“It will probably be all video.”

In June 2016, Nicola Mendelsohn, Facebook’s VP for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, spent several minutes of a panel at a Fortune conference talking about how Facebook was witnessing video overtake text.

“We’re seeing a year-on-year decline on text,” Mendelsohn answered. “We’re seeing a massive increase, as I’ve said, on both pictures and video. So I think, yeah, if I was having a bet, I would say: Video, video, video.”

“Wow,” the moderator, Pattie Sellers, responded.

“The best way to tell stories, in this world where so much information is coming at us, actually is video,” Mendelsohn continued. “It commands so much more information in a much quicker period. So actually, the trend helps us to digest more of the information, in a quicker way.”

“Five years to all video” wasn’t just Mendelsohn’s line — it came from Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg himself. “We’re entering this new golden age of video,” Zuckerberg told BuzzFeed News in April 2016. “I wouldn’t be surprised if you fast-forward five years and most of the content that people see on Facebook and are sharing on a day-to-day basis is video.”

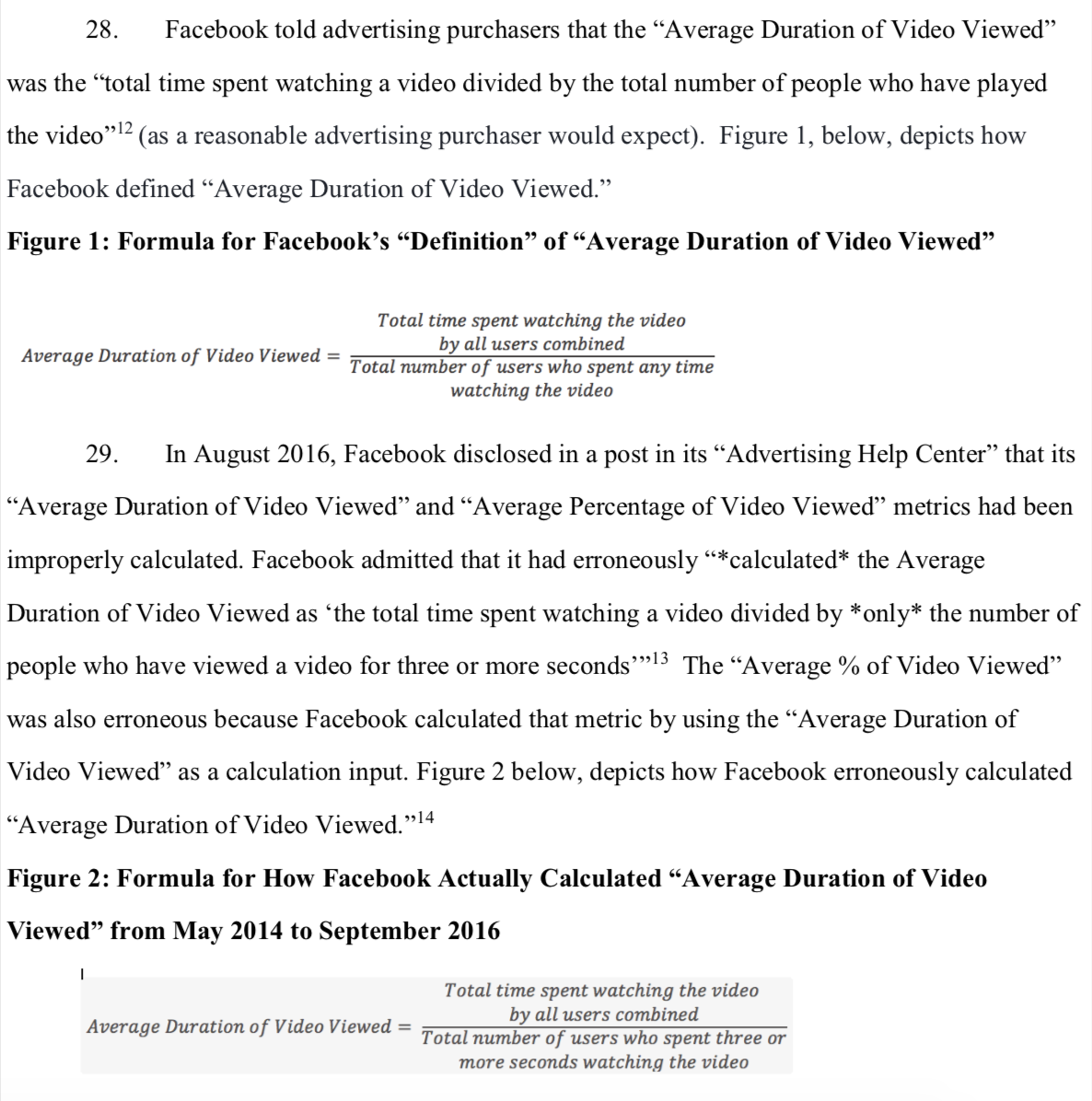

But even as Facebook executives were insisting publicly that video consumption was skyrocketing, it was becoming clear that some of the metrics the company had used to calculate time spent on videos were wrong. The Wall Street Journal reported in September 2016, three months after the Fortune panel, that Facebook had “vastly overestimated average viewing time for video ads on its platform for two years” by as much as “60 to 80 percent.” The company apologized in a blog post: “As soon as we discovered the discrepancy, we fixed it.”

A lawsuit filed by a group of small advertisers in California, however, argues that Facebook had known about the discrepancy for at least a year — and behaved fraudulently by failing to disclose it.

If that is true, it may have had enormous consequences — not just for advertisers deciding to shift resources from television to Facebook, but also for news organizations, which were grappling with how to allocate editorial staff and what kinds of content creation to prioritize. News publishers’ “pivot to video” was driven largely by a belief that if Facebook was seeing users, in massive numbers, shift to video from text, the trend must be real for news video too — even if people within those publishers doubted the trend based on their