Three years ago, the Norwegian publisher Amedia, which owns 62 local and regional outlets across the country, introduced a digital subscription strategy, starting with a universal login system across all its newspapers’ platforms it called aID.

And it’s found remarkable success: Since launching in April 2014, the company has signed up about 130,000 digital subscribers — more than any American newspaper aside from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post. That’s in Norway, a country with a population of about 5 million people. (By way of comparison, Gannett — which includes over 100 daily newspapers and operates in the much larger U.S. and U.K. — just announced it had crossed 250,000 paying digital-only subscribers last week.)

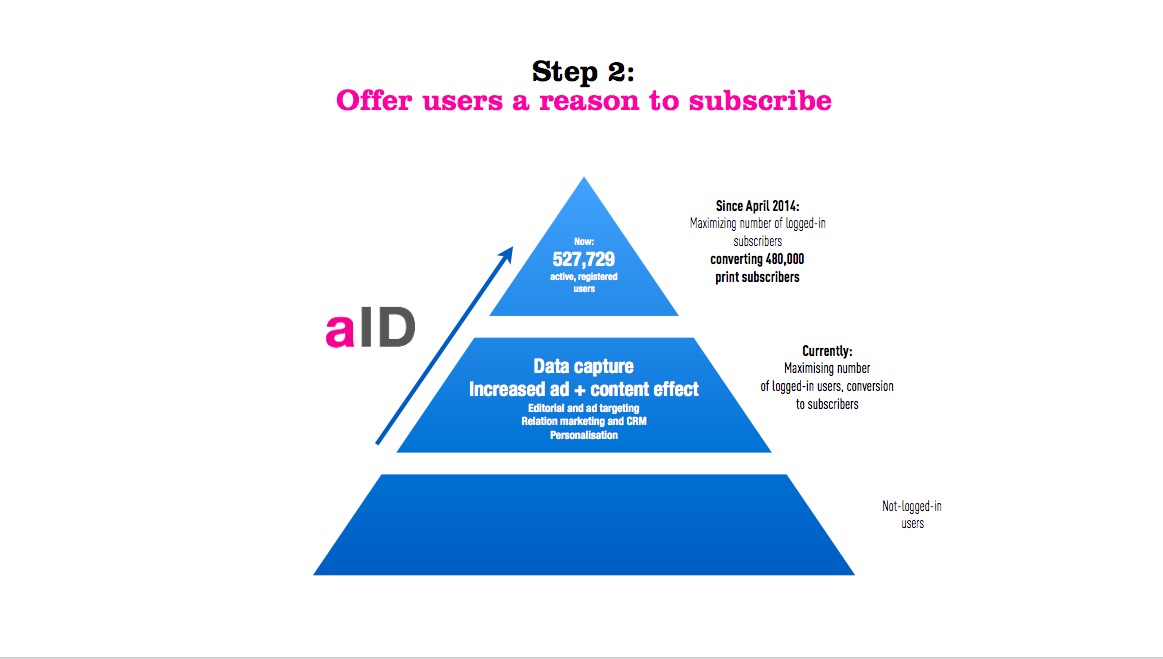

Amedia attributes the growth to a three-pronged strategy addressing three groups of customers: existing print subscribers, those who are registered online users, and those who are use the company’s sites without registering and logging in. In each case, the effort is to move people up the value chain: to get the unregistered to register, to convince the registered to subscribe, and to move print subscribers into digital registration and, eventually, to upsell them into premium products.

Amedia now has about 530,000 total paying users (both digital-only and print-plus-digital) registered in the aID system — about 10 percent of Norway’s entire population. And 800,000 Norwegians are registered on its sites.

Amedia expects the growth to plateau in 15 to 18 months, Pål Nedregotten, the company’s EVP in charge of business development, data/insight and innovation, told me last week at WAN-IFRA’s Digital Media Europe conference in Copenhagen, Denmark. As the company prepares for growth to slow, it’s looking to find new ways to engage its existing audience more deeply. For instance, Amedia bought the rights to lower-level Norwegian soccer leagues and broadcast 347 matches last year.

Amedia made NOK 123 million ($14.3 million U.S.) in profit before taxes last year, a decrease from NOK 267 million ($31.2 million) in 2015. Advertising revenue fell by 16 percent in 2016, and for the first time last year, the company’s subscription revenue surpassed advertising.

Nedregotten gave a presentation about the company’s strategy at the conference. He and I spoke prior to his presentation about Amedia’s use of data, the importance of strong journalism, and what’s next for the company. Here’s a lightly edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

The key to utilize it further is to have a lot of data, so that we’re able to find the right segments to attack with different value propositions. We’re looking at how many visits it takes to register, how few visits it takes before you actually stop subscribing. We’re able to see patterns into which kinds of customers are likely to go to another level. We’re using this kind of insight both from the open-traffic, cookie-based, browser-based customers, all the way up the funnel to our logged-in really valuable customers, looking at what they’re willing to pay more for.

