How much news is really in Facebook’s “News” Feed? What sort of posts do people see when they quickly check Facebook in bed in the morning, when they peek at it in line for lunch, when they scroll through while on the toilet (let’s all be honest with each other here)?

The answer is different from person to person, and influenced by any number of muddy variables. The makeup of a person’s feed might depend on the device they’re using. Whether they like a lot of news organizations’ pages. Whether they ever click on this news article link or watch that news video. Whether they’re on wifi or using data, checking in the morning or the evening. Whether their Facebook friends shared and discussed the news. Whether those news outlets have fast-loading pages. Whether they’ve “snoozed” groups, friends, or pages (a feature Facebook is rolling out this week). What you count as “news.”

Still, I wanted to get closer to a portrait of an “regular” Facebook feed — that is, the feed of someone who doesn’t follow Nieman Lab on Twitter.

So I surveyed the Facebook habits of, and got real News Feed samples from, 402 people ages 18 or older in the United States. I reached them using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform between Oct. 31 and Nov. 3, asking them to send me screenshots of the first 10 posts in their Facebook feeds. (I was the only person to see the images, and used them for classification purposes only. No identifying information is referenced in this story.)

The findings were remarkable, given how large Facebook looms in news industry discussions about our disrupted present and future:

Half the people in our survey saw no news at all in the first 10 posts — even using an extremely generous definition of “news” (from celebrity gossip to sports scores to history-based explainers, across all mediums; our count included any news shared by the publishers themselves, other pages, or individuals, and sponsored publisher content).

Another 23 percent saw only one piece of news content. Sixteen percent saw two. Exactly one person out of 402 had news stories make up the majority of their feed (eight news items).

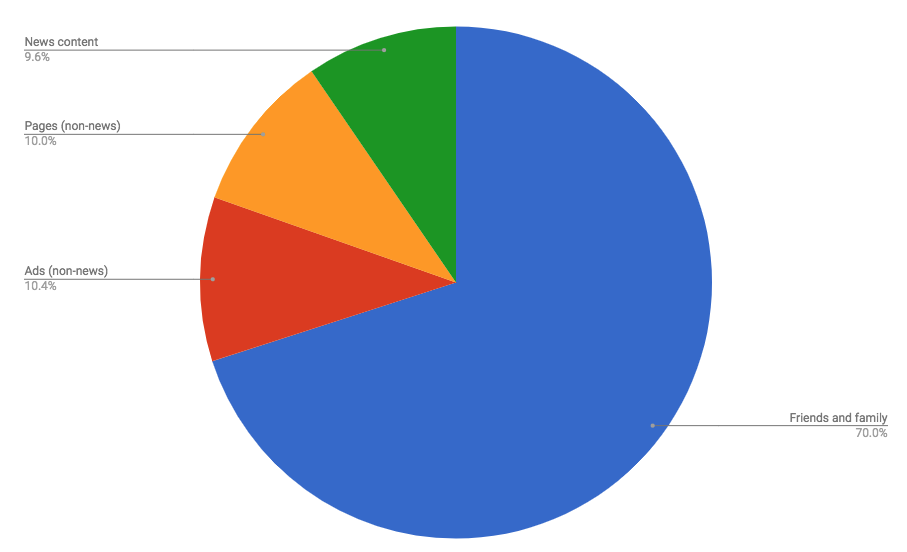

Of the 384 total news-related posts that surfaced in my sample, half were shared by someone other than the original publisher, whether by friends or a non-news page (e.g., by a friend in a Deplorables Facebook group, or by a Buffalo Bills fan page). Only 4 percent of the news posts in our sample came directly from publishers, though the range of publishers represented was pretty wide. Non-news ads and non-news posts from non-news pages made up the rest of the 4,020 total posts in our sample. (There were no Instant Articles at all, but most respondents accessed Facebook on desktop for this project.)

In this experiment, “news” wasn’t just the latest Trump story. It encompassed everything from Facebook-only town-specific news and information pages, to pages dedicated to news about a specific MTV show, to lifestyle stories, to sports scores, to op-ed and analysis pieces responding to news events. Fact-checking posts from Snopes or PolitiFact counted as news. So did a Vox video from 2016 on supersonic flight that someone was re-recirculating; so did a timely iPhone X product review.

