If you spend dozens of hours learning about a subject — say, government procurements — for an article, you might want to find some way to use that knowledge beyond just hitting Publish on a story.

As a journalist, obviously, there are some hesitations; the debate on where the line falls between journalism and activism continues to simmer. But the activist-for-truth role of a journalist is part of the core of Spanish nonprofit news organization Civio, which believes that when it uncovers problems in government, part of its job is to lobby for specific solutions.

Eva Belmonte, Civio’s managing editor, has shown up at Spanish legislators’ offices with 100-page proposed amendments in tow. Some of her legislative language has made it into Spanish law. After reporting extensively on the procurement process, Belmonte became Civio’s main outreach to government officials.

CIvio doesn’t lobby on every issue it reports on. But if its reporting shows that the government is standing in the way of transparency or accountability, it’s not afraid to take a stand.

“You know so much of the problems you have implementing the law, what kind of information you need to try to avoid corruption or similar,” she said. “You feel all this knowledge would be useful for something, for trying to change something.”

Belmonte, an eight-veteran of the newspaper El Mundo, joined the then-two-year-old Civio in 2013. The group, founded by software developer David Cabo and entrepreneur Jacobo Elosua, modeled itself after the Sunlight Foundation and pushed for open data practices and tools to help citizens see the intricacies of public institutions. Civio pivoted to add journalism as a core component (yes, a pivot to journalism!) to help tell stories from the data a few years later, taking inspiration from ProPublica this time. Now it has a staff of four journalists and two or three (if you count Cabo) tech folks in its Madrid office.

“The whole narrative was naive — a tech utopia. We realized we needed to have lobbying to make things work and the journalism was very important to us,” Cabo, Civio’s executive director, said. “Now, we are a nonprofit investigative newsroom with a strong technical angle, because we still have tech skills, but are now focused very much in data journalism.”

Many of its lobbying efforts have been prompted by that need for public data to fuel its journalism. “Very quickly we realized we didn’t have an access-to-information law like FOIA,” Cabo said. “Many of the investigations we couldn’t do because there was no public data available. We realized we had to push for that.”

In its seven years, Civio has reported on the details of daily government bulletins, closely tracked 10,000 pardons from the past 20 years (building its own Pardonmeter with scraped results), and investigated pharmaceutical pricing differences and access worldwide. It’s very close to convincing public officials to make their daily meeting schedules public for transparency, Cabo and Belmonte told me.

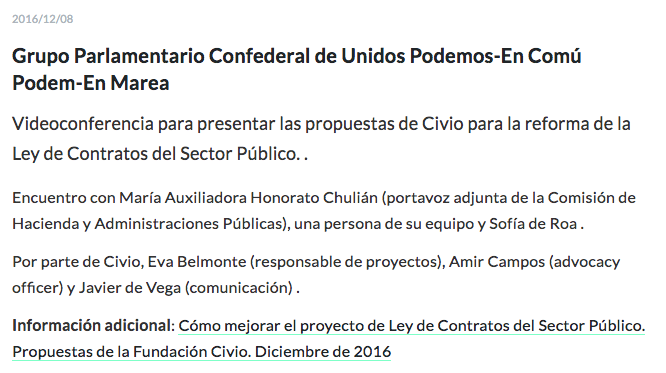

Civio is upfront with readers about their lobbying every step of the way, with their goals, recommendations, and even a running list dating back to 2015 of which officials they met with when and what their intentions were. An example:

(In English, this entry talks about a video conference Civio held with the deputy spokesperson of the Finance and Public Administration Commission in order to present proposals for public-sector contract reform, identifying the members of the meeting from Civio and the government.)

“Every meeting we have — we talk about it, publish the documents we use in those meetings,” Cabo said. “We thought it was the right way to show it can be done.”

But as a nonprofit newsroom, the team is limited by the lack of a major philanthropy-in-news culture like the one the U.S. has spent the past decade been cultivating.

Only 2 percent of Spaniards currently donate to news organizations, but 28 percent told researchers with the Reuters Institute’s Digital News Report that they could see themselves donating in the future. (To be fair, the U.S. was only at 3 percent/26 percent on those same questions.) Independent Spanish media outlets have been experimenting with donation structures in recent years — digital news organization El Español raised €3.6 million in a 2015 crowdfunding campaign.Still, Cabo has had to become creative with Civio’s funding sources. It made money off of helping Barcelona and Madrid create visualizations of their budgets using a Civio open-source tool.

In 2017 alone, Open Society Foundation (€68,180), the European Union (€61,926), and the European Journalism Center (€16,302) have given grants for Civio to work on projects or for general operations. On the individual level, Civio has more than 400 donors — no anonymous contributions allowed — with many chipping in around 5 to 10 euros a month. Most of Civio’s readers are between ages 35 and 50, with a lot of middle-manager public officials, journalists who share Civio’s mission, and tech workers who appreciate open data efforts, Cabo said.

Civio is not the only news organization taking a more pointed approach, though again it lobbies only for issues of government transparency and lowering barriers for journalism in Spain. Schibsted created a director of public policy role earlier this year, and of course industry organizations lobby Facebook for more pieces of the pie and governments about market regulations, for example. But it’s one thing to have your work stop when readers start clicking on the story — and another to advocate fixes for the problems you’ve found.“If we are eight people and manage to do this, I don’t want to know what bigger companies are doing,” Cabo said.