Because we’re a local media company — we have 62 titles scattered all across Norway — we have tested willingness to pay for more than one title, offering access in a region for all the newspapers we have in a region.

[Having 62 sites across the country] certainly made it easier for us, because we had done a lot of investments that we didn’t really have to think about; we had building blocks to stand on when we started out. But it was also understanding the advantages we had in the marketplace and the role we used to play in people’s lives. We wouldn’t have been able to execute if we didn’t have that kind of understanding.

It was starting out with: Okay, we have these 480,000 paying print subscribers. What are we going to do with them — are we just going to allow them to disappear one by one, or are we going to try and make them into digital users? That was the starting point that was rooted in a value that we had and a recognition of that value.

Now we’ve passed 130,000 paying digital subscribers; three years ago, we had zero. In a country with 4.1 million people above the age of 15, these numbers are significant.

When we started out, I’m sure a lot of people were worried about cannibalization, and people moving from print to digital, but that hasn’t really happened at all. We have good numbers to show that people who cancel their print subscription would cancel anyway, and we’re actually now getting them as a win back into the digital subscriptions. We’re putting up a value proposition: If you want the news delivered to your door every single morning, you can get it. If you don’t want that, you don’t have to. Every single print subscriber is also a digital subscriber, so they are getting the digital value and access to all the digital channels that we use, because we radically simplified our product pricing points and the products we offer.

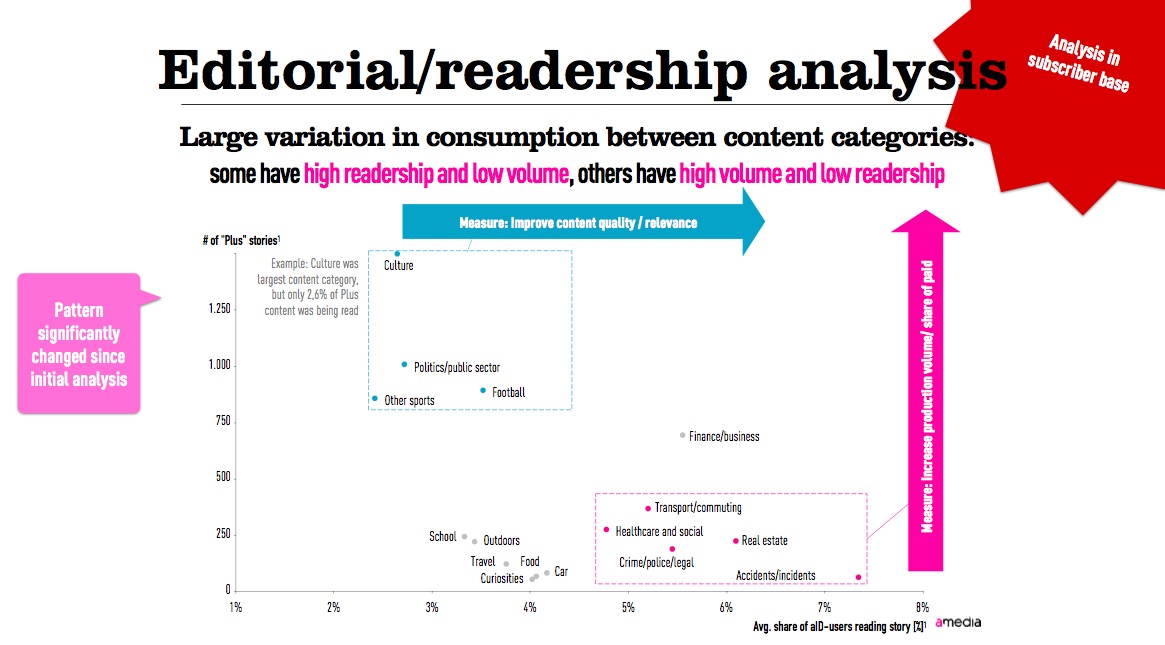

One of the things holding us back in digital was production processes. All of our journalists were producing for templates in a print geometry. They were writing stories to fit the print geometry — because someone said many years ago that you should have four pages of culture, not withstanding the fact that you probably didn’t have four culture stories to print that day. When you just put those things online, no wonder nobody clicked on it or read it — it wasn’t that interesting. When we changed our production flow and our journalists started actually writing for our digital platforms and the digital tool first, that improved massively the quality of journalism that we were publishing in the print papers as well.

We started going for the more engaged readers, the people who actually had a relationship with the communities where we published. That, after an initial settling-in phase, translated into higher pageviews.

There were a whole host of legal issues that we had to learn how to deal with. It’s also been a journey not just for the journalists, but for our sales guys, the administrative staff, the top management, pretty much for the entire organization.

Engaged readers are far better customers. They remain subscribers. It’s all about working smarter and being able to offer a better value for our subscribers. That’s probably never going to stop.