I also counted stories shared by partisan outlets such as Breitbart News and LifeZette; both these outlets’ posts cited other reporting. I counted one Gateway Pundit story as news (it wasn’t false). BuzzFeed — to be distinguished from BuzzFeed News — posts that were simply reposts of memes (e.g. “tag your best friend”), BuzzFeed Nifty videos, and BuzzFeed Tasty recipe videos didn’t count. For consistency, this meant I didn’t count a New York Times Food recipe video as “news,” either. I didn’t include explicit satire (e.g., The Onion, The Borowitz Report), late-night talk show bits with celebrities (e.g., Ariana Grande doing impressions), or daytime talk show segments (e.g., Dr. Phil analyzing a couple’s marriage). I did count one investigative segment from John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight and two newsworthy posts from Trevor Noah’s Daily Show (an interview with Hillary Clinton, and a clip on gun deaths in America).

I judged each piece of content individually; no news outlet got an across-the-board classification as “news.” Some of you will disagree with how I chose to classify certain items. You can view the raw data here. A full description of the methodology is included with that spreadsheet. (I only asked for the first 10 posts in part because some research suggests a drop-off in engagement after the first 10 posts; also I am just one person, hand-coding 4,020 posts.)

Only one piece with a false headline — one appealing to liberal sensibilities — showed up in our sample. Most of the obviously partisan stuff appeared not in news posts, but in the statuses of friends and family (to paraphrase two representative statuses I saw: “Can we impeach this guy for stupidity?” “If you’re sitting for the national anthem, you don’t deserve to stand again”).

During the period of our survey, two major events received significant national attention: The Houston Astros won the World Series, and a terrorist attack in New York City left eight people dead and 11 injured. Three World Series stories surfaced in our sample. Only one story about the terrorist attack did, shared from a Facebook page in support of Ted Cruz.

The potential reach of any given post on Facebook is vast. A quick scan of headlines can lead us to assume that most people’s Facebook feeds are an endless stream of partisan page posts and mainstream news links, jostling for attention. It’s true that a lot of people are getting some news on Facebook: Earlier this year, Pew found that 67 percent of Americans get at least some news on social media, the biggest source being Facebook. And, yes, some 80,000 inflammatory Russia-linked posts reached around 126 million people on Facebook. 126 million! That’s more than a third of the total population of the U.S.

It may be that millions of people see certain news posts. But what’s filling the rest of their feeds is very likely less news than we, the industry that produces the news stories, like to think. After all, Facebook isn’t exactly hiding the fact that in the news feed, family and friends and sharing come first.

Depends, on Facebook ranking makes it so more people see your posts than would otherwise. Without ranking page content would take over most people’s feeds and drown out stories from their friends.

— Adam Mosseri (@mosseri) December 16, 2017

Had I tried to extrapolate from my own feed, I would’ve concluded that all anyone ever sees is news. For 10 consecutive days this fall, I recorded what I saw on my own Facebook news feed in the morning and evening. I found that in that time, most of my feed was news, and about a third of it was consistently news video. Then again, I “like” more than 70 news organizations’ Facebook pages and rarely use Facebook to engage with friends or family. (But it’s a worthwhile remembering that journalists’ experience of Facebook isn’t necessarily similar to our readers’.)

My Nieman Lab colleagues, meanwhile, see virtually no news in their feeds, and only when it’s shared by friends. This also appeared to be closer to the experience of the people who tweeted at and wrote to me.

Sarah Schmalbach of The Guardian’s Mobile Innovation Lab sampled her feed back in October 2016 and reported that it was around half news. A spot-check of her non-journalist friend’s feed revealed it to be about 40 percent news. Facebook’s algorithm may have changed since then, or the two may be outliers.

We’d love to know what you see in your feed! Let us know in the comments, email us (staff@niemanlab.org), tweet at us, or send us a Facebook message.

