Editor’s note: Mark Frankel, a social media editor at BBC News, recently finished a Knight Visiting Nieman Fellowship here at Harvard to study how journalists can best uncover and report on stories sourced from audiences on “dark social” apps, message boards, and other private, invitation-only platforms. What follows is an abridged version of a full report on his findings.

In early 2013, residents of East Boston were faced with a proposal for the construction of a billion-dollar casino complex in their neighborhood. A community collective action group called “No Eastie Casino Coalition” formed in opposition to the construction of the complex, involving a range of people from the community, including many young people who organized via social media platforms.

This campaign, documented by Lynn Schofield Clark and Regina Marchi in their excellent book Young People and the Future of News, was largely overlooked by the mainstream media at the time. The Boston Globe described the gambling resort proposal as “widely considered a lock” and was surprised to see it rejected when it came up to a public vote, 56 to 44 percent.

The campaign to block the casino revealed an interesting dynamic. Clark and Marchi found that students participating in the effort chose to organize within closed circles on Snapchat, rather than in more open forums like Facebook or Twitter. When the authors looked at their use of social media in greater detail, they observed that the students chose a variety of platforms for different forms of activity: “Facebook for organizing and talking about protests, Twitter for messages to followers about activities, and Snapchat for real-time unfolding of events.”

Media organizations have often struggled to adapt their newsgathering and reporting to the reality of disparate news consumption habits and a public that increasingly favors peer-to-peer messaging platforms and social media networks over more public forums.There are challenges for all journalists in discovering and verifying stories we don’t “own” or can’t attribute to other known opinion-formers. There are ethical dilemmas, too, in journalists seeking to insert themselves into unfamiliar online communities, either openly or undercover.

But is there more we can — and should — be doing as journalists to move our reporting closer to the communities we seek to serve? Is there still value in news journalists dwelling in social media platforms where participants are routinely attacked before they’re heard and where media manipulation is so dominant? And if so, can and should journalists look a little deeper into this local beat and seek greater insight from digital communities in private, invitation-only networks?

For a period of five weeks as a Knight Visiting Nieman Fellow, I set myself the task of answering three straightforward questions from the perspective of a reporter.

This project is not about those who seek shelter in invitation-only online communities in order to sow hatred, plant conspiracies, or participate in illegal activity (many others, like Jamie Bartlett, have written extensively on that subject). Instead, my focus is more on those who use the anonymity and moderation of these online communities to find and make new connections with others, to share often personal stories born out of genuine insight and experience, in places where journalists seldom explore.

If people seek the privacy of a forum with like-minded individuals to share their views, they’re unlikely to think well of a lurking journalist. As I will discuss in the course of this report, alongside the discovery and verification of stories of interest in these communities, building trust over time is vital. Many of those who inhabit these networks are looking for stories to find them in their news feeds and to connect them with their lives. It’s undeniable that the public we serve is spending more of its time in chat apps, social media groups, and other peer-to-peer environments. We’d be foolish to ignore the opportunity to engage with them where they feel most at ease.

I could have chosen to look at any number of messaging and social media platforms, from WeChat to Viber, Telegram to Signal, or even Slack. For the purposes of this project, I narrowed my inquiries to social media networks where news was already a lively preoccupation : one “closed” (closed Facebook groups), the other largely “open” but underused by many journalists (subreddit communities). I also investigated the challenges of using WhatsApp groups in reporting. And I examined how hyperlocal forums, like Nextdoor, and the online gaming community on Discord offer journalists new entry points to potential stories.

Closed online communities are often very open to those willing to participate in a constructive way. The barriers to entry are often low and may simply reflect how much you are willing to reveal of yourself and abide by the rules set by the moderators. Users can search for groups that are either public, closed, or both using keywords in Facebook’s graph search (or even via Google), and are offered local personalized recommendations too, based on their activities and friendships.

Facebook is testing a new feature to allow people who don’t wish to be identified by their real persona to have secret profiles in a group, provided group admins accept them, according to Anna Bofa, the head of community partnerships for Facebook in EMEA, who works closely with the product team on Facebook groups. Creating a safer environment for people to feel more willing to share is one matter, but secret profiles will undoubtedly lead to further challenges, as people misuse them to scam and disrupt conversations or to lurk in groups for ulterior motives.

At present, Facebook group administrators require users to abide by the rules of a group, acknowledge their interest in the subject or answer some basic identity questions before being invited into the discussion. In most cases, the people managing groups are just looking to avoid conversations being disrupted, members being harassed, and moderation becoming overly burdensome. I encountered few instances where those introducing themselves as journalists were not welcome to participate.

A simple search for groups with a focus on Brexit in Crowdtangle is a good case in point. Of the 165 groups I could discover (searching June 5) via a “Brexit” keyword search (for title/description), only 59 of them were public. The majority of the groups with more than 1,000 members were closed. In other words, there is no way for journalists to observe conversations in many of these groups without seeking to join them first.

