The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

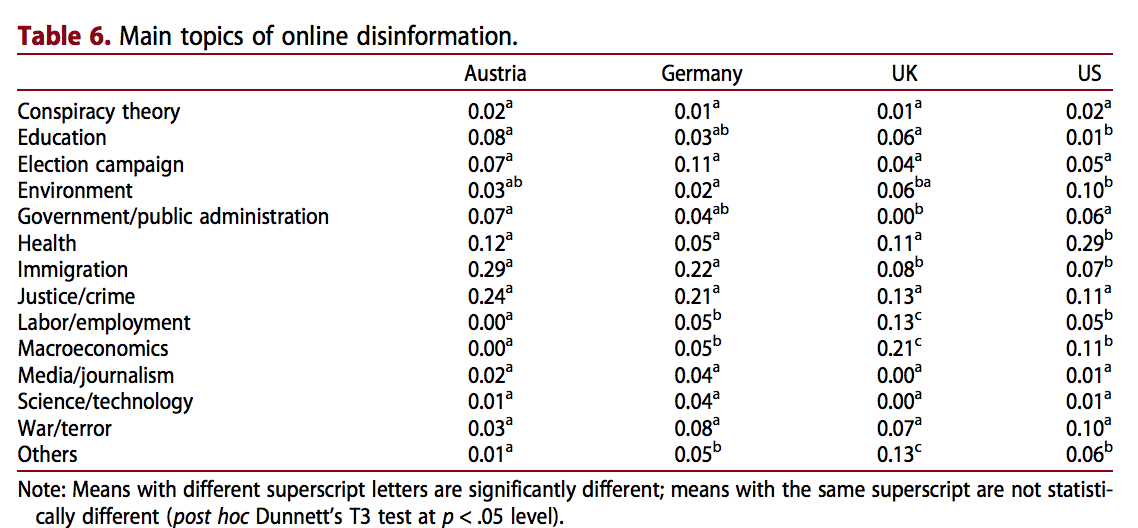

How does fake news differ across Western democracies? Sensationalist? Partisan? Focused on attacking immigrants or politicians? Not surprisingly, fake news is “shaped by national information environments,” writes Edda Humprecht in a new paper, “Where ‘fake news’ flourishes: a comparison across four Western democracies” (Information, Communication & Society). She looks at fake news in the U.S., U.K., Austria, and Germany. Since “political news varies significantly in style, format and quality across Western democracies,” Humprecht hypothesizes that fake news must as well. She wanted to test whether A) “in countries with stronger [public service broadcasting] the share of partisan disinformation re-published by fact checkers is smaller” and B) if “the share of partisan disinformation is larger in countries with lower levels of trust in professional news media and in the government.”

Humprecht looked specifically at activity on fact-checking sites in the four countries, assuming “that fact-checking websites collect all false news stories that have an impact in terms of rapidity and intensity of diffusion within their national environments.” Some of what she found:

In the UK and the US, political actors are more frequently sources of online disinformation and they are more often accused of being responsible for current problems. In contrast, in the German-language countries, online rumors prevail. In these countries, online disinformation often targets immigrants or focuses on the consequences of the refugee crisis. The hypotheses are largely supported: In countries with strong [public service broadcasting] (with the exception of the UK) as well as with high levels of trust in news media and the government, smaller shares of partisan disinformation are found.

Note that more research is needed to determine whether countries with strong public media have less partisan fake news shared: This seemed to be the case in Austria and Germany but there was a lot of partisan fake news in the U.K., even though that country has a strongly developed public broadcasting system.

Second, there’s a “news literacy campaign that provides people with tips to spot false news and more information on the actions that we’re taking. This will appear at the top of News Feed and in print ads, starting in the U.S. and reaching other countries throughout the year.” It appears similar to the fake news election stuff that Facebook has run in some newspapers.

Third, a 12-minute film called “Facing Facts” that is part of a series of posts that Facebook says will somewhat demystify how its algorithm works. You don’t have to watch the video, you can just read this description of it in Wired.

“An explosion” in articles about fake news. BuzzSumo looks at how coverage of fake news exploded after the 2016 U.S. presidential election — but interest in it was actually also growing in the months prior to the election. “It can be argued that if Trump had not been elected in 2016 there would not have been such an explosion in stories about fake news, but there were signs that it was about to become a matter of significant interest.”