The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

Fact-checking the Mexican election on WhatsApp. Fake news on WhatsApp is a really hard problem to solve. News is spread in closed exchanges and messages are encrypted, making it impossible to know how what’s being spread or how many people are seeing it. False information doesn’t just come as text, but as images and memes. WhatsApp is also by far the most popular social platform in many countries — including Mexico, which holds its general election July 1 (with more than 10,000 candidates running for general and local office).

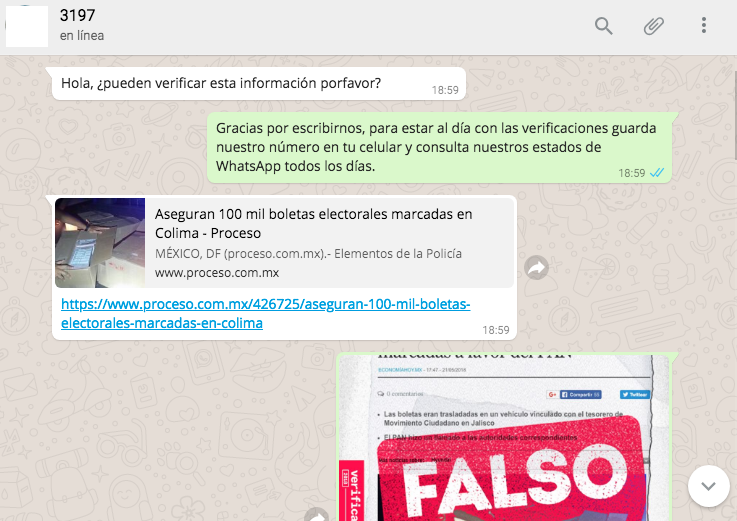

Verificado 2018, a collaborative election reporting and fact-checking initiative led by Animal Político, AJ+ Español, and Pop-Up Newsroom, is trying to intervene in the spread of fake news on WhatsApp — and having some success. Verificado’s mission is broad; it launched in March and has partners in 28 of Mexico’s 32 states. It’s fact-checking and producing content across multiple social platforms, not just WhatsApp — but I was particularly intrigued by what it’s doing there.

“We don’t want to invade. We understand that WhatsApp is not like Twitter or Facebook — we see it as a private space for the users to interact with family and friends,” said Diana Larrea Maccise, content editor at Al Jazeera Media Institute. “So instead of using broadcast to spread our debunks, we opted for an individual relationship.” Verificado set up a WhatsApp line where users can send it information to verify; it then responds to those individual users. “We are not going to use our broadcast list to spread the debunk to people who aren’t actually inquiring about it,” she explained.

To get the fact checks to more people, though, Verificado features them in its WhatsApp statuses — “a daily average of 10 different statuses in our WhatsApp, so the people who are subscribed to our WhatsApp line will see these debunks that are constantly being updated,” Maccise said. The users can then directly share those statuses to their own networks. Each debunk — Verificado is referring to them as “vertificados,” a combination of “vertical” and “verify” — consists of the viral image, with bullet points about why it’s true or false stamped over it.

While the process seems fairly individualized, it is scaling. Verificado’s WhatsApp line officially launched on May 18; two weeks in, 4,800 people have subscribed to it and it has received a whopping 18,500 messages — 13,800 of which it has answered. (Maccise cautioned that “messages” here refers simply to interactions — requests to verify content, as well as any other message, such as a greeting. But Verificado plans to filter out actual fact-check requests more specifically in a report it will release after the election.) Each of its published debunk statuses has gotten about 1,000 views (though in reality it’s probably more, since users who disable the read receipt feature aren’t counted in WhatsApp’s analytics). And all of this is handled by just 4 people on Verificado’s end.

What kinds of information is coming in to be verified? Maccise said it’s mostly images, and mentioned that it’s usually impossible to know where each piece of misinformation originates — “we don’t know if it started through a WhatsApp account with someone who made a meme, circulated it within WhatsApp and then it jumped to Facebook or Twitter, or if it was the other way around…That’s a huge challenge, not only for us, but for all journalists trying to make sense of how misinformation spreads.”

You can add Verificado on WhatsApp: 55-1245-5032, or follow it on Facebook and Twitter.

“It’s all of you, dear readers, plus your chacha, mama, second, third, fourth cousins and even that uncle you don’t like very much.” India’s The Quint posted on the spread of fake news in family WhatsApp groups. “Try telling your mom that the news she just shared with you is fake. She will respond by saying that the only real news in the khandaan is that her aulad is such a nalayak! On second thoughts, the unending, overtly cheesy Good Morning messages of relatives seem better than all this fake propaganda, to be honest. So rishtedaars, keep them coming, even though these messages have apparently given Silicon Valley many sleepless nights!”

At least 21 imprisoned on fake news charges. This ABC News report offers a good overview of how countries are clamping down on journalists using “fake news” rhetoric. At least 21 journalists worldwide were imprisoned on charges of fake news in 2017, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.