From skimming and scanning to (the ultimate) reading, a new paper by Nir Grinberg looks at the ways we read online and introduces a novel measure for predicting how long readers will stick with an article.

Grinberg, a research fellow at the Harvard Institute for Quantitative Social Science jointly with the Northeastern’s Lazer Lab, looked at Chartbeat data for seven different publishers’ sites — a dataset of more than 7.7 million pageviews, on both mobile and desktop, of 66,821 news articles from the sites. (To protect the publishers’ privacy, they aren’t named in the paper, but Grinberg looked at a financial news site, a how-to site, a tech news site, a science news site, a site aimed at women, a sports site, and a magazine site.)

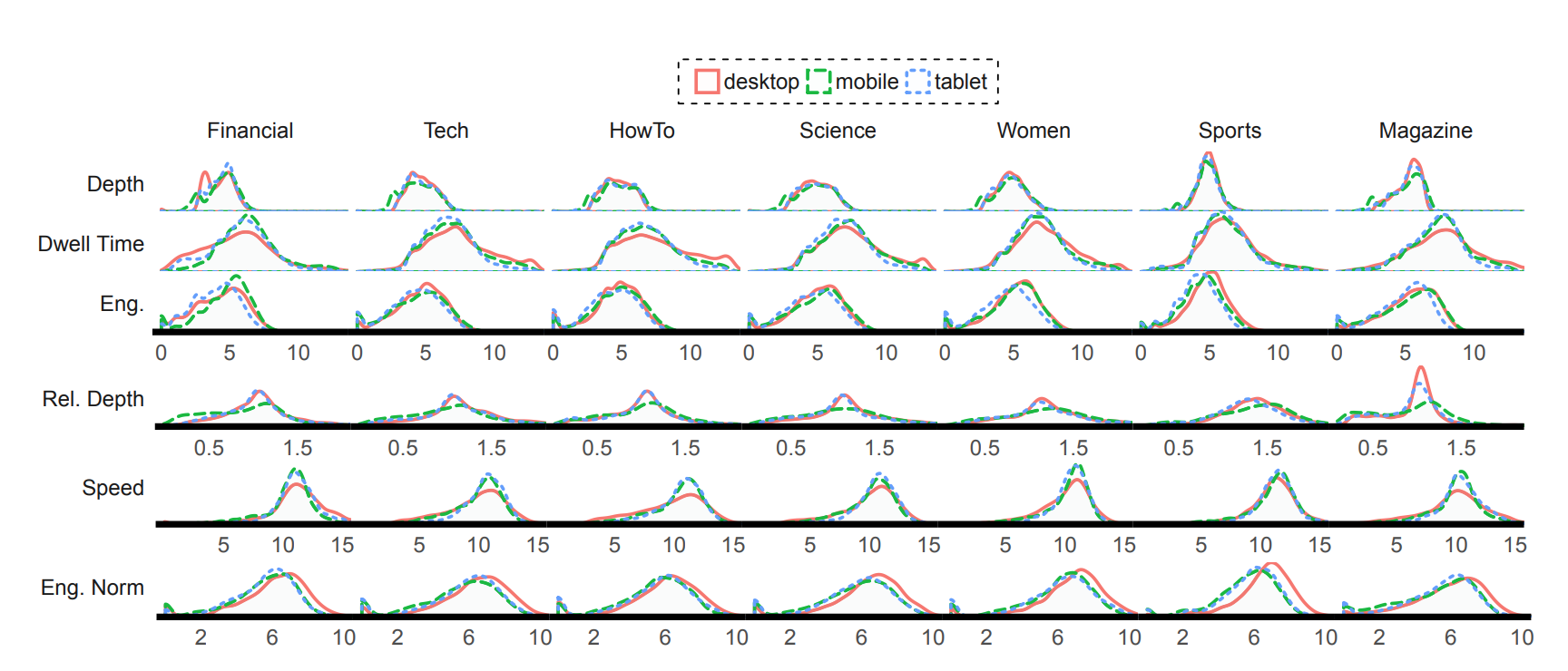

Chartbeat, Grinberg said, already offers publishers pretty good tracking. “It’s one of the few companies that track what happens with a user after they click on a news article,” he told me. “Still, the actual measures it provides are kind of raw. It’ll tell you how much time a person has spent on a page, how far down the page they got, even something called ‘engaged time,’ which is the number of page interactions — mouse clicks, cursor movement, etc. But all of these are not particularly tailored to news; they could work on any web page.” Grinberg tailored these raw measures to create new metrics specifically for news articles.

