When you’re reporting on a trip through four continents with countless dialects and local guides along the way — how on earth do you communicate with people both for interviews and for sharing the stories?

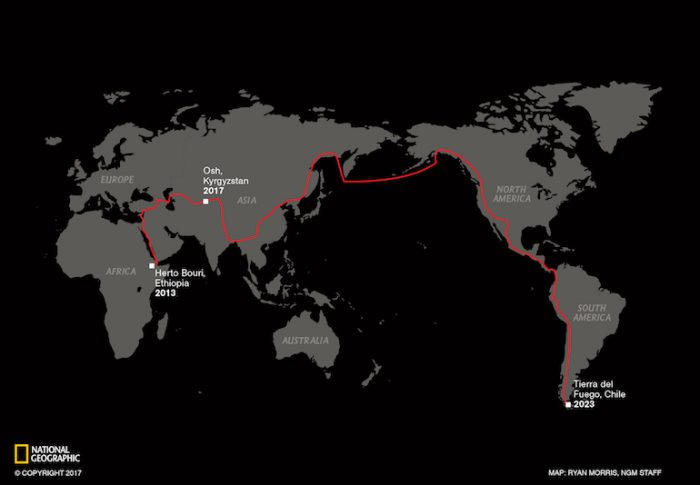

That’s something that former Visiting Nieman Fellow Paul Salopek is trying to find out, as he has been literally walking across Earth for the past four years in a project called the Out of Eden Walk. Chronicling the global migration of humanity step by step, from the basin of Kenya to the sacred lands of Israel and the West Bank, to, currently, the Pamir mountains of Tajikistan, Salopek is in the midst of a multi-year journey that started in 2013 and is scheduled to conclude in the Patagonia region of South America in 2023.“We want to share the storytelling with the people whose lives I am walking through,” Salopek explained in an email from Tajikistan, “where flying ants attracted by my headlamp are rocketing up my nose.”

Logistical obstacles aside, Salopek and the Out of Eden team — the project is led by National Geographic and has support from the Knight Foundation (which also supports Nieman Lab ) — have recently been exploring the digital challenges and opportunities that modern technology has developed. These include condensing his reporting backpacks into the latest iPhones and also building out software for a community of volunteer translators to share Salopek’s stories in languages across the world. This translator tool has since allowed the 20-plus volunteers to publish more than 200 translations across 16 languages (the tool currently supports 26 languages).“We have seen strong representation of languages prevalent in the regions Paul has walked through and written about in his dispatches from the field — Russian, Arabic, and Turkish, for example,” said National Geographic intern Andrea Vale. “But at the same time, some of our most prolific translators are working in languages with little direct geographic connection to the walk route — Polish, Kannada.”

The Out of Eden team examined existing software to adapt for the tool, but decided to build its own interface and user experience to fit with the longform narrative nature of the project and its varying audiences. “Both the translation effort itself and the community aspect are important objectives of the tool,” Kasie Coccaro, the director of impact initiatives at the National Geographic Society, said. “We hope this will continue to grow and become a valuable forum for some of the project’s most ardent followers to connect with one another, trade ideas, and share their enthusiasm for the walk’s mission.”

Salopek shared some of his thoughts on the necessity of the translation ability and provided an update from the field — or rather, from the mountains of Tajikistan. (You can see where he is in real-time here.)

Thankfully, my main distribution partner, the National Geographic Society, has supported this global experiment. We’ve stayed true to the “slow journalism” ethos of the walk, a literary style of reportage that strives to grow attention spans online, rather than shrink them through microblogging, etc. We ask readers to wait. The reward, hopefully, is storytelling that evokes some nuanced sense of wonder at our shared world.

I started out in Ethiopia completely against social media as an interactive or promotional tool. I thought it would be too intrusive for my process, which is solitary. But as you’ll see, we have an active presence on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. It became clear early on that this was an organic way to sort of subvert the shallowness of the medium, by maintain an interlinked, lyric heartbeat for a project that — again, by design — produces meatier dispatches only every week or two. I’m lucky to have a wise social media editor, Camille Bromley, to manage that. And the social media interactivity with readers has turned out to be a pure delight — and sometimes a good source of stories.

On the non-digital front, a long, immersive project like this one that rambles through dozens of cultures and languages benefits, too, from in-person interactions. I lecture at schools along the way, offer free journalism workshops to colleagues in the countries I walk through, open museum exhibits, do media appearances, and otherwise engage in public diplomacy for the journey. Somewhere in there I also have to walk and write. A lot. Like right now, at night in the Pamir mountains of Tajikistan, where flying ants attracted by my headlamp are rocketing up my nose.

But like everyone else who uses this technology, I’ve seen the dystopian side, too, at foot level. I was detained by security forces 34 times in Uzbekistan. It wasn’t the secret police who were stalking me for walking while being foreign. It was ordinary people calling the cops because they’d been indoctrinated from kindergarten to report alien-looking people. Digital technology deployed in infantilizing cultures of fear. Sounds like it’s a spreading phenomenon.