If you went offline for even a little bit of what was a three-day weekend in the U.S., you might have missed a spate of new surveys, studies, and articles about The Way We Media Now. A briefing:

Why facts don’t change our minds. The New Yorker’s Elizabeth Kolbert reviews three newish books (all published before the U.S. election, but particularly fitting now) that look at why humans are so bad at realizing they might be wrong about something. Some of it is biological: “Reason developed not to enable us to solve abstract, logical problems or even to help us draw conclusions from unfamiliar data; rather, it developed to resolve the problems posed by living in collaborative groups.” Back when we lived as hunter-gatherers, “there was little advantage in reasoning clearly, while much was to be gained from winning arguments.”

Unfortunately, Kolbert writes, “providing people with accurate information doesn’t seem to help; they simply discount it.” (Though note that this is an argument that’s easy to overstate.) Similarly, see Digiday’s “Day in the life: How BuzzFeed’s Craig Silverman debunks fake news.” Silverman: “I often feel like people expect me to have an answer for how we solve online misinformation and confirmation bias. Human nature plays a huge part in all this. It’s colliding with the big platforms and algorithms that are feeding us more of that.”

We gloss over stories we don’t want to see. The New York Times’ Upshot worked with web analytics company Chartbeat to analyze the traffic of 148 news organizations’ sites and found that “publications across the political spectrum broadly cover the news events of the day, but their readers appear to gloss over the stories they don’t want to see.” Chartbeat’s researchers categorized the news organizations as tending to have either more liberal readers or more conservative readers (and you can see the range here). The findings tie back to the confirmation bias problem discussed above: Even when news organizations cover a wide variety of stories, readers still may skip over the ones they sense they won’t agree with.

While the document is obviously Trump-inspired, “the problem is certainly not unique to the United States, or to the kind of right-wing populism Trump represents,” the authors note, and the tips here should be of use not just in covering the current administration but in covering the upcoming elections in Europe.

One overarching “do”: “Call lies lies and falsehoods falsehoods. Not doing so undermines credibility and trustworthiness with the public (even if it may infuriate partisans). In turn, cover the partisans who support powerful people who lie.”

Meanwhile, “don’t succumb to false equivalence…don’t let yourself be distracted by endless tweets and provocative asides — cover the story, not the person.” The authors also suggest that reporters “avoid going live unless absolutely necessary,” especially with sources who are known to be unreliable — it’s hard to fact-check in real-time, and live media can further publicize a lie.

Write truthful headlines, always considering how people process information. Many people will only read the headline. Information presented first and in bold font will have a greater resonance than information presented after. Putting others’ words in quotation marks, to signal, “We don’t know if this is true, we’re just telling you what they said” or even “Nudge, nudge, we know this isn’t true,” is a journalistic cop-out and is probably not understood by most readers in the way it was intended. (See: Debunking Handbook, Misinformation and Fact-Checking: Research Findings from Social Science) – @tamarwilner +@heidits +@leakorsgaard +@vehkoo

Several contributors suggested that different media organizations could come together both on a reporting level and on a broader level. There’s the idea for a “‘pooled’ White House new dashboard,” “a new kind of aggregation site for specific topics.”

While it may be difficult to encourage competing publications to collaborate on this initiative, it may help highlight the different and competing narratives that are circulating. It may also be a way of having a neutral place to debunk news articles. So, when someone on social media shares something that is incorrect (example: Trump incorrectly stating how much he self-funded his campaign), users can go to this pooled site, look at relevant articles and suggest others go there to confirm.

And there’s a call for “some sort of national or even international governing body” that wouldn’t involve the government but would investigate misconduct among member organizations:

In short, the media needs to control itself. This is not a Facebook issue, or a Twitter issue, or even a fake news issue. This is a leadership issue. Although clickbait, fake news, and other forms of misinformation are a problem, they are not the root of the problem.

Europe, in fact, is trying something like this. The New York Times reports on East Stratcom, an EU initiative designed to “address Russia’s ongoing disinformation campaigns.”

The team tries to debunk bogus items in real time on Facebook and Twitter and publishes daily reports and a weekly newsletter on fake stories to its more than 12,000 followers on social media.

But its list of 2,500 fake reports is small compared with the daily churn across social media. Catching every fake news story would be nearly impossible, and the fake reports the team does combat routinely get a lot more viewers than its myth-busting efforts.

East Stratcom is purely a communications exercise. Still, team members, most of whom speak Russian, have received death threats, and a Czech member of the team has twice been accused on Russian television of espionage.

