The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

— The top recommendations were consistently identical for conservatives and liberals

— 41 publishers (99.9 percent of recommendations) reached both conservatives and liberals

— On average, 69 percent of all recommendations were to five news organizations

— The most-recommended five publishers accounted for 49 percent of the links collected.

The research, using MTurk, was conducted before Google redesigned Google News this past spring; “since May 2018, the platform also offers a service of customized five story news briefings; yet Google News said that the top two stories will be identical for all users, and only the bottom three personalized.”

That’s not to say that there was no customization whatsoever:

Searchers of various political leanings, across the country, were offered a largely unified body of news from a small number of national publications. Neither ideological bias nor geographic bias were evident in the search results. And, when controlling for other individual-level variables, such as gender, age and location, no significant differences were evident in the news recommended to different participants.

A certain degree of personalization was identified in a minuscule subset of the results. In the first experiment, only conservatives were recommended stories from Fox News, and only liberals were recommended stories from The Daily Mail, New York Daily News, Salon and The Daily Beast. In the second experiment, only conservatives were recommended stories from The New York Post, Business Insider, and Jezebel, and only liberals were recommended stories from The Washington Times, People, U.S. News & World Report and US Weekly. These results were counterintuitive and in fact contradict the typical concern over filter bubbles: While The New York Post is known to lean right, Jezebel is anything but conservative in its politics, and likewise The Washington Times is anything but targeting liberals. Either way, the differences were marginal, representing less than 0.01% of the data collected.

