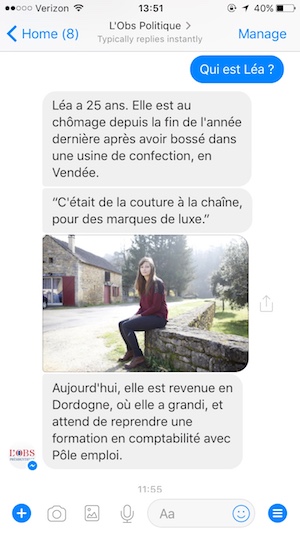

Over the past few weeks leading up to the first votes in the French presidential election on April 23, Léa, an unemployed 25-year-old from Dordogne, a region in southwest France, has changed her mind about who she plans to vote for at least three times.

First she planned on casting her ballot for centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron, then she was thinking of voting for the National Front’s Marine Le Pen, and now she’s supporting a candidate from a small party.

First she planned on casting her ballot for centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron, then she was thinking of voting for the National Front’s Marine Le Pen, and now she’s supporting a candidate from a small party.

Léa has been tracking her preference as part of an experiment run by L’Obs, a French newsweekly. The magazine is following four undecided voters from around the country and across the political spectrum to see how they’re thinking about the upcoming election. It’s using a Facebook Messenger bot to share their stories and update readers.

L’Obs launched the Messenger bot last month, and it’s been sending at least four updates per week — one about each voter. The bot allows users to choose pre-written responses to the messages that feel conversational, much like the Quartz app.The project is run by Audrey Cerdan, the magazine’s new formats editor. In 2012, she tracked a single voter over the course of three months leading up to the election. That reporting resulted in a single story.

This time around, she wanted to do something similar, but on a serialized basis. She decided to use Messenger to follow the four voters because it offered a location where readers could come back to to follow the story, it allowed push notifications, and it was a place that enabled the magazine to work with a more conversational tone — and even use GIFs.

This time around, she wanted to do something similar, but on a serialized basis. She decided to use Messenger to follow the four voters because it offered a location where readers could come back to to follow the story, it allowed push notifications, and it was a place that enabled the magazine to work with a more conversational tone — and even use GIFs.

“Our preference was to have a place where the readers were already spending a lot of time. There’s an intimacy of being in between messages from friends and maybe a message to announce a party. It’s a place that’s different, and that helps us tell stories differently,” said Cerdan, who was a 2015 Nieman affiliate.

The Messenger bot is linked to L’Obs’ political Facebook page, which has more than 157,000 followers. The number of people using the bot fluctuates based on factors like number of notifications that it sends and how it’s promoted on L’Obs’ website. Posts on Messenger can’t be shared. “If we don’t really promote it, the numbers don’t grow,” Cerdan said.

The team at L’Obs decided to use bot platform Chatfuel to run the project because it has a fairly straightforward CMS and didn’t require too much technical work.

The team at L’Obs decided to use bot platform Chatfuel to run the project because it has a fairly straightforward CMS and didn’t require too much technical work.

The interface even allowed the journalists to choose how long they wanted the dots that showed someone was “typing” to remain on the screen. Cerdan said the format forced staffers to rethink how they write stories.

“You cannot just take a classic story that you would’ve written and just display it differently,” she said. “You have to think about the structure, the way you want to say it, and the little show-typing thing. You have to acknowledge the rhythm of the reader, also.”

L’Obs found the four participating voters through a variety of methods. It put a call-out on its website and social platforms, but it also reached out to former sources and people who had previously written opinion pieces for the magazine.

It assigned four reporters to the project — one for each participant. The reporters talk with the voters at least once a week, and use those interviews to write the Messenger updates about how the voters’ attitudes toward the campaign have changed, how they’re responding to news developments, and, ultimately, who they plan to vote for.

The weekly updates help to portray how voters are thinking about the election in ways that don’t show up in polling or traditional stories, Cerdan said. The messages are written in a way that makes it feel as if readers are in a conversation with voters. Cerdan hopes the exercise will allow L’Obs readers to understand those who have different political persuasions. (L’Obs leans center-left.)

Some users have tried to reply with their own messages directly to the participants. “What I found interesting, when I found that kind of interaction, was that clearly it felt like they were in a conversation,” Cerdan said. “[The user] was really feeling like he was talking to someone, which is cool. When you have a reader involved in that way, you really feel like you’ve achieved something.”

L’Obs views the Messenger bot as an experiment, and it’s one with a set end date: The first first round of the presidential will be held on April 23, followed by a possible run-off on May 7.

Cerdan said she had to convince her bosses that the experiment was worth trying even though it wouldn’t drive traffic to L’Obs’ website or immediately convert readers to paying subscribers.

But the bot has attracted attention in the newsroom, and Cerdan said reporters are coming to her to suggest different things to cover and other ways to use bots. L’Obs plans to continue to experiment with Messenger and other chat apps.

The next use for the format may be to cover the upcoming trial of Salah Abdeslam, one of the alleged perpetrators of the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris.

“There’s a risk that things won’t unfold the way that we thought they would. A Messenger channel wouldn’t make sense if there’s not something happening every day,” Cerdan said. “But if the trial works in a certain way, you can take the readers to a place that’s interesting in terms of narrative. You can give them a little every day, and avoid asking them to read a long story.”