The success of media literacy programs is often described in terms of number of people reached, rather than by how (or if) they actually change people’s behavior in the long run. It’s not even clear what metrics to judge them on.

But a new report from a media literacy course run in Ukraine suggests that the program actually was able to change participants’ behavior — even 18 months after they’d completed the course.

The program was called Learn to Discern (L2D); it was run by global development and education nonprofit IREX with funding from the Canadian government and support from local organizations Academy of Ukrainian Press and StopFake (which Nieman Lab covered four years ago).First, the raw numbers: IREX says that its L2D seminars “reached more than 15,000 people of all ages and professional backgrounds” through a “train the trainers” model, in which 361 community leaders were trained on how to teach media literacy skills and then conducted workshops in their own communities — mostly in hubs like libraries. Each leaders trained roughly 40 people.

Here’s what the training focused on:

In contrast to more traditional media literacy courses, the L2D training specifically focused on teaching citizens to identify markers of manipulation and disinformation in the news media. The curriculum intended to foster critical thinking skills, teaching participants not only how to select and process news, but to also discern what not to consume. The training was adapted by citizen trainers to the needs and interests of their workplace or community networks and was reported by participants to last between several hours up to more than eight hours. The majority of participants reported receiving about a half day of training total.

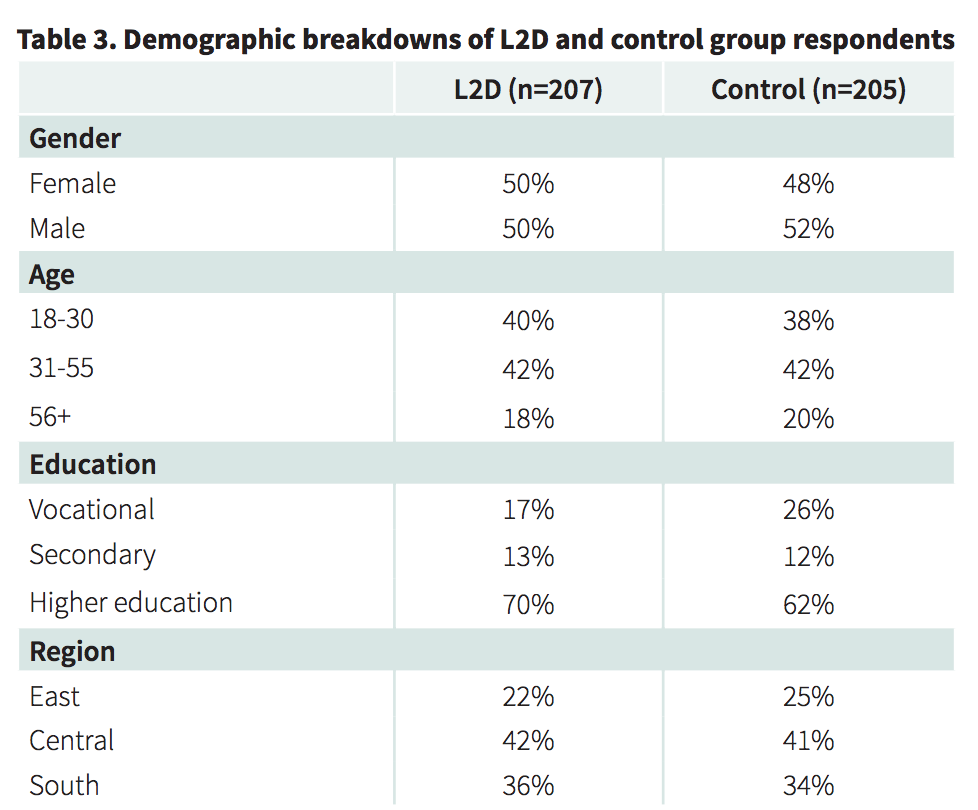

Participants self-reported being positively affected by the program shortly after it was done, but IREX wanted to see if there were any long-term effects. So in 2017, 18 months after the training was complete, it surveyed 412 people, divided between a control group and a group of people who had participated in L2D.

Here’s what participants were surveyed on:

objective news analysis skill; disinformation news analysis skills; news media knowledge, media locus of control; and self-rating of awareness of disinformation, news media analysis skills, news media consumption behavior, trust, and value of objective news. L2D participants were also asked to rate their level of their skills, confidence, and news media consumption behavior before the training, as well as whether they had transferred the information from the L2D training to friends, relatives, or colleagues.

They were asked to assess two stories: An “objective story…about a shooting at the Ukraine–Russia border,” and a “disinformation story…about educational reforms in Ukrainian schools that would remove minority languages in schools (such as Russian).”

Those in the L2D group “had better disinformation news media analysis skills and more knowledge of the news media environment compared to the general population a year and a half after the end of the training.” The effect sizes aren’t huge, but they’re there.

One interesting bit here: Those who had completed the media training were almost no better at assessing the objective story than those who hadn’t done the training. This is a problem we’ve seen before: People aren’t sure that they can trust anything. (Only 25 percent of Ukrainians say they trust the media, according to IREX.) The authors write:

Both groups scored lower for the objective news analysis than the other assessment areas, suggesting that detecting markers of objective news may be more difficult than detecting manipulation and disinformation, and that analysis of objective news was not emphasized as much in the training. The fact that this was the only area for which there was not a statistically significant difference between L2D participants and the control group when education level, geographic region, age, and gender are taken into account, suggests that skill for analyzing objective news needs to be developed on its own and that it likely needs to be coordinated with the skill for analyzing disinformation-based news.

“The biggest challenge in my opinion is to be very careful between raising healthy skepticism but not contributing to overall mistrust,” Tara Susman-Pena, a senior technical adviser at IREX, told Slate. “That is exactly the Kremlin strategy, to get people to think, Oh, there is no such thing as real truth, there aren’t facts.”

L2D Participants certainly also felt that the training had had an effect on them. When they were asked to assess themselves, they “rated their skills in distinguishing true news from false news 30 percent higher than the control group.” (You can decide for yourself whether the fact that their confidence increased more than their actual skills did is a good thing or not.)

The full report is here.

— Can we keep media literacy from becoming a partisan concept like fact-checking? “What is the political identity of media literacy in the U.S. during a hyperpartisan moment?”

— Even smart people are shockingly bad at analyzing sources online. This could be a solution. (See also: “An awful lot of highly educated folks, skilled in all sorts of traditional media literacy, are hopelessly lost on the web.“)