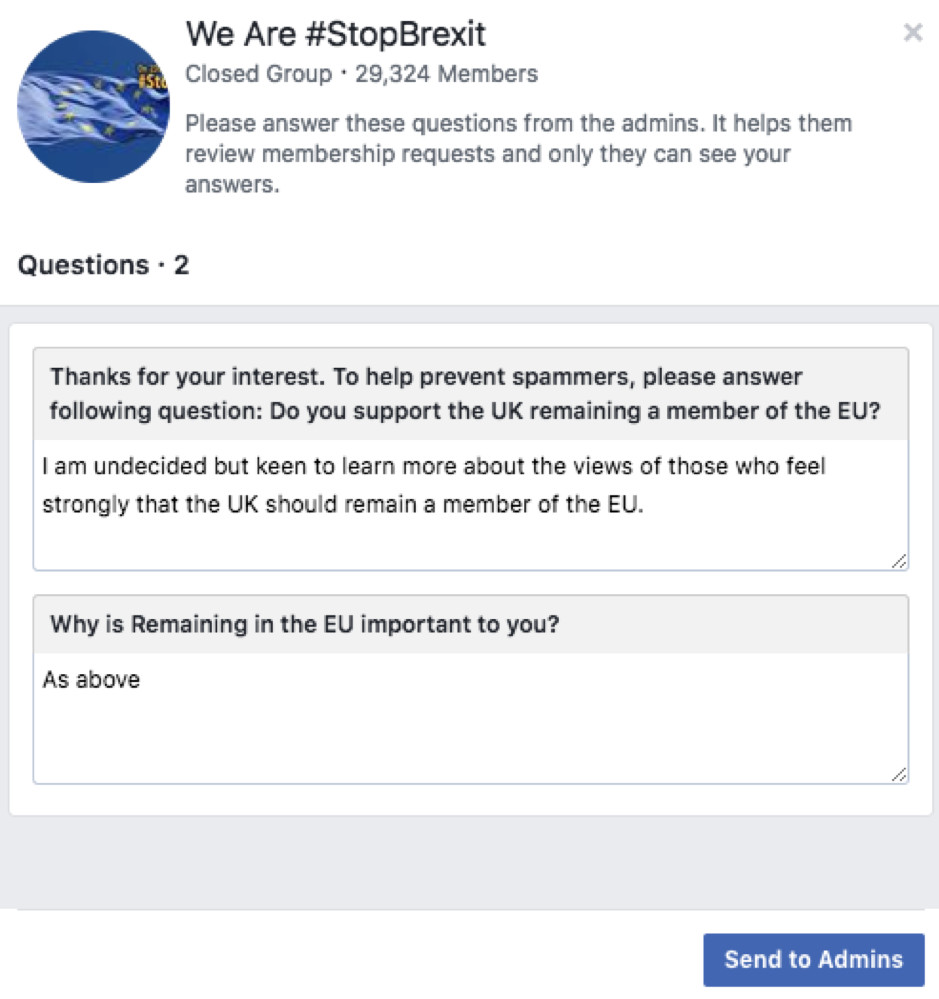

The second-largest group associated with Brexit (in terms of membership) was a UKIP-supporting, closed group. Those seeking to join were asked to answer the questions in the screenshot below. I answered and gained entry shortly after:

The same issue presented itself for those wishing to join a large anti-Brexit closed Facebook group. Again, there are ways of approaching these questions as a journalist without perjury, or compromising your impartiality and objectivity.

How can journalists create Facebook groups and play a more active role in the moderation of different communities on given subjects? What I have outlined so far requires journalists to do little more than “lurk” and observe the chat. But many journalists and news media have created Facebook groups themselves to encourage users to share stories they wouldn’t otherwise hear, and to build new audiences for their journalism. (In its broader rhetorical shift to attracting more “meaningful interactions” on the platform, Facebook itself offers advice on group creation and management, and has highlighted a number of news organizations for their work in creating groups over recent months.)