I presented Facebook with my findings and asked for hints about what signals might be contributing to my all-news Facebook feed versus my study participants’ — and my colleagues’ — news-lite feeds. Facebook, of course, doesn’t want people gaming the system; moreover, it doesn’t know all the levers that users themselves might be pulling, by starring pages, hiding posts, or unfollowing certain people. A spokesperson passed along a statement and pointed to various efforts the company has made in the past year to wring out misinformation.

Everyone’s News Feed is unique, each based on a range of signals people who use Facebook tell us about themselves, including the things to which they react, what they choose to share, their friends, and other signals. We use those signals that people on Facebook produce to deprioritize content that is inauthentic, including hoaxes and misinformation — and to prioritize things that people signal to us as more relevant to them.

Facebook has immense power over the news industry — hosting our stories, delivering the readers, facilitating spaces for those readers to gather, encouraging us to spin up Facebook groups, and incentivizing us to make awkward live video and now, longer video, and video tailored for commercial breaks (sorry, “midroll” ads). Just last week, Facebook confirmed it wouldn’t renew contracts with the publishers and celebrities it had paid to make all that live video. It also introduced News Feed tweaks to account for videos distributed by pages that have more loyal viewers, and trials for ads that would run before a video starts in its dedicated Watch section.

How news organizations behave on Facebook, for better or for worse, is intertwined with the strategy decisions of Facebook as a company. The downward swings in reach that result from a change in the News Feed algorithm can be dramatic. This past April, a Chicago Tribune editor shared some data that showed the Tribune’s total number of followers had grown, but the average reach for posts had plummeted since January. Other media companies began reporting the same. Social media managers for news organizations had the sneaking sense that Facebook declined as a source of referral traffic this year, and now the data bears that out: Facebook drove about 40 percent of publishers’ outside traffic in January, and that number has declined over the past year to 26 percent, according to Parse.ly analysis.The News Feed development that’s arguably shaken our industry most this year, however, was the test Facebook started in late October in six countries that broke out posts from pages into a separate, less visible “Explore” feed. It set off panic that such a move would destroy news organizations that rely on Facebook to reach audiences, not to mention end up doing serious harm to the test countries’ political stability. What if that disruptive test rolled out permanently to the rest of the world, exiling news from the News Feed for good? (Facebook News Feed VP Adam Mosseri has said there are no present plans to do this.)

My experiment looked at only a sliver of the Facebook user base. But, in a group where a majority say they’ve checked Facebook for news, news didn’t rise to the top of what they saw. Even if news pages are never officially separated from the News Feed, I wonder whether through users’ behaviors or Facebook’s desire to cater to those preferences or the feedback loop of both, news content is already barely clinging to the fringes of a feed that’s “news” in name only.

The people who responded to my study via MTurk aren’t representative of the general American population, but they are certainly more varied in age and online habits than a collection of wonky media people. The MTurk user base overall is likely younger and more educated than the average American workforce. They’re also self-selecting in that they responded to a task described as a “study of news content in the Facebook News Feed,” but that worked for my purposes since I was only interested in the people who consume content online, news or otherwise. (Which they do: Three quarters of the people who responded to our study said they’ve checked Facebook for news. You can find additional details on the demographics of my sample, such as age, political leaning, and news habits, at the bottom of this story.)

This was a U.S.-only look at Facebook feeds. There’s no doubt individuals’ feeds look different in countries where the Explore Feed test is ongoing, in countries where Facebook has subsumed the internet by offering certain sites for no data cost through its internet.org service, in countries with much larger populations than the U.S., in countries where the Facebook user base is very low, and so on.

We didn’t ask people to scroll beyond the tenth post on their Facebook feeds. It’s possible, I suppose, that all that news content is just buried below post number 10.

While it was obvious for some, I wasn’t able to track for all screenshots whether they came from a device or from desktop — people shrunk their images, stretched them, and did all sorts of other weird things to image resolution when uploading. Because our survey respondents were using MTurk, they were likely on desktop computers, and I’m guessing most sent in screenshots of their desktop Facebook feeds, but I can’t be certain.

The categories I used to classify News Feed posts for each person in our sample aren’t precise. I didn’t look at Facebook Groups, which Facebook has prioritized, counting any time a person posted in a Facebook group as a “friends/family post.” On one occasion, Facebook suggested a user follow a brand page, which I filed under “non-news page.” I didn’t break down the friends/family category further either, noting only when I saw a video being shared.

