Newsrooms’ well-worn refrain about their audiences — we need to meet them where they are — means something more urgent in the middle of a category five hurricane.

Where are the shelters? Where can I get water and food? Where is the storm now?

Univision Nathalie Alvaray, Univision’s manager of local digital news, and four other newsroom colleagues began sending out brief but constant bulletins to a WhatsApp group Alvaray created to field questions around Hurricane Irma as it was bearing down on Miami — where major Univision studios and business operations are based — after destroying parts of the Caribbean (Here’s an overview on how Univsion as a whole reported through Irma.)

WhatsApp is barely used for news by the general U.S. population; just 3 percent of U.S. adults surveyed in the 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News report have used it to share or discuss news. But it reigns among mobile apps throughout Latin America (and, well, most of the rest of the world, too).

“WhatsApp is the closest tool people have in their hands. They trust what they receive from friends and family there, they share, they consume everything, and since all newsrooms are saying we have to be where audiences are, we all thought, we have to be on WhatsApp,” Alvaray said. “I’ve been thinking about this a lot as an immigrant from Venezuela. I share experiences with my family and friends through WhatsApp groups — I myself juggle 17 or more groups on my phone.”

Alvaray, holed up at a hotel with her family before Irma made landfall in Florida, monitored all the updates Univision reporters were putting out online, and at the same time was feeding these updates to her personal groups on WhatsApp.

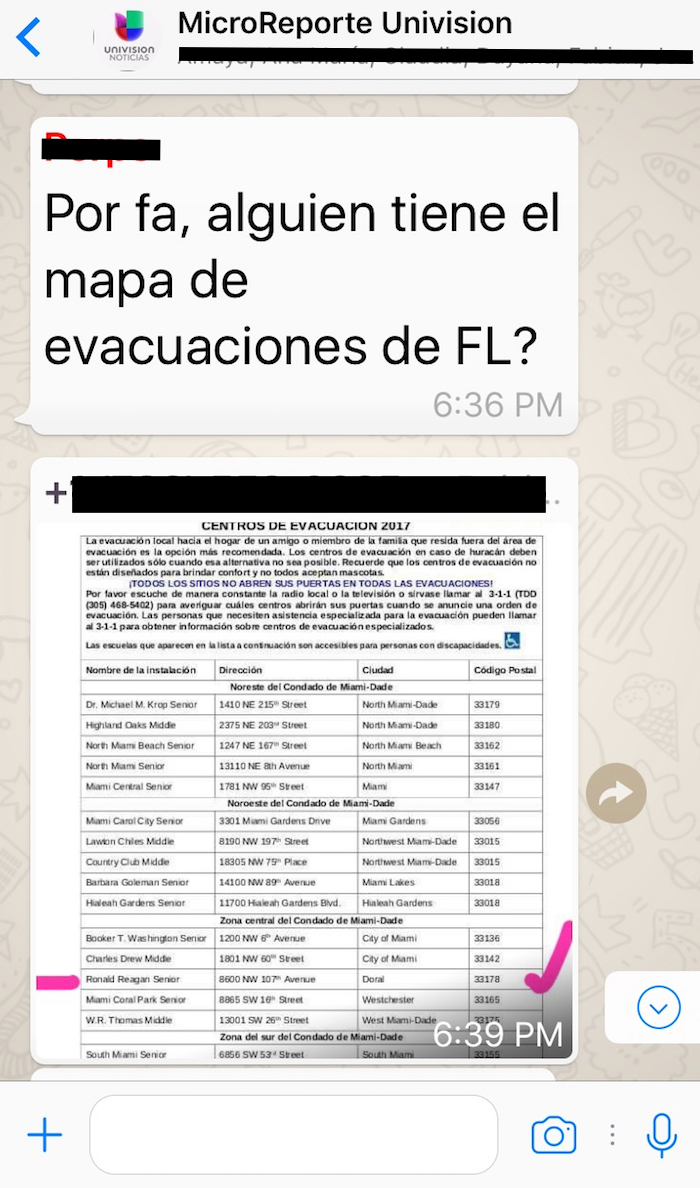

So she started putting Hurricane Irma information onto shareable social cards in Spanish, distributing them, among other places, on a new official WhatsApp group, every two hours. Several more colleagues, also working remotely away from the newsroom, joined the distribution efforts. Group members asked questions beyond what was reported in the shareable bulletins from Univision. Which roads were still open? Where could people get gas? Members asked about shelters in specific parts of the state they didn’t see on Univision’s map; Alvaray informed the newsroom, and sent an updated link to the map to the group. The group also took on a life of its own — two neighbors found each other in the group, and others shared their own news links and updates. She knew their experiment was gaining traction, she said, when she saw her personal networks on WhatsApp also circulating Univision’s news bulletin cards.

So she started putting Hurricane Irma information onto shareable social cards in Spanish, distributing them, among other places, on a new official WhatsApp group, every two hours. Several more colleagues, also working remotely away from the newsroom, joined the distribution efforts. Group members asked questions beyond what was reported in the shareable bulletins from Univision. Which roads were still open? Where could people get gas? Members asked about shelters in specific parts of the state they didn’t see on Univision’s map; Alvaray informed the newsroom, and sent an updated link to the map to the group. The group also took on a life of its own — two neighbors found each other in the group, and others shared their own news links and updates. She knew their experiment was gaining traction, she said, when she saw her personal networks on WhatsApp also circulating Univision’s news bulletin cards.

“The key is to keep it very brief and very factual and very useful, in order to declutter the conversation,” she said.

The first WhatsApp group quickly hit the limit of 256 members. Univision tried to get WhatsApp to waive the limit for this group but was unsuccessful, so Alvaray and colleagues had to spin up and manage a second, separate group.

The team stopped at the second WhatsApp group, because Alvaray and colleagues realized they themselves were about to lose power on Sunday as Irma passed southwest Florida and wouldn’t be able to continue the experiment. The idea had been to simply open as many groups as they could to share information — “with five of us, we could each handle at least two,” Alvaray suggests. Other outlets have attempted delivering news to WhatsApp at scale, and the volume of messages across multiple groups can make for a logistical nightmare. (WhatsApp announced earlier this month that it plans to launch a product for businesses that may help; some businesses will have to pay to use it.)WhatsApp presents other challenges when it comes to broadcasting this way.

“You have to listen and take care of your community, which is very active. You cannot delete posts. You have to set rules so people don’t share commercial information or political information or other inappropriate communications,” Alvaray said. “I truly wish we could work with WhatsApp to open up this group.” But it’s applying some insights from its experiment during Irma to new WhatsApp groups dedicated to the new Hurricane Maria as the storm makes landfall in Puerto Rico Wednesday morning.

#HuracánMaría: estos son los números de emergencia que debes tener a la mano en #PuertoRico. pic.twitter.com/K6moV5ErqV

— Univision Noticias (@UniNoticias) September 18, 2017

“We were scarce on resources during Irma because we were outside the newsroom, and we were in it,” Alvaray added. For Hurricane Maria, she’ll actually be in the Univision newsroom. “Now we can allocate more resources to monitoring the conversation more closely. I also want to try some things with audio content, which is popular on WhatsApp — so some reports every hour, that could read two or three facts that you need to know at this time.”