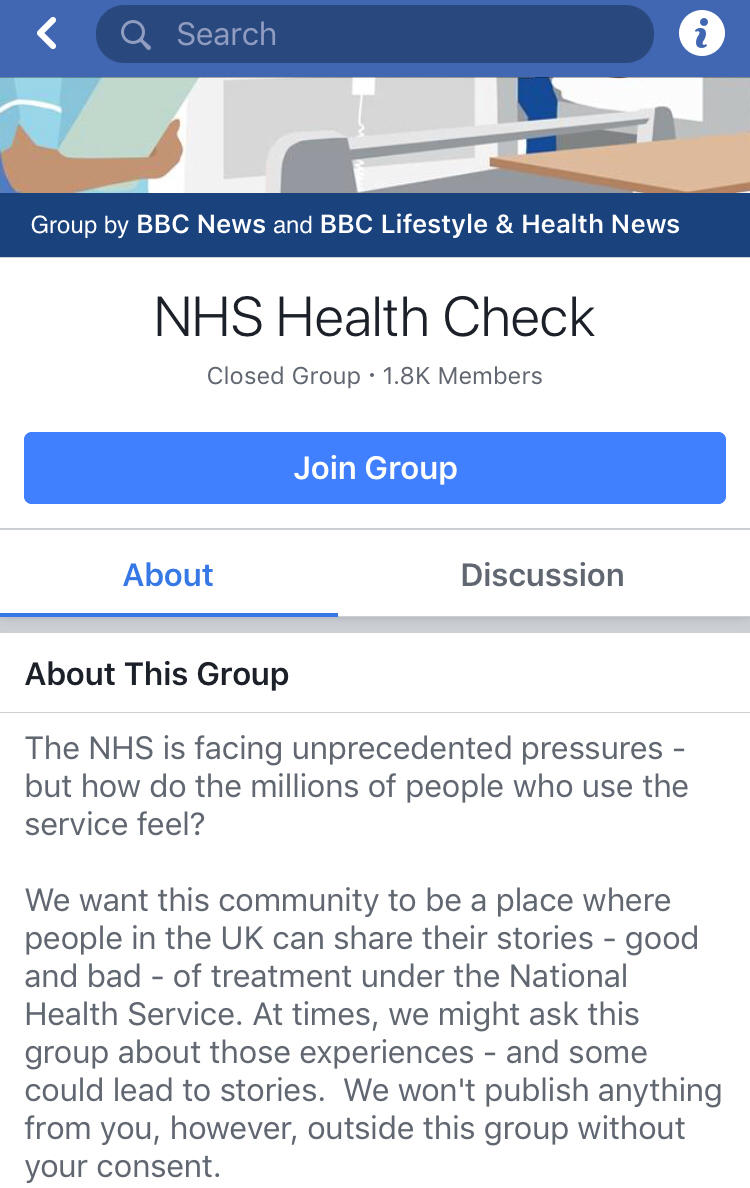

News outlets have thought hard about how best to focus on Facebook groups — the specificity of the topic, whether to make the groups public or closed, and of the resource commitment in ongoing moderation. Colleagues of mine at BBC News, for example, have created closed Facebook groups around hyperlocal niche topics (such as on a campaign against tree-felling in Sheffield) and around much broader interest (for example, for people who use the U.K.’s National Health Service).

News outlets have thought hard about how best to focus on Facebook groups — the specificity of the topic, whether to make the groups public or closed, and of the resource commitment in ongoing moderation. Colleagues of mine at BBC News, for example, have created closed Facebook groups around hyperlocal niche topics (such as on a campaign against tree-felling in Sheffield) and around much broader interest (for example, for people who use the U.K.’s National Health Service).

The specificity and narrowness of a topic has proved an easier sell to audiences with direct interest and experience and, in the case of the group on Sheffield tree-felling, led to a video story which proved highly engaging. There were challenges for the group admins in ensuring the members of this group didn’t use the forum to campaign for particular candidates during local elections and it was also hard to move participants on to other “local democracy” issues — despite attempts to rebrand the group — once the group admins felt the topic had run its course.

The broader-themed NHS Facebook group is a different challenge altogether. The group may be clear in its remit, but members appear to have joined for a variety of reasons. Some are keen to share anecdotes and respond to posts from group admins and members with their own experience and insight. Others, on the other hand, are looking for advice or want to campaign on a specific issue. Moderation is a big, ongoing effort.

Bofa from Facebook told me that the company is looking at more auto-flagging options for troublesome words and phrases mentioned in groups and the ability for moderators to see posts before they’re made public. Still at issue currently is the 24/7 commitment of moderators to the group: A group may have clear rules, invitation questions for those looking to join, and controlled membership, but there’s no way to ensure complete safety for those seeking to share in a Facebook group.

Though requiring significant investment from moderators, closed groups created by journalists can be hugely rewarding. The BBC News family and education social media team created a Teen Mums closed group to attempt to reach an audience we struggled to engage. The group needed to be grown and nurtured over several months, and it was clearly inappropriate for some of us on the team to be group admins. Over time, a number of women in the group have shared very personal stories that we would have been unlikely to have heard via more traditional newsgathering. This is Your Texas, VoxCare, and BBC Money’s Affordable Living are other good examples of well-moderated, closed groups where conversation often leads to story ideas for the publication that runs the group.

While the sense of exclusivity and privacy of a closed group do sometimes lead to more meaningful conversations, “people can’t share material from a closed group outside of that walled garden,” head of audience engagement at Trinity Mirror regionals Karyn Fleeting pointed out to me. Fleeting oversees regional digital teams throughout England that collectively manage dozens of Facebook groups. With the exception of groups they’ve created around ongoing court trials, page admins have preferred to focus on public Facebook groups, and have had particular success with groups dedicated to breaking news, traffic and travel alerts, and “good” news.