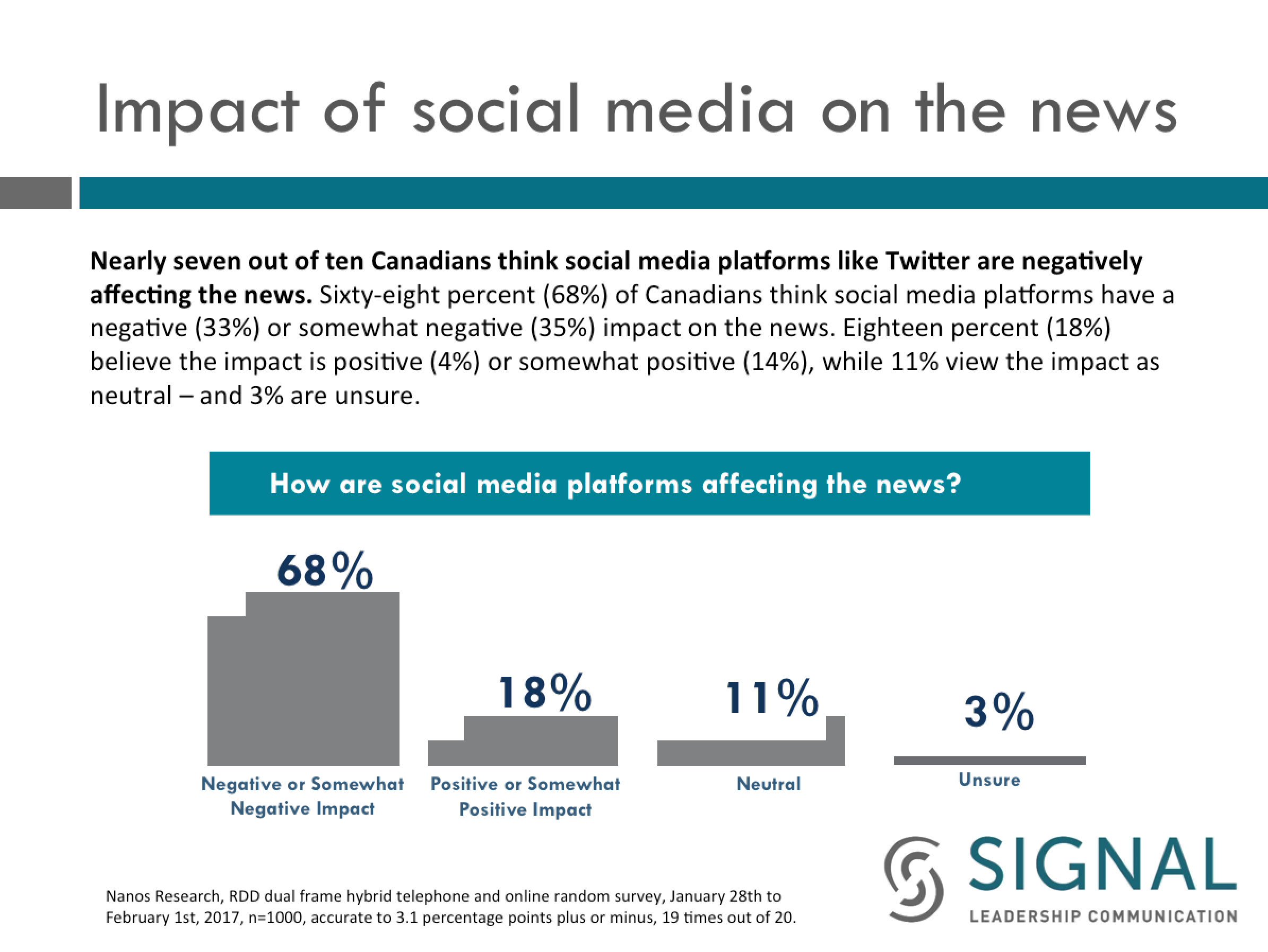

Canadians, at least, think social media is ruining the news. From a survey conducted by a Toronto firm via phone and web (and also written up in The Globe and Mail):

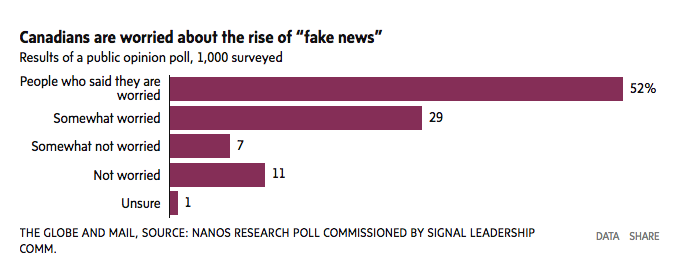

Respondents were also worried about fake news:

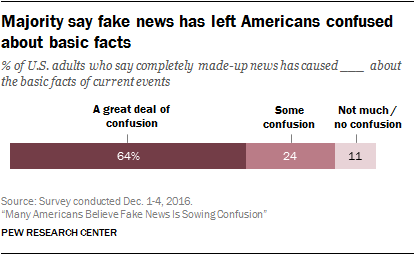

When I went searching for comparable U.S. stats, I found this from a Pew survey conducted in December:

In a Pew survey from October, meanwhile, 64 percent of social media users said “their online encounters with people on the opposite side of the political spectrum leave them feeling as if they have even less in common than they thought.”