieldy term, but one that seems to have stuck) — dupes American readers on both sides of the political spectrum. And Facebook, the main vector for all these fake news ills, has suggested it’s working on products to tackle misinformation and hoaxes on its platform, including “better technical systems to detect” fake posts and labels for stories that have been flagged by the community (see Mark Zuckerberg’s post about the social network’s roadmap here).

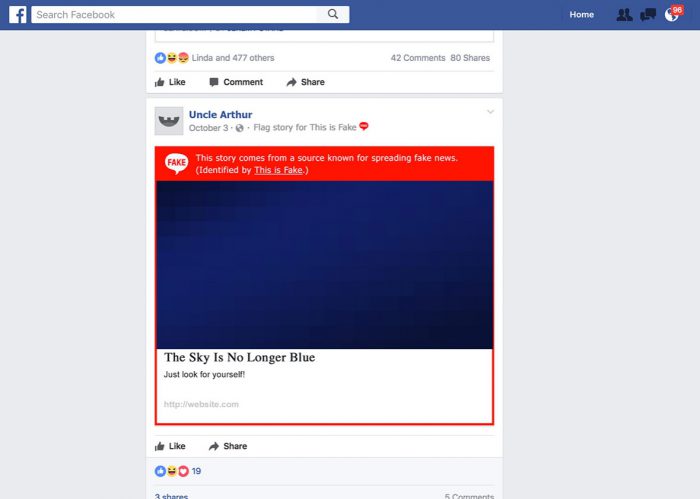

While Zuckerberg has given no timeline for these fake news defense efforts, Slate has already built its own version of a solution (or the beginnings of a solution). This is Fake, which emerged out of a post-election hack day and was released this week, is a Chrome extension that slaps a warning label onto confirmed fake news stories and sites, and lets users who’ve authenticated it through Facebook flag suspicious posts on their own (for now, moderators from the Slate editorial staff will be reviewing these crowdsourced posts).

The tool is already loaded up with a list of problematic “news” sources, based on various guides that have floated around since the election, which the Slate staffers then culled into a working database. Some of those internet guides, such as one highly circulated list by Merrimack professor Melissa Zimdars, had, controversially, included satire sites as well as Breitbart and Glenn Beck’s The Blaze. This is Fake, however, is focusing on completely fraudulent, completely fake, no-kernel-of-truth-whatsoever stories — not inflammatory opinion pieces and not, at least at launch, conspiracy theories.

“We’re taking a pretty narrow definition of what is fake — something intentionally misleading, intentionally false. [For example], the Pope didn’t endorse Donald Trump, that’s just a blatantly false statement,” Dan Check, Slate’s vice chairman, said. “Divining people’s intentions may be hard, but the reality is, we’re a media company, and one of the things we do all day is separate fact from fiction. This is not a new problem for our staffers. It’s a set of judgments, a set of discernments, that we hire people to make.”

(In a piece announcing the launch of This is Fake, Slate’s Will Oremus clarified further: “We also distinguish between news and conspiracy theories, which may be genuinely believed by the people who purvey them. Our database focuses on the former, although it’s worth noting that fake news stories often have their roots in conspiracy theories.”)

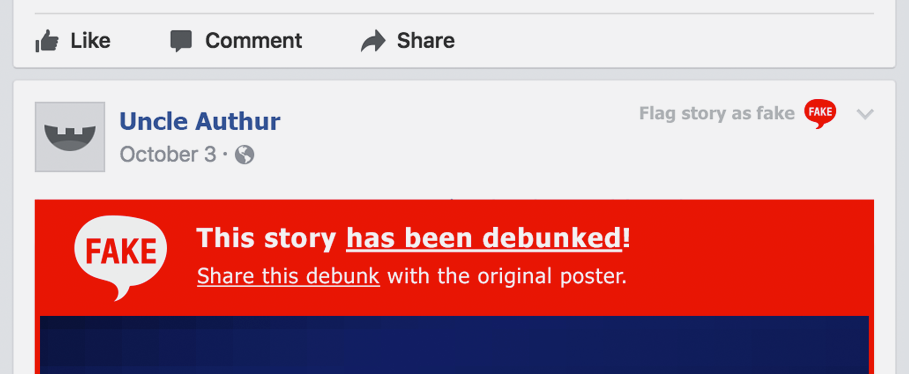

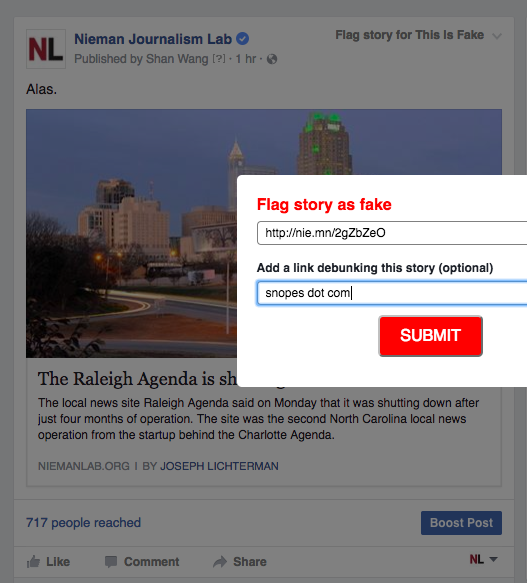

The This is Fake extension offers participating Facebook users the option of including a link to a debunking story. Users are encouraged to counter Facebook friends sharing false information with such links to factchecks.

“We wanted to do this in a way that would let people take action, and we’re doing this in a way that actually encourages more speech — this is fighting bad speech with more speech. We’re not hiding articles, we’re not removing links or blocking them out of people’s newsfeeds,” Check said. “We’re encouraging people to engage. We think there’s going to be a set of people who want to be on the lookout for these things. And that set of people should be engaging in a dialogue with other people, and bring some facts into the equation.” (If you’ve ever had a fight on the internet, you may have misgivings about how a well-intentioned dialogue like this could go. But does that mean we shouldn’t try to figure out ways to tamp down on the spread of fake news on Facebook?)

Slate hopes This is Fake will take on a life of its own (hence the extension lives on at its own URL, outside of Slate.com), and that other media companies will be interested in partnering on the project down the line. While everything readers flag via the tool is reviewed by Slate on the backend now, the moderation volume could become too much to handle, and Check suggested possible solutions such as deputizing the most active fake news-spotting users as moderators.But the average Slate reader, I suggested to Check, may be enthusiastic but may exist in the type of filter bubble on Facebook that doesn’t widely encounter these types of stories. (This is Fake’s landing page bears a “Made possible by Slate+ members” stamp; Check clarified that’s intended to indicate the project is something “our members will see value in our having created” and “this is not something we’re going to get advertisers to sponsor.”)

“When Joshua Benton wrote his post-election piece about the forces driving this election’s media failure, he pointed out that somewhere in his Facebook network, there were fake news stories — because of people he’s related to, people he knew. These are probably in your feed somewhere. You have a set of attachments, even for the average Slate reader,” Check said. “I don’t think the target audience here is limited to the average Slate reader. Maybe the preponderance of fake news is in a certain direction right now, but this isn’t a partisan issue. It’s about having a standard of truth, and that’s open to everyone.”