California-based company Spaceship Media has had a good deal of success with several closed Facebook groups and serves as a useful case study. The company’s founders Eve Pearlman and Jeremy Hay support a model of “dialogue journalism” that is a partnership between interested media and the communities they serve. They seek to create a trustworthy, convivial and carefully moderated space for people to share their thoughts and experiences on a given subject. When appropriate and relevant, journalists are invited in to build relationships, seek quotes, and amplify selected stories from the group to a wider public.Spaceship Media runs a variety of initiatives, including conversations about politics with a select group of Alabama women who voted for Trump and California women who voted for Hillary Clinton; a collaborative discussion about guns (supported by by AL.com); and an ongoing project focused on women called The Many, which has brought together several hundred women from across the country into a moderated Facebook group to discuss political, social and cultural issues in the run-up to November’s U.S. midterm elections.

I was fortunate enough to be invited in to observe the month-long Facebook discussion on guns in April and May of this year. I witnessed a fascinating ongoing conversation between 135 courteous and well-intentioned participants from a variety of backgrounds and points of view. Many of those in the group were moved by the views and perspectives of others and a number of them were keen to keep the conversation going in different ways at the end of the month. As Hay pointed out to me, more than half of the group participants were just listening rather than posting, but everyone had a story and interesting perspective to share. Here are two excerpts, shared publicly with the permission of the two people who published their thoughts to the group in the first place:

John Counts is a reporter for MLive, specializing in police and court stories, based in Michigan. He was both a moderator and reporter in the guns group and has written about the “dizzying amount of words” he and other moderators needed to keep up with. They had to introduce guidelines for members on “stats-dumping,” encourage women to speak up to counter mansplaining, and there was more than the occasional angry exchange to mediate. Moderators could tell which posts submitted to them were likely to generate more heat, Counts said.

Counts, who took on an evening moderation shift to work around his reporting commitments, told me that there were times when the conversation “got a little crazy.” He recounted one particular episode to me when a staunch second amendment rights supporter, who was in an African-American gun club, clashed with a white police officer from Massachusetts over racial profiling, and he had to weigh in to keep the peace. The following post of his received dozens of constructive responses:

Around a dozen journalists were invited into this particular group. Unlike many of the other projects, where Spaceship Media acts as more of an intermediary between the journalists and group participants, this group operated under the expectation that journalists would approach members directly if they had story ideas or wished to pick up on comments, and as a result many news stories flowed from this initiative.

Another Spaceship Media group, The Many, is evenly divided between those identifying as Democratic, Republican, or another affiliation. I was allowed to observe The Many for a week in late June to observe the conversation. Some of the discussion was overtly political and topical. I witnessed a fascinating conversation, for example, between a number of women about the implications of the Justice Kennedy Supreme Court retirement on Roe v. Wade. In another thread, women discussed media coverage of the shooting in the Capital Gazette newsroom in Maryland. Conversations were wide-ranging, however, and included a focus on race, motherhood and childhood summer memories.

This community is already three times larger than the guns group, and requires three moderators, two of whom are full-time. They work eight hour shifts with a one hour overlap. When I spoke to her, Adriana Garcia, a seasoned journalist and currently project manager for The Many, had been awake until 2 a.m. monitoring the conversations in the group. There’s ongoing discussion about “slowing things down,” and what the optimum size for a group like this should be before it becomes too hard to moderate. As Spaceship Media’s Pearlman told me, “we’ve been bugging Facebook about a 9-to-9 limitation for some time now,” as it’s important to be able to switch off.

Garcia said she was fascinated to see how much is posted during the workday, though the group typically does see bursts of activity Sunday and Monday nights. She’s also witnessed some fights, and has had to mute and block a few participants, but the vast majority of participants in The Many have been highly engaged. Some women have forged new friendships from the group, and the open rate for her weekly group newsletter is “very high,” Garcia told me.

The creation and moderation of a closed Facebook group of this kind is no simple feat. Following an initial call-out via media partners, every participant is carefully selected to ensure the group is balanced and equally weighted (on gender, ethnicity, age, location, and points of view). Spaceship Media also conducts its own questionnaires to determine what exactly participants are keen to know about one another. The commitment that the group members make to the project is matched by the efforts of three moderators who, as I observed, were posting on a regular basis to encourage conversation, manage expectations, and help foster a sense of trust between participants and journalists.

It’s clear that many news organizations lack the capacity to run initiatives at this level on their own. But as Hay and Pearlman were quick to tell me, everything they offer is freely available.

“If a news organization wants to invest in a local beat, this is one way of doing it. You put resources into your reporter and give them 10 hours a week to invest in group moderation,” Hay said. “The only question is whether news organizations are serious enough about the endeavor in the first place.”

Proceed with caution: False information in WhatsApp groups is ubiquitous and has horrific real-life consequences. Activists and journalists have taken to creating online fact-checking services in an attempt to stem the flow of misinformation on the chat platform; these include La Silla Vacía in Colombia, the recently wrapped-up Verificado in Mexico, and many other coalitions of academics, journalists, and activists in Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Asia.

