Last summer, Canadian tennis player Milos Raonic made it all the way to the men’s singles final at Wimbledon, beating Roger Federer in the semifinal before succumbing to Andy Murray in the championship match.

One of the possible reasons for his success? Additional coaching from American tennis great John McEnroe who started working with Raonic for the grass court season last year.

But McEnroe also works as a tennis analyst for the BBC and ESPN, calling Raonic’s matches for both networks.

“If F. Scott Fitzgerald were covering tennis, he’d note that the rules for John McEnroe are different than for you and me,” Sports Illustrated media reporter Richard Deitsch wrote last year.

Though McEnroe ultimately stopped working with Raonic ahead of the U.S. Open last year, the tight-knit nature of the tennis world has led to numerous complaints of conflicts of interest, along with increased media consolidation. In March, Sinclair Broadcasting Group, which owns the Tennis Channel, bought Tennis magazine and Tennis.com.

“The challenge, and really the opportunity, is disrupting this market, which in our sport in particular is so newly consolidated but always has been about access and exchange for softballs,” said Caitlin Thompson, publisher of Racquet magazine.

“Former coaches are the people who commentate, and the columnists are married to the agents who represent the players,” she continued. “I think this happens a lot in sports anyway, but there’s almost no journalism in tennis. That’s what I have concluded. Then these two big, huge entities — kind of the only two big ones in the States, but truly in the world, between Tennis Magazine and Tennis Channel — when they combined forces, it was just: Man, nobody is going to say anything interesting about this sport.”

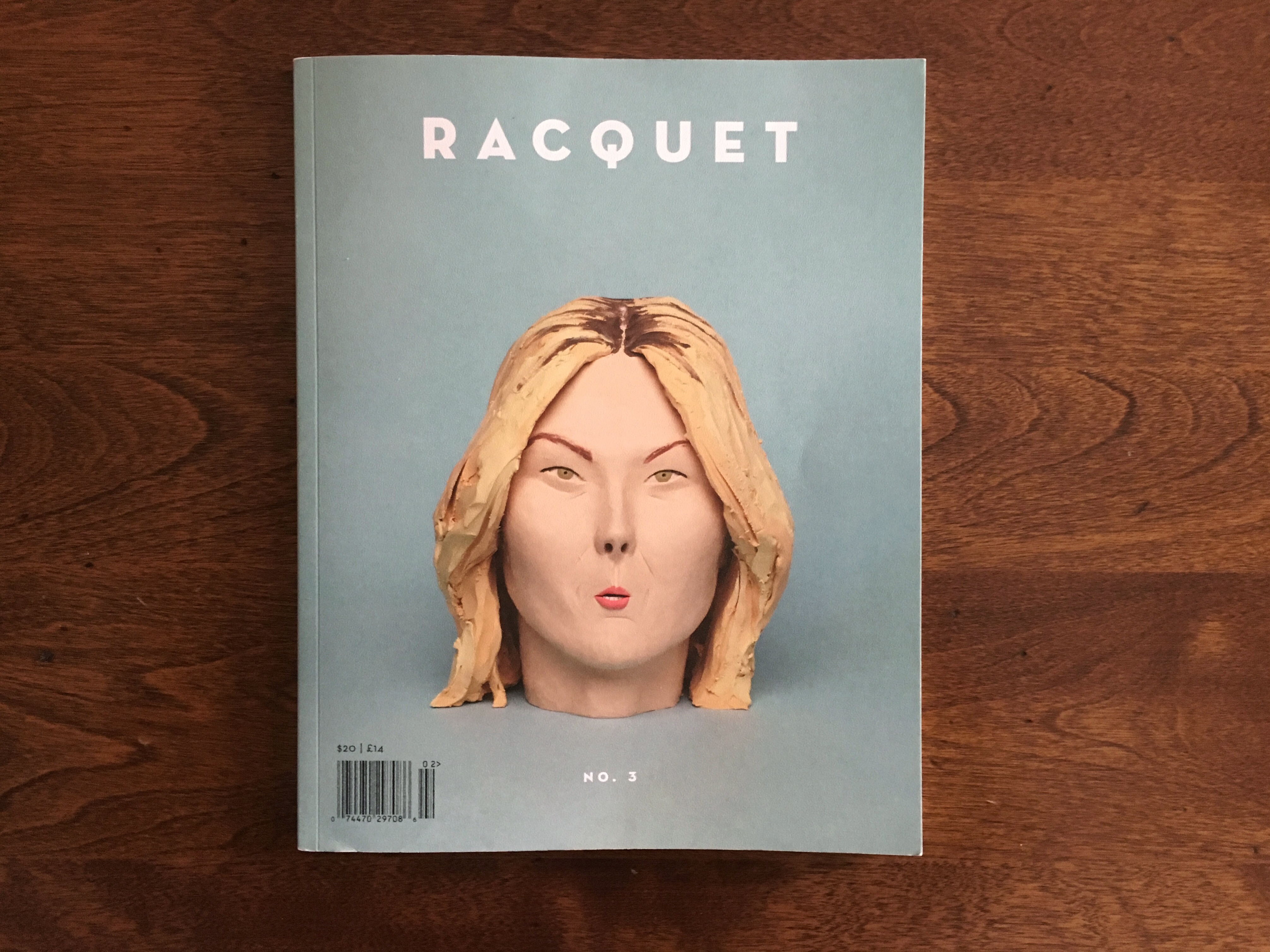

Racquet is a quarterly print magazine covering tennis that aims to provide that independent voice that Thompson says the sport lacks. The magazine was launched as a Kickstarter project by Thompson and editor David Shaftel last year, raising $55,000. Racquet published its third issue this spring with a cover story focusing on controversial star Maria Sharapova, who was suspended for 15 months for testing positive for a banned substance.