own experiences, and even as research conducted by outside organizations continued to suggest that the video trend was overblown and that news readers preferred text. (Heidi N. Moore put many of these trends together in 2017, and her accounting is only strengthened by the new information that we’re seeing this week.)The court case was unsealed this week, following efforts by organizations like the online publishers’ trade organization Digital Content Next to make previously redacted parts available to the public. I read the filing and pulled out some of the most interesting and relevant parts for news publishers below. I wanted to try to see whether Facebook’s active promotion of its video offerings might have influenced news publishers’ allocations of resources, and whether it is reasonable to allege that Facebook knew, as publisher after publisher laid off editorial staff and pushed into video, that that was misguided. I wanted to know whether people working in news organizations were fired based on faulty data provided by a giant platform that publishers believed they could trust.

We may not be able to pinpoint exactly what Facebook knew when. We don’t know all the factors that went into individual publishers’ decisions to pivot to video; we can’t see their individual analytics, what they had confirmed by third-party sources versus what they were only getting from Facebook. And it’s impossible to separate out how much of that pivot was a desperate move made at a time when things were already bad, from how much the pivot itself made things worse.

What does seem clear now is that Facebook’s executives’ statements about video should not have been a factor in news publishers’ decisions to lay off their editorial staffs. But it’s hard not to conclude that publishers heard that rhapsodizing about the future and assumed that Facebook knew better than they did, that Facebook’s data must be more accurate than their own data was, that Facebook was perceiving something that they could not. That their own eyes were wrong.

One thing to keep in mind as you read the below: Facebook employees are quoted, but the quotes aren’t attributed. Without viewing the source emails or reports, we don’t know the context of what was said, and we don’t know who, for instance, said the company decided to “obfuscate the fact that we screwed up the math” — was it a junior coder or (probably not) Mark Zuckerberg? We don’t know from the filing how far up the food chain the discussion of errors went.

