But squeezing some ideological diversity into readers’ media diets is far from a silver bullet to the problem of misinformation and partisan echo chambers slicing society into isolated realities.

“The idea that you’ll get to truth by, for instance, just reading Breitbart and then Truthout, and somehow will come to truth, is kind of a bizarre idea,” Mike Caulfield said, when I told him about friends who, post-election, have been trying to “balance” out the “liberal bias” in the media they consume.

Caulfield, director of blended and networked learning at Washington State University Vancouver, has worked over the past few months to pilot a claim-checking wiki for college students at the Digital Polarization Initiative (Digipo), which nudges students to consider the online ecosystems from which these claims originate, and also the ecosystems in which they are then more widely discussed. (He explains why the pages are structured the way they are, in depth here.)The wiki houses student submissions of various claims that have made the rounds online, across lots of different fields in addition to politics, from environment to hate speech to race and immigration to psychology and neuroscience. Students from participating institutions work in public, collectively, to fill out the life cycle of the claim and summarize and weight the viewpoints that have been shared online about that claim, a sort of Know Your Meme of viral information.

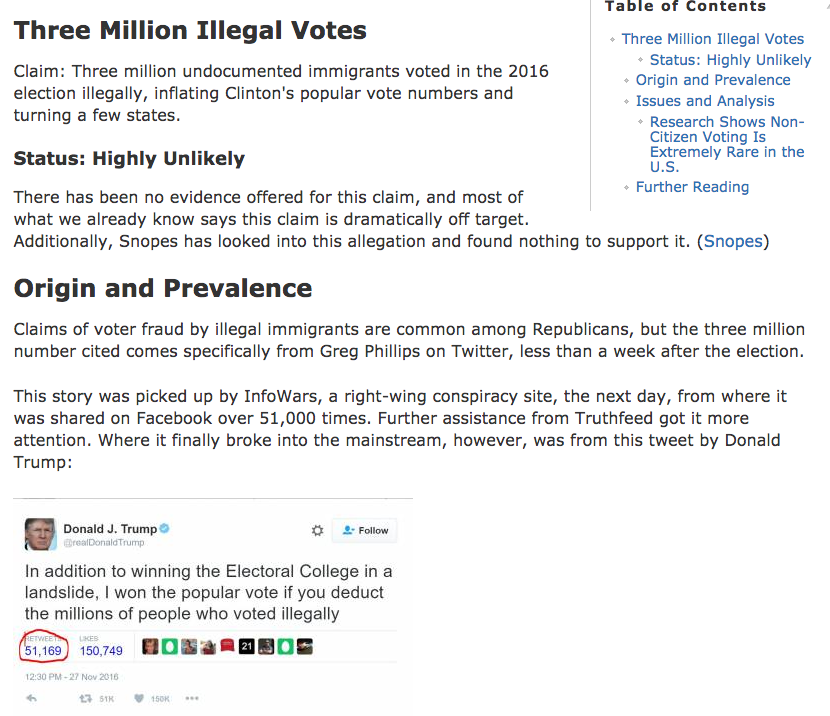

The page on the infamous “three million illegals voted” claim, for instance, includes the following cautious reasoning from students on the veracity of that claim: “There are no good reasons to believe this claim, and numerous reasons to doubt it,” the student editing the wiki page concluded. “The primary reason to doubt it is that zero evidence has been presented. The entire case is a tweet where someone claims to have evidence.” You can also check out the page’s revisions, find a list of sites that spread the original claim, and browse for links to additional analysis on the claim. The voter fraud claim was labeled “highly unlikely” — a designation that could easily be debated through editing the wiki, Caulfield suggested.

“When we’re after truth, our simple definition, for the purposes of the wiki, is that ‘truth’ is something generally believed by people in a position to know, that are likely to tell the truth,” Caulfield said. “But people are getting obsessed with the ‘Are they likely to tell the truth?’ piece of this, without getting into the question of ‘Are they in a position to know?'” (Sites that aggregate and spin someone else’s reporting, or rely on sources who weren’t at an event to weigh on on what happened there? Not in a position to know.)

The wiki is part of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities’ American Democracy Project, started shortly after the November U.S. election; so far, it’s been shared only within the AASCU network, though anyone with a .edu email can register, gearing up for a wider launch in June. Several schools are plugged into the wiki so far, and its use case goes beyond teaching media literacy.

“It’s an idea that fits well into a lot of different classes. You can drop it in a public policy class, you can drop it in a writing class,” Caulfield said. One neuroscience class is using the wiki to address suspect psychological science claims. An environmental class is looking at tensions around water use and contributing factors to drought.

The wiki is linked up with a Hypothesis annotation widget to allow students to point to specific lines from anything they link to to back up their fact checks. The process of writing new pages may feel clunky to students (“the tech for public wikis just feel years behind the times”), and some users write into a Google Doc, which is then ported over into the wiki. The open source DokuWiki software that Digipo runs on is just a temporary solution. Ideally, Caulfield said, he’d find a tech partner that could provide an easier-to-use platform, one that doesn’t necessarily only involve students.

“If other people could build that framework, we could just focus on the pedagogy, getting students to think about this stuff, and people who are much better at the other piece could take care of the technology,” Caulfield said. “We have to come up with something better than Google Docs.”