Beyond the problem of false information, it’s hard to find WhatsApp groups with noteworthy conversation without a tip and an invitation to begin with. A simple Twitter or Reddit search for groups will turn up some random results. But many groups that are advertised publicly are often of limited interest and/or full (since groups reach capacity at 256 members). One opportunity for journalists on WhatsApp is when users seek to advertise a group invite to those in another closed network, such as a Facebook group. I discovered a handful of interesting groups this way. There’s no introductory vetting process for WhatsApp groups; if you have an invitation link and the group isn’t full you’re in — until and unless a group admin chooses to boot you. This, of course, presents an immediate ethical challenge if the journalist is undercover. Will you reveal yourself as a journalist when you enter the group, or simply lurk and observe? To act incognito will require some editorial justification and a degree of explanation to those group members if and when you choose to make direct contact with any of them.

Beyond trawling through Twitter, Reddit, and Google, or being fortunate enough to find a potentially worthwhile invitation through a closed Facebook group or on a Discord server, or being invited into a group by a friend, colleague, or local club or society, another possible avenue for journalists into important WhatsApp groups is through an NGO. Witness is one such organization that’s worked closely with communities to document human rights abuses through eyewitness video.

“The biggest impediment in this space is trust,” Priscila Neri, a Brazilian journalist and activist who oversees Witness’ work in Latin America, told me.

A large percentage of the footage collected in Brazil today is recorded and disseminated via social media apps and platforms — particularly WhatsApp. Both the paramilitary and police use WhatsApp groups to coordinate their own activity. Local community groups use WhatsApp routinely to alert, update, and share information. The Coletivo Papo Reto is one such group of community-based activists who use mobile phones and social media to document what they encounter in the Complexo do Alemão, a group of 16 favelas in the northern part of Rio de Janeiro. Today, representatives from the favelas participate regularly in carefully controlled WhatsApp groups to verify and share information on local incidents. These are then brought to greater public attention through a public Facebook page and to trusted journalists via Witness for further amplification. The verification process and admissibility of these videos in any legal process remains contentious with authorities in Brazil, but Witness works hard to ensure the videos and the chat history are properly recorded and archived. Journalists may not be able to inhabit the WhatsApp groups themselves, but they can, in partnership with Witness, see and assess valuable first-hand evidence.

This “chain of communication created at a local level can make a big difference, particularly if what’s filmed on WhatsApp is admissible in court,” Neri told me.

How does an independent journalist navigate WhatsApp for newsgathering in India, the messaging platform’s biggest market? WhatsApp has seen phenomenal user growth in India and, as New Delhi-based journalist and political commentator Shivam Vij noted, is as widely used by politicians and activists as it is by members of the public.

“Most Indians are discussing politics via the medium of WhatsApp today,” Vij told me. It’s vital, then, that journalists have a ring-side seat. Vij has been invited into a number of Hindi-language WhatsApp groups through friends and other contacts. One day, someone he knew sent him a single invite link to a WhatsApp group and from there, he was invited to many more. Subjects of those groups range from local politics and elections to food pricing, inflation, cow protection, the role of the army and Islamic militants. Many other groups simply share memes, jokes, and banter at a hyperlocal level. In many of these closed forums, Vij observed highly partisan Hindu nationalism — the perspective of India’s ruling BJP party is particularly dominant (“The BJP are ahead of other parties in matters of technology,” he told me, and “many software engineers support the party.” This screenshot of a collection of Hindu nationalist-supporting WhatsApp groups all switched to the same profile picture on the same day, Vij said, a sign of some central organization.)

“Most Indians are discussing politics via the medium of WhatsApp today,” Vij told me. It’s vital, then, that journalists have a ring-side seat. Vij has been invited into a number of Hindi-language WhatsApp groups through friends and other contacts. One day, someone he knew sent him a single invite link to a WhatsApp group and from there, he was invited to many more. Subjects of those groups range from local politics and elections to food pricing, inflation, cow protection, the role of the army and Islamic militants. Many other groups simply share memes, jokes, and banter at a hyperlocal level. In many of these closed forums, Vij observed highly partisan Hindu nationalism — the perspective of India’s ruling BJP party is particularly dominant (“The BJP are ahead of other parties in matters of technology,” he told me, and “many software engineers support the party.” This screenshot of a collection of Hindu nationalist-supporting WhatsApp groups all switched to the same profile picture on the same day, Vij said, a sign of some central organization.)