The presence of local news in feeds, particularly local TV news, stood out to me. I didn’t have enough information to drill down further. While declining as a source of news, TV is still dominant. Given the rollbacks of local studio ownership rules, broadcast ownership rules, and most recently of net neutrality, I wonder how these moving pieces will play out on Facebook.

In this particular experiment I didn’t look at relationships between variables, for instance, whether people who followed a lot of news pages also self-identified as more liberal. We collected demographic data in ranges, which makes that analysis difficult. Two specific characteristics seemed to be correlated to seeing slightly more news in the news feed: Liking 10+ news pages, and self-identifying as “very liberal.” But overall, number of news pages followed or self-reported political leanings wasn’t significantly correlated to the amount of news people saw in their feeds.

We didn’t want people to self-report how much news they were seeing in their feeds, because people likely over-report their own exposure to news. But other information we asked for was self-reported, so take it with the usual caveats.

— 94 percent of our group were under the age of 50. More than 50 percent were between ages 18 and 29.

— Overall, they were a left-leaning bunch. 49 percent characterized their political views as “liberal” or “very liberal.” Three percent saw themselves as “very conservative.”

— 80 percent reported having 700 friends or fewer on Facebook.

— 85 percent of the people we surveyed said they check Facebook at least “a few times” each day; more than 40 percent said they checked Facebook “very frequently.”

— Most “liked” only a handful of publishers on Facebook. 59 percent said they “liked” between one and five news organizations.

— More than 75 percent said they ever check Facebook to get news.

— 83 percent at least “sometimes” checked the news outside of Facebook (41 percent said they do that “often”).

— 66 percent said they usually access Facebook on their phones.

We reached users through TurkPrime, a platform that hooks into Amazon’s MTurk, and returns batches of responses (basically, it was a little cheaper), spread out over several days, so not everyone was completing the task when it was released on the first day. We asked respondents nine multiple choice questions through a SurveyMonkey survey. Choices were offered as ranges, so that we weren’t asking people to check their Facebook and individually count, for instance, the number of news organizations they’d “liked.”

We also asked them to link to private Imgur uploads of screenshots of the first 10 posts each respondent saw in their Facebook feed. For this study we only had access to the basic level of SurveyMonkey and MTurk, so there was no built-in image upload option.

We paid respondents 40 cents each for the survey, plus the screenshots. About the same number of completed surveys came in each day it remained live. I initially requested 500 responses, but 78 responses ended up being unusable (respondents didn’t properly upload screenshots, or they weren’t viewable; they marked themselves as not from the U.S. though I set an IP-address requirement. 20 more didn’t complete all the survey questions, because I’d forgotten to mark one of the questions as mandatory).

The survey asked for age; country where they were checking Facebook from (there was an IP-address restriction already, but we included this extra step); number of friends on Facebook; frequency with which respondents checked Facebook each day; whether respondents checked Facebook specifically to get news (news was defined as “information about events and issues that involve more than just friends or family”); the number of news organizations a respondent had “liked” on Facebook; the device they used to access Facebook; how often a respondent either read, watched, or listened to the news outside of Facebook; and self-described political views (very liberal, liberal, moderate, conservative or very conservative). I based the wording of the questions on Pew Research and Reuters Institute surveys. Choices were offered as ranges (I ran a 30-person trial survey with open fields before the current study, and found people filled in numbers at random: e.g. “I check Facebook 999,999 times a day”).

It was really hard to decide whether or not certain posts should count as news. I cross-referenced other studies from Pew Research, the Reuters Institute, Columbia Journalism Review, and BuzzFeed News, in which the researchers also made decisions on what counted as news organizations.

Big thanks to Sarah Schmalbach of the Guardian Mobile Innovation Lab and Kim Sheehan of the University of Oregon. Additional help from Vinay Nagaraju and Samantha Henry of Harvard’s Kennedy School, who borrowed my data in a final paper for her statistics class, and Dylan Lake. Thanks to Paul Hitlin, Grzegorz Piechota, Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, and Amy Webb for additional advice.