“You don’t have to know about tennis to find this interesting, and if you know anything about tennis you maybe would have read a story like this 10, 15, certainly 20 years ago,” Thompson said. “Now there’s zero chance that you can read anything remotely critical of her. Now all the tournaments are rushing to put her up on their sites.” (Though this week, she was denied a wildcard spot in the French Open.)

“It’s like when A-Rod came back and there was actual discussion and scrutiny,” Thompson said, referencing former baseball player Alex Rodriguez’s year-long suspension for using performance-enhancing drugs. “I actually think the media gave him too much of a hard time. But at least the dialogue was had, and that is just not something that anybody in the tennis world is interesting in talking about.”

The internet has enabled an explosion of online-first sports media brands for virtually every team and sport — from SB Nation’s dozens of blogs to Bleacher Report’s seemingly endlessly customizable push alerts on the TeamStream app — that give you up-to-the-minute details on anything you could possibly want to know. But contrary to that trend, there’s also been a growth of slow, high-quality print magazines such as Racquet. There’s Howler and Eight by Eight, which both cover soccer, and Victory Journal, a self-proclaimed “journal of sport and culture.”When a new issue of Racquet comes out, Thompson said, she wants people to think “they’ve been hard at work and now they’re back with something essential.” The internet, she said, “has stopped feeling essential to me.”

Recent stories range from a look at the technology used at the USTA’s national training center and a profile of former Russian president Boris Yeltsin’s tennis coach to an original work of tennis-centered fiction.

Racquet also holds events, publishes a regular newsletter, maintains an active social media presence, and has a podcast. (Thompson’s day job is director of content for the Swedish podcasting company Acast.) Racquet is also interested in creating documentaries, books, or even live podcast shows.Thompson said print is the heart of what Racquet produces, even as it sees digital platforms as a way to share some of its work and stay connected to the sport between issues. Its recent Sharapova cover story, for instance, was co-published with Longreads. But the magazine’s digital strategy has been an outgrowth of how Thompson and Shaftel were already talking about tennis online.

“Because it’s quarterly, it’s less of a way to get content distributed through channels…I’m going to be on Twitter anyway talking about tennis — I might as well be doing it through the Racquet account. David would be sending me photos of Andre Agassi’s butt in spandex from 1992, so he might as well put it on the Instagram account, which are both 100 percent true things that happened,” Thompson said. “We are in this world and we love it. We were doing it before we had a magazine and that is why we have bent the digital strategy to be part of the magazine’s effort. I would be lying to you if I said I didn’t have huge ambitions for this — especially after I have a little bit of a messiah complex now about how we have to save tennis from itself.”

While Racquet has been praised in publications such as The New York Times’ T Magazine and Monocle, it’s been more of a challenge to break through to the tennis world, Thompson said.

“I thought we would be less of a hit in the indie magazine scene and more of a hit in the tennis scene,” Thompson said. “What that makes me think is that the tennis scene still doesn’t understand us and the indie magazine scene wants us to go even further. It’s changed our strategy a lot, which is to say: bigger, bolder, more thorough.”

The magazine has about 2,000 subscribers, Thompson said. An annual subscription costs $84; individual issues are $20.

Racquet needs to hit about 2,500 subscribers to break even if it’s being “very unambitious,” Thompson said, but its goal is to reach 8,000 subscribers in order for it to be truly sustainable and to be able to continue to grow its coverage.

The magazine began as a side project, but Shaftel has begun focusing more of his time on it and Thompson said they are looking to hire someone to handle more of the business operations. Still, the magazine is also committed to remaining independent, Thompson said. The magazine has limited newsstand distribution and does sell ads and merchandise, but subscriptions will be the key to the magazine’s sustainability.

“Subscription is really truly the lifeblood. And thinking about it like podcasts, because that’s where the other half of my brain is living, you could have the greatest episode in the world, but if you don’t have a subscriber base, it kind of doesn’t matter,” Thompson said. “We’re trying to figure out how to get those subscribers. We had initially ignored tennis clubs. I just spent a lot of time telling you about the tennis establishment, but I think recreational players are a little different from the tennis establishment, and those are people we’re going after now.”

Now that tennis season is in full swing — the French Open and Wimbledon are fast approaching — Racquet is hopeful it will be able to grow its readership as well as interest in the sport.

“I’m targeting the people who are into the Wes Anderson–Bjorn Borg aesthetic,” Thompson said.