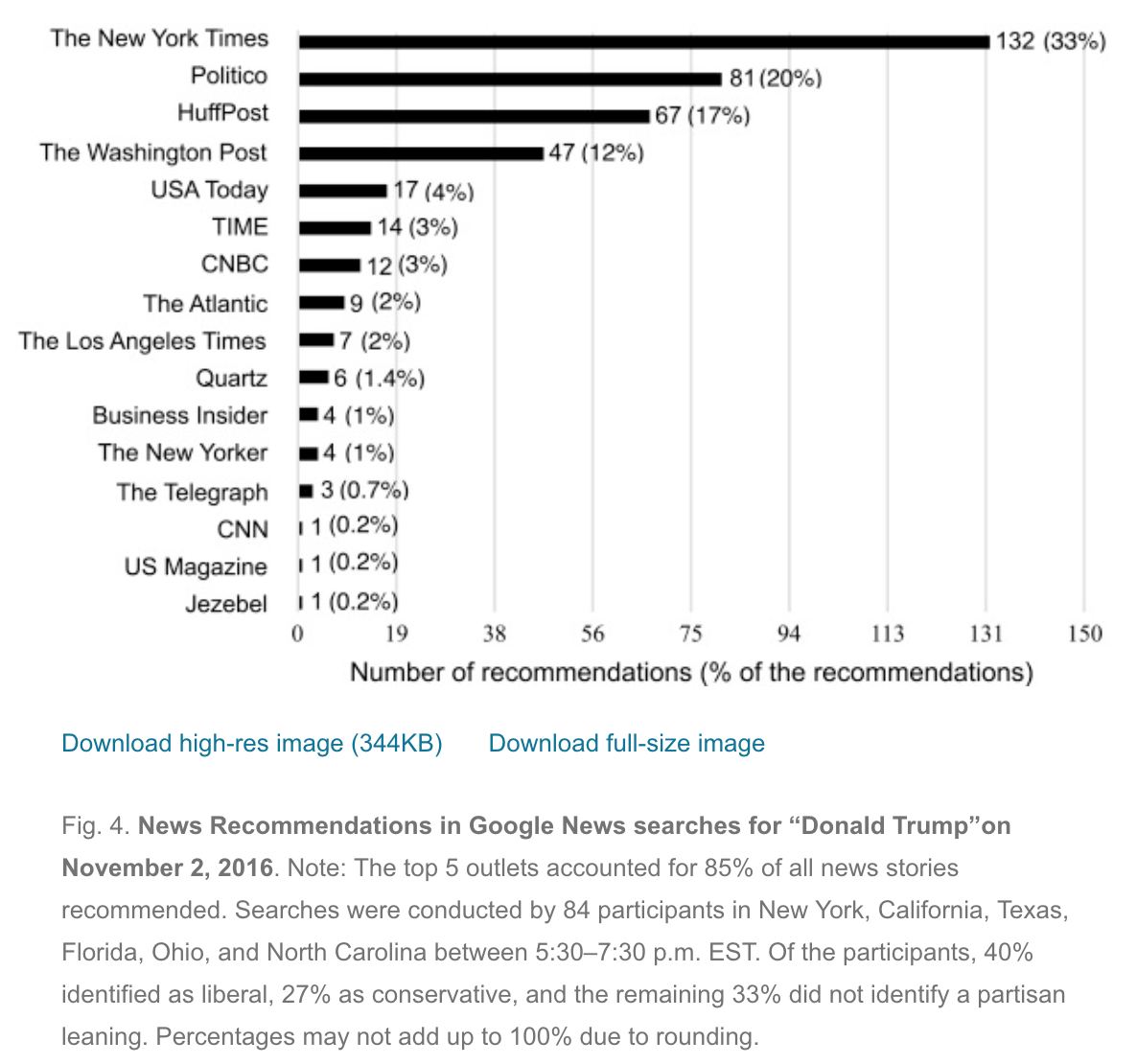

Note that mention of news “from a small number of national publications.” Here’s what respondents were seeing:

Across the four searches, fourteen news organizations ranked in the top five: CNN, Politico, Fortune, The Chicago Tribune, Business Insider, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, CNBC, ABC, Time, The Los Angeles Times, HuffPost, and USA Today. Together, these outlets made up 79 percent of the total number of news recommendations suggested to searchers.

The number of recommendations was unevenly distributed among these organizations as well, with the five most prominent outlets — The New York Times, CNN, Politico, The Washington Post and HuffPost — making up half (49 percent) of the 1,653 total recommended links. In other words, while Google News indexes many thousands of English-language news sources, every time our participants searched for news, they had a 49% chance of being directed to one of these five outlets.

There is some degree of diversity among the fourteen news organizations that occupied the top spots in the two experiments. Some are legacy print media, some are digital-native, and others are television networks and magazines. Some are general interest outlets, and others are focused on the political world. But almost all of them are large national organizations, and 79 percent of them are based in only two metro areas: New York City and Washington, D.C. (with the exceptions headquartered in the Atlanta, Chicago, and Los Angeles areas). These findings indicate that more than dissecting the public conversation into fragmented silos, digital distribution of news might narrow the conversation around a small set of national outlets.

Facebook fails to combat hate speech in Myanmar. For Reuters, Steve Stecklow investigated how Facebook is dealing with hate speech in Myanmar — and in the process of doing so, turned up more than 1,000 posts, comments and pornographic images attacking the Rohingya and other Muslims. All of these posts, in case it needs to be said, violate Facebook’s hate speech policy; some of the posts Reuters found had been on the site for as long as six years, and Reuters extensively documents the many, many warnings Facebook has received from many concerned experts in the space. Some bits from its investigation:

— “In early 2015, there were only two people at Facebook who could speak Burmese reviewing problematic posts. Before that, most of the people reviewing Burmese content spoke English.” Facebook hired its first two Burmese speakers, based in Manila, three years ago; as of June, Facebook’s about 60 people were reviewing reports of hate speech in Myanmar, which has 18 million active Facebook users. The moderation work is largely outsourced.

— Burmese mobile phone operators let users use Facebook without paying data charges, and “in Myanmar today, the government itself uses Facebook to make major announcements, including the resignation of the president in March.”

— How this is hard:

Many of the millions of items flagged globally each week — including violent diatribes and lurid sexual imagery — are detected by automated systems, Facebook says. But a company official acknowledged to Reuters that its systems have difficulty interpreting Burmese script because of the way the fonts are often rendered on computer screens, making it difficult to identify racial slurs and other hate speech.

Facebook’s troubles are evident in a new feature that allows users to translate Burmese content into English. Consider a post Reuters found from August of last year.

In Burmese, the post says: “Kill all the kalars that you see in Myanmar; none of them should be left alive.”

Facebook’s translation into English: “I shouldn’t have a rainbow in Myanmar.”

In response, Facebook said: “Our translations team is actively working on new ways to ensure that translations are accurate.” The company said it uses a different system to detect hate speech.

After the report came out, Facebook responded and said that it’s hiring more Burmese speakers.