“Instead of just how far down the page a person got, I’m looking at what percentage of the article they actually covered,” he said. “How far did they go down the page, relative to the length of the article? If someone spent a lot of time on an article and the article is short, that’s a good signal. If they spent the same amount of time on a long article, that’s less good.”

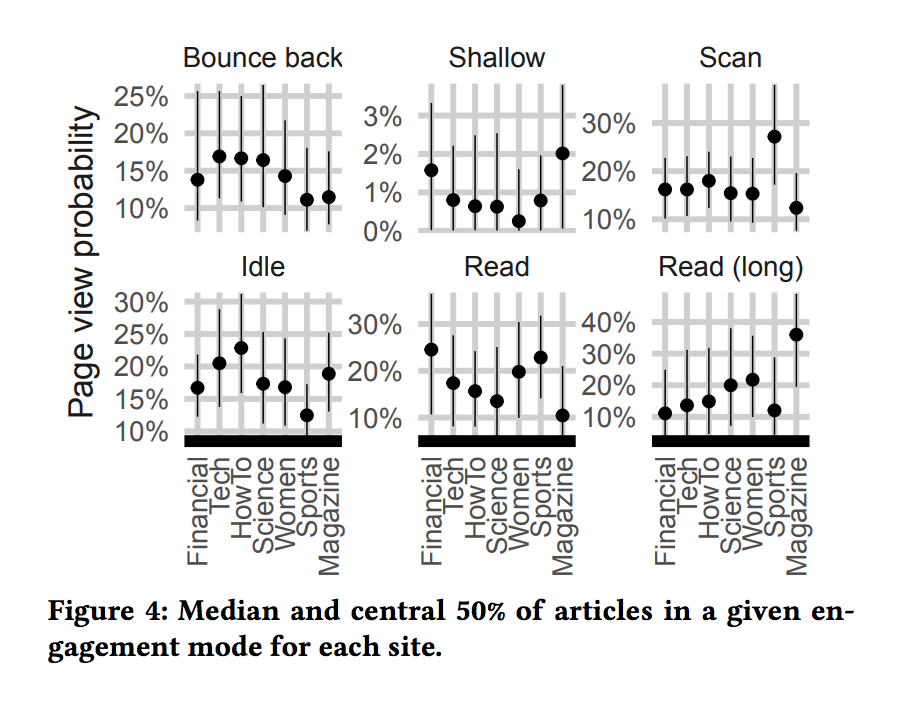

Grinberg was able to identify five types of reading behaviors: “Scan,” “Read,” “Read (long),” “Idle,” and “Shallow” (plus bounce backs, in the case that someone gets to a page and almost immediately leaves). Not surprisingly, different kinds of news sites see different kinds of reading behavior. On the sports site, for instance, “we see there is a lot of scanning. I think what’s going on there is a lot of people go to sports sites in order to find a result, like the outcome of a game, and don’t read the full thing. Another example that stood out is the how-to site, where we see that there’s more idling — people read an article, idle for a little bit, then continue. From looking at the articles themselves, it looks as if people are following instructions on how to do something in the real world.” On the magazine site, meanwhile, people really seemed to be reading for extended periods of time.

In the second part of the paper, Grinberg identifies a measure that he calls “Semantic Information Gain” (SIG) — a way to “[capture] the flow of information within the text of articles, and explains some of the variability in the way people engage with articles.” Grinberg tried to explain this to me:

Imagine that the point an article is trying to make is an actual point in space, let’s say a point on a piece of paper. Similarly, each paragraph could be a point on the same paper. As we consider more and more paragraphs (i.e., p1, p1+p2, p1+p2+p3+…) we get closer to the final point of the entire article with all of its paragraphs.

SIG captures how quickly an article moves toward its final point, passing through all the points along the way made by the individual paragraphs. For example, an article that opens with an abstract paragraph may contain a lot of the information at the beginning and add only a little later in the text. In contrast, a listicle may have a more even distribution of information throughout the text.

SIG can be useful for publishers, Grinberg says, because it ends up being highly predictive of how engaged someone will be with an article, and they should consider it along the other metrics tracked by companies like Chartbeat. “There’s no one-size-fits-all solution,” he said. “The magazine site provided a lot of information up front, and people still engaged in long reading. In contrast, for sports and financial sites, it seems like withholding information at the beginning is associated with longer reads. But publishers could start looking at SIG as they make decisions about strategy and experiment with different story structures to see what works for their audience.”

Grinberg presented the paper, ““Identifying Modes of User Engagement with Online News and Their Relationship to Information Gain in Text,” this week at The Web Conference in Lyon, France.