During February 2017 state elections in India’s most populous state Uttar Pradesh, Vij saw how political narratives of different kinds played out across Hindu-nationalist WhatsApp groups. BJP activists promote a different agenda at national, state, and local levels, according to Vij, a strategy evident in these group discussions. He recounted a story of an encounter he had with a teenager in a village in Uttar Pradesh, where the boy told him that he used WhatsApp regularly and then showed him an extensive gallery on his Android phone of mostly political images. A meme had been circulating of a woman on a Indian bank note with the phrase “Sonam Gupta is unfaithful.” The boy had an obscene photoshopped version of the same image with a picture of Prime Minister Modi grabbing the woman by her breasts and a message: “Modi has found Sonam Gupta.” This image was being widely distributed through WhatsApp groups at a local level to bolster Modi’s machismo persona — all of India had been searching for the unfaithful woman, but only Modi could have found her.

Vij is mindful of the significant editorial and ethical challenges in journalists writing about what they observe in WhatsApp groups. Much of the extreme right-wing material he sees is unpublishable, and he said he’s conscious of not incidentally performing the function of a surrogate to party political propaganda or assisting in any way in the dissemination of fake narratives. Incorrect information is a significant hazard, but so is party apparatchiks using WhatsApp groups to divert the attention of local supporters and party members away from unfavorable news.

It’s clear that these groups provide journalists with a valuable bird’s-eye view on a community they may otherwise struggle to hear. Alongside the spin and propaganda of certain messages and memes, there are also frank exchanges between party members, activists and local communities and, as Vij has demonstrated, there are ways to write productively about those exchanges. It’s impossible to know whether a meme in any given WhatsApp group originated from a party official or a member of the public. Many of the messages are repeated and shared across groups and few participants are open about their affiliations in their profiles. There are undoubtedly secret groups where invitation links are more protected and conversations less open, but there’s plenty to keep any journalist occupied in other groups if you have the time and energy to sift through the messages. During the May state elections in Karnataka, the BJP was running around 25,000 WhatsApp groups (to the Congress Party’s 10,000), according to Vij. A way into WhatsApp group chats will be critical during the 2019 Indian general election.

How do you figure out where to even start looking for stories on Reddit? Reddit has millions of monthly active users, with more than half of them based in the U.S. It’s a predominantly open platform, with only a small number of private communities. For the uninitiated, the tens of thousands of active subreddit communities can be a daunting region of the web (for the essentials on what Reddit is and how to use it, see this wiki guide; I also list a few of my preferred subreddit communities at the end of this section). The company recently announced a news tab “for those seeking a home for content that the community surfaces from a group of subreddits that frequently share and engage with the news.” Time will tell if the news tab really provides an easy way into some larger news communities for redditors. However, many of the most interesting stories circulate in a large variety of comment threads, and not always in the most obvious subreddit communities.

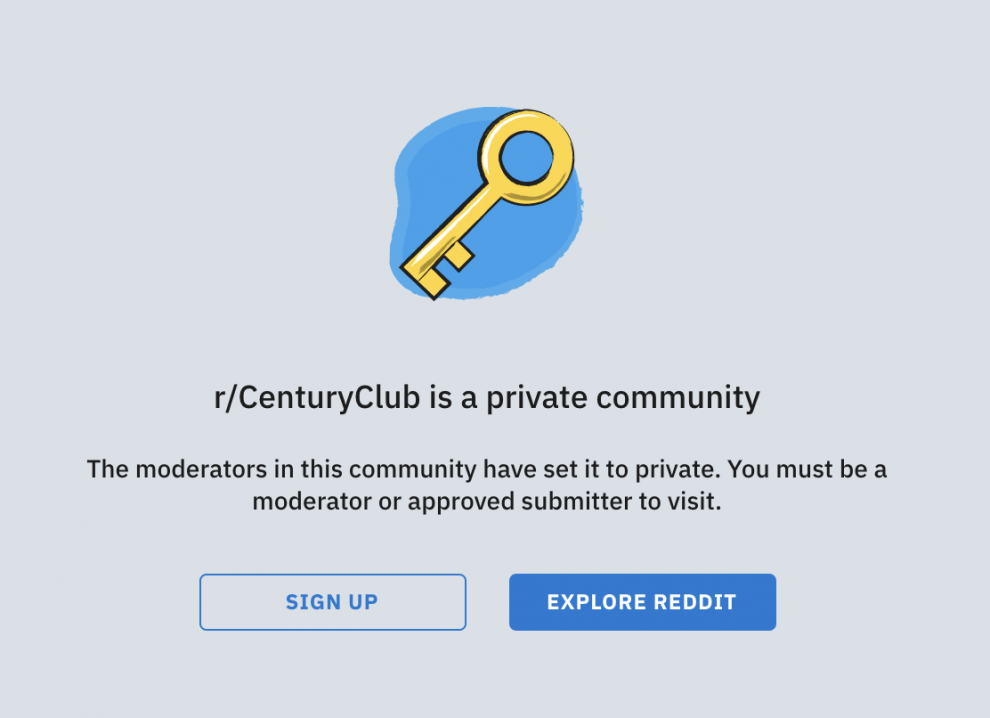

Reddit is also home to a few invite-only communities. Private subreddit communities tend to be very small (less than 20 subscribers), and many only exist to help moderators with logistics. There are a few much larger private subreddit communities: For those who boast over 100,000 karma, for example, there’s The Century Club.