For its part, Facebook told me in a statement, “This lawsuit is without merit and we’ve filed a motion to dismiss these claims of fraud. Suggestions that we in any way tried to hide this issue from our partners are false. We told our customers about the error when we discovered it — and updated our help center to explain the issue.”

Here are some of the most interesting parts of the court filings.

— The lawsuit alleges that “Facebook engineers knew for over a year” that the company’s metrics were “overstating the average time its users spent watching paid video advertisements,” and that “multiple advertisers had reported aberrant results caused by the miscalculation (such as 100% watch times for their video ads.”

Facebook told me that it told clients about the errors, that the clients didn’t say anything until a memo leaked to The Wall Street Journal, and that clients didn’t care about the error because it was not billable.

— The Wall Street Journal had reported that viewership metrics were inflated by “60 to 80 percent,” figures that Facebook did not dispute. The lawsuit, however, alleges that the metrics were inflated by much more — “some 150 to 900 percent.” When Facebook “summarized the impact of the miscalculation internally,” for instance, it allegedly presented “two typical cases”:

In one, Facebook had inflated Average Duration of Video Viewed from 2.0 seconds to 17.5 seconds (an increase of 775%); in the other, Facebook had inflated Average Duration of Video Viewed from 2.4 seconds to 17.3 seconds (an increase of 621%).

— The suit alleges that there was a long lag between the time that the engineers realized the metrics were faulty and the time that Facebook corrected them, due to understaffing on the engineering team, and that

Even once Facebook decided to correct the false metrics, it chose not to do so immediately. Instead, Facebook chose to continue disseminating false metrics for several more months while it developed and deployed a ‘no PR’ strategy designed to ‘obfuscate the fact that we screwed up the math.’ All the while, Facebook continued to reap the benefits from the inflated numbers.

Facebook denied that it knew in advance about the particular calculation error that was discovered in summer 2016, and told me the plaintiffs mischaracterized the documents and took them out of context.

— This was Facebook’s actual error: It divided total time spent watching a video not by the total number of users who spent any time watching the video (a group that would have included people “quickly scrolling past muted auto-playing video advertisements”), but instead by only the number of users who watched a video for three seconds or more. The result: “A highly misleading result that favored Facebook.”

— In an previous instance, Facebook allegedly also chose not to correct faulty metrics immediately.

What does “user trust” mean here? It is unlikely that everyday Facebook users would notice or care much about video viewing metrics; it makes more sense to read “users” as advertisers and publishers, i.e., companies using Facebook to promote their content.

“We know we can’t have true partnerships with our clients unless we are upfront and honest with them,” David Fischer, Facebook’s VP of business and marketing partnerships, wrote in that September 2016 blog post.

Raise your hand if you were ever in a mtg thinking to yourself “really? Video? I hate video! I never watch video!” And then deciding you must be old and washed bc data https://t.co/SoJrJHpqUq

— Emily Yoshida (@emilyyoshida) October 17, 2018

It’s impossible to say whether media executives felt the way we did, or whether they actually did watch a lot of news video and truly believed it was the future. What is clear, however, is that plenty of news publishers made major editorial decisions and laid off writers based on what they believed to be unstoppable trends that would apply to the news business:

— Mic (August 2017): “We made these tough decisions because we believe deeply in our vision to make Mic the leader in visual journalism and we need to focus the company to deliver on our mission.” [Facebook’s Mendelsohn, 2015: “Visual communication allows us to sustain the break-neck pace of modern life in a world where we’re sending nearly four billion emails a day and checking our phones at least four times an hour…We couldn’t handle all this information if an increasingly large part of it wasn’t visual.”]

— Vice (July 2017): “Vice Media is laying off about 2 percent of its 3,000 employees across multiple departments while at the same time the company is looking expand internationally and ramp up video production.”

“Cutting jobs is necessary to put more resources into video production, a Vice spokesman said.”