Reddit is also home to a few invite-only communities. Private subreddit communities tend to be very small (less than 20 subscribers), and many only exist to help moderators with logistics. There are a few much larger private subreddit communities: For those who boast over 100,000 karma, for example, there’s The Century Club.

It’s also possible to discover other “private members clubs” of potential interest where, as with WhatsApp and closed Facebook groups, journalists would undoubtedly need to make an editorial rationale for going under cover before contacting community moderators. (Here are a few I found simply by searching for “Brexit” and “Trump” on Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/The_British/; https://www.reddit.com/r/Mr_Trump/; https://www.reddit.com/r/polandballtalk/; https://www.reddit.com/r/EnoughHillHate/.)

Some reporters have already embraced Reddit for stories: The New York Times’ Kevin Roose’s exposé on deepfakes is a good example. Others have embraced AMAs. A few news organizations, like The Washington Post and BBC News, have created profiles there to build new connections with audiences and help encourage sharing or upvoting of articles (and, consequently, not insignificant referral traffic back to their own news sites). But can journalists gain by adopting a greater focus on public subreddit communities in particular? Should we be looking to create “reddit reporters” in our newsrooms? To help me answer these questions, I met with Benjamin Brock Johnson, the host of a weekly podcast from WBUR called Endless Thread, which launched this past January and finds its stories from subreddit communities. (The show is sponsored by Reddit, but maintains its editorial independence, according to Brock Johnson.)Here’s one way reporters responsibly turn subreddit conversations into stories. Brock Johnson and two colleagues spend hours each week combing through conversation threads in subreddit communities looking for under-reported stories. As the show has become better known, more redditors have reached out to them directly. But for the most part, they send a lot of messages themselves and have come across numerous “throwaway accounts” (where an account has “throwaway” in the username, so you’re unlikely to hear back).

“Lots of stuff on Reddit is quite insider, geeky, and offensive, but there are some genuinely fascinating stories too if you root through the comments on specific posts,” Brock Johnson said. “Who would have thought that there would be such a vibrant community for the homeless on Reddit, for example?”

Endless Thread looks for people for its shows who can speak from firsthand experience. Verification is a challenge with a small team but, to Brock Johnson’s knowledge, they haven’t been duped yet. When they reach out to potential contributors, they take care to protect that person’s anonymity where necessary. Endless Thread will always send a private message if they’re keen to talk directly to someone, give due credit and link back to articles as and where relevant.

Redditors don’t respond well to interlopers. The credibility the journalists themselves have on Reddit is important. For those seeking to develop a local beat on the platform, establishing a foothold there yourself is critical — demonstrate a clear appreciation of the grammar and lexicon used by Redditors (see: the credits and shoutouts to Redditors at the end of Endless Thread episodes) and a proven background of activity in different subreddit communities. One of the first things a Redditor will do when you send them a message is look at your profile before they reply.

Reporting on Reddit requires important ethical considerations (and many of the episodes the Endless Thread team have done cover delicate, extremely personal issues such as addiction, death and suicide, sexuality, and homelessness). One Endless Thread podcast focused on how a recovering heroin addict had found solace in a Reddit opioids community. The team had to discuss their responsibility to him in broadcasting his story — and think through it again when the interviewee wanted to set up a way for other recovering addicts to contact him for help through the show.

Brock Johnson agreed that Reddit is a rich local beat for journalists seeking to uncover original stories from a range of communities, but was wary of the practice of over-relying on it for local reporting.

“It’s a massive treasure trove of people talking about real issues and news organizations would be wise to be more active in the community. Not parachuting in to report on individual stories, but actually participating in the conversations there,” he said. But the subcommunities on the platform are randomly organized and policed by moderators, “all of whom have their own outlooks and whims,” meaning each community is only as strong and as open as the moderators allow it to be.

At face value, Discord, founded in 2015, is an “all-in-one voice and text chat for gamers that’s free, secure, and works on both your desktop and phone.” For journalists, the platform can, if used discreetly, connect them to hard-to-reach communities.

Over 40 percent of the more than 130 million registered users active on Discord (up threefold in a year) are based in the U.S., but millions of them are located around the world too, including in Canada, Brazil, the U.K. and France. Although the Fortnight server is currently the most popular (in terms of registered members), there are hundreds of other active and publicly searchable communities within Discord, where discussion ranges well beyond gaming into many other potentially newsworthy topics, from politics and current affairs, to sexuality and mental health, to gun use and ownership, to hate speech, and even to Brexit. (Many Redditors are also active on Discord.)