— MTV News, June 2017: “While we’re proud of the longform editorial work from the past two years, we’re returning the editorial operation to its roots of amplifying the audiences’ voices and shifting resources into short-form video content more in line with young people’s media consumption habits.”

— Fox Sports, June 2017: “We will be shifting our resources and business model away from written content and instead focus on our fans’ growing appetite for premium video across all platforms.”

— Vocativ, June 2017: “We’ve seen a shift in digital publishing in favor of distribution on social media and other platforms, along with a dramatic increase in demand for captivating video content…Today, we are announcing that Vocativ will shift to an all-video format…This means that we will be phasing out written stories.”

— Bleacher Report, February 2017: “A majority of the cuts were within the editorial operations department…With Bleacher Report investing more on higher-quality content, including original video and prominent writers like Howard Beck, these positions were no longer necessary to the company.”

— Mashable, April 2016: “We are now equally adept at telling stories in text and video, and those stories now live on social networks, over-the-top services and TV. Our ads live there too, with branded content now at the center of our ad offering. To reflect these changes, we must organize our teams in a different way. Unfortunately this has led us to a very tough decision. Today we must part ways with some of our colleagues in order to focus our efforts.”

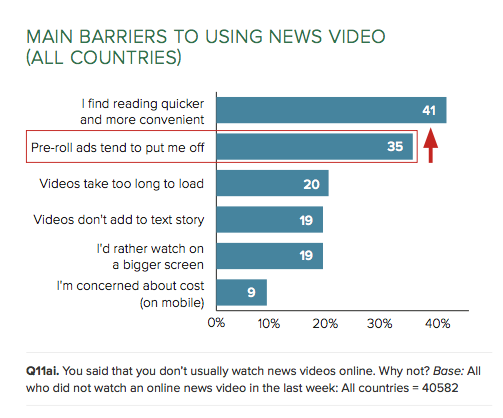

Even as publishers were making these pronouncements, however, outside research often didn’t back up their claims that news consumers craved video or preferred it to text. Take this report from The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in the summer of 2016:Analyzing Chartbeat data from 30 news outlets across the U.S., U.K., Germany, and Italy (17 of the outlets were American, nine were broadcasters), the researchers found that the sites’ users spent ‘only around 2.5 percent of average visit time’ on pages that included videos, and ‘97.5 percent of time is still spent with text.’ That 2.5 percent of time spent was even lower than the total share of pages that have videos (6.5 percent)…

‘So far, the growth around online video news seems to be largely driven by technology, platforms, and publishers rather than by strong consumer demand,’ Antonis Kalogeropoulos, one of the report’s authors, said in a statement.

Or more research from Reuters in 2016:

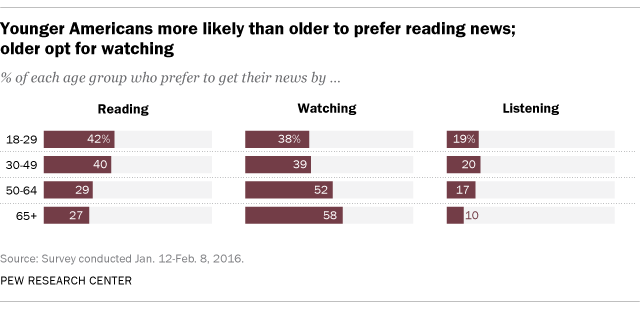

Or here’s Pew in 2016, suggesting that the fears we just weren’t young enough to get it were unfounded:

“When asked whether one prefers to read, watch or listen to their news, younger adults are far more likely than older ones to opt for text, and most of that reading takes place on the web.”

Or this report from analytics firm Parse.ly in January 2017:

Parse.ly examined the performance of four types of posts within its network of 700 sites: long-form, short-form, video, and slideshows. Video posts received 30 percent less engaged time than the average post, the study found.

“I don’t want writers to go out of business,” Fortune’s Sellers said at that panel in 2016.

“You have to write for the video,” Mendelsohn pointed out.