The platform has attracted a good deal of attention for its propensity to become a breeding ground for hate speech and media manipulation. The anonymity and privacy that users can take advantage of through the platform has been used by individuals and groups with extremist agendas, many of whom also have profiles on 4chan and 8chan (a simple internet search for discord.gg servers via 4chan is a sure way into a world of far-right conspiracy and hate). Some Discord users are conscious of “purveyors,” and those with an extremist agenda have deliberately sought to plant stories for journalists to find, only to revel in the publicity that followed publication of a story. The leaking of confidential files on Emmanuel Macron hours before voters went to the polls in the French presidential election is a good illustration of this tactic.

The primary purpose of Discord has always been for users “to chat about gaming, anime, and pornography,” not about mainstream political discussion or direct action, said Brian Friedberg, a research analyst at Data & Society who has spent time studying the ebb and flow of chat on Discord servers. The platform is also a great repository of information (witness TheRedPill, for example, which is as active on Discord as it is on Reddit, and regularly shares reading lists). Despite its fundamental use cases, in recent times Discord has become a natural home for the far-right, particularly over the Unite the Right rally in August 2017, as the group Unicorn Riot has documented so effectively. To Friedberg, these Discord users “are essentially constructing fanfictions on a right-wing revolution.”For those less comfortable about talking in a fully open or public online forum, Discord provides an alternative outlet. Through my daily searches in different servers, I found that many individuals would share links to documents I hadn’t seen on public websites and spoke freely about a number of subjects, from the Trump administration’s attitude to child migrants to Supreme Court judgments and local gubernatorial races. In many ways, the platform hearkens back to those early days of the social web where largely anonymous groups hung out on MySpace, AOL, or Yahoo. Discord “gives you an immediacy of watching an active conversation,” Friedberg said, “and the chance to see the way that ideas are debated and thrown back and forth and how meaning is made in very self-selected ways.”

Many of those who are active on the platform are unwilling to express themselves in the same way outside the walled-garden of a particular server. Here’s what journalists should consider before setting up a Discord profile:

Some gaming enthusiasts I spoke to recommended finding some buddies who could act as digital surrogates to connect journalists with users in noteworthy servers. As with many platforms, it’s possible to join a number of communities and to lurk and observe the chat there without conversing or publishing anything, though some moderators will pose questions and require you to link to your phone number or Reddit profile for verification before allowing you to enter.

It’s also important, as Friedberg pointed out, to jump on a VPN and post occasionally to some servers you’ve joined to avoid being kicked out. All local beats require attention, and this is no exception. An active profile will likely lead to more meaningful connections, to invitations to new groups and servers, and potentially new insight on topical stories too. You need to ask, though, how far you’re willing to dig, and whether your journalism justifies the creation of an alternative but verified profile.

Nextdoor is an opportunity for journalists to keep an eye on a local beat. Being a newbie in Cambridge for five weeks starting last month, one of the first things I decided was to try and get to know my neighbors via the local social network Nextdoor. The platform launched in the U.S. in 2011 and is used in 86 percent of U.S. neighborhoods, but more recently has expanded into Europe (the Netherlands, U.K., Germany, and France) and is now active in 185,000 neighborhoods globally, with ambitions to move into other parts of the world too. (The platform has had to revise its community guidelines following complaints about racial profiling and discrimination from some members.)

To gain entry to your neighborhood network, you need to use your real name and physical address but don’t need to say much more about yourself if you’re not inclined. Once inside, I quickly found advice about local plumbers, gardeners, the real estate market, updates from Cambridge police, and day-to-day posts from residents looking to buy and sell items. But there were plenty of other things that caught my eye: neighbors talking about local issues, burglaries, and even the occasional political conversation.

The attraction of Nextdoor is that it’s hyperlocal, visible only to those in defined geographical neighborhoods. It provides journalists with a contact book and portal into local feelings and attitudes on a range of subject, and includes feeds from news providers and several thousand public agencies too (police, fire, weather, and so forth). Participants can chat with a neighbor or respond to a news article.

The attraction of Nextdoor is that it’s hyperlocal, visible only to those in defined geographical neighborhoods. It provides journalists with a contact book and portal into local feelings and attitudes on a range of subject, and includes feeds from news providers and several thousand public agencies too (police, fire, weather, and so forth). Participants can chat with a neighbor or respond to a news article.

Nextdoor’s moderators, or “leads,” are all local volunteers. They’re provided with training and 24/7 support and decisions on permissible activity and posts are down to them and their interpretation of the community guidelines. Nextdoor permits and encourages “civil and respectful” discussion about local ballots or elections and suggest in their guidelines that members “create a group” within their neighborhood feed “to discuss national or state politics and other non-local campaign topics” — another avenue of opportunity for journalists in any given area to test the waters on a wider subject.

Nextdoor’s moderators, or “leads,” are all local volunteers. They’re provided with training and 24/7 support and decisions on permissible activity and posts are down to them and their interpretation of the community guidelines. Nextdoor permits and encourages “civil and respectful” discussion about local ballots or elections and suggest in their guidelines that members “create a group” within their neighborhood feed “to discuss national or state politics and other non-local campaign topics” — another avenue of opportunity for journalists in any given area to test the waters on a wider subject.