The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

We’re not trapped in filter bubbles, but we like to act as if we are. Few people are in complete filter bubbles in which they only consume, say, Fox News, Matt Grossmann writes in a new report for Knight (and there’s a summary version of it on Medium here). But the “popular story of how media bubbles allegedly undermine democracy” is one that people actually seem to enjoy clinging to.

“Media choice has become more of a vehicle of political self-expression than it once was,” Grossmann writes. “Partisans therefore tend to overestimate their use of partisan outlets, while most citizens tune out political news as best they can.” We use our consumption of certain media outlets as a way of signaling who we are, even if we A) actually read across fairly broad number of sources and/or B) actually don’t read all that much political news at all. This makes sense when you think about it in contexts beyond news — food, for instance. I might enjoy identifying myself on Instagram as a foodie who drinks a lot of cold brew and makes homemade bread, but I am also currently eating at a Chic-fil-A.

Grossmann looks at two different types of studies of media consumption: Studies that ask people to name news sources they consume, and studies that actually track their news consumption behavior (by, say, recording what they do online). The results of these two types of studies are different:

The key insight is that people overreport their consumption of news and underreport its variety relative to the media consumption habits revealed through direct measurement. Partisans especially seem to report much higher rates of quintessential partisan media consumption (such as Rush Limbaugh listenership) and underreport the extent to which they use nonpartisan or ideologically misaligned outlets. People may explicitly tell interviewers they rely mostly on Fox News, while their web browsing histories and Facebook logs suggest they visit several different newspapers and CNN’s website (along with many apolitical sites).

This may seem like kind of a good thing, but don’t get too excited, says Grossmann:

Republicans are not as addicted to Fox News as they claim, nor are Democrats as reliant on Rachel Maddow as they say. But that also means partisans now think of media consumption as an expressive political act, and therefore believe that they should stick to Fox, as right-thinking Republicans, or that they should be loyal to MSNBC, as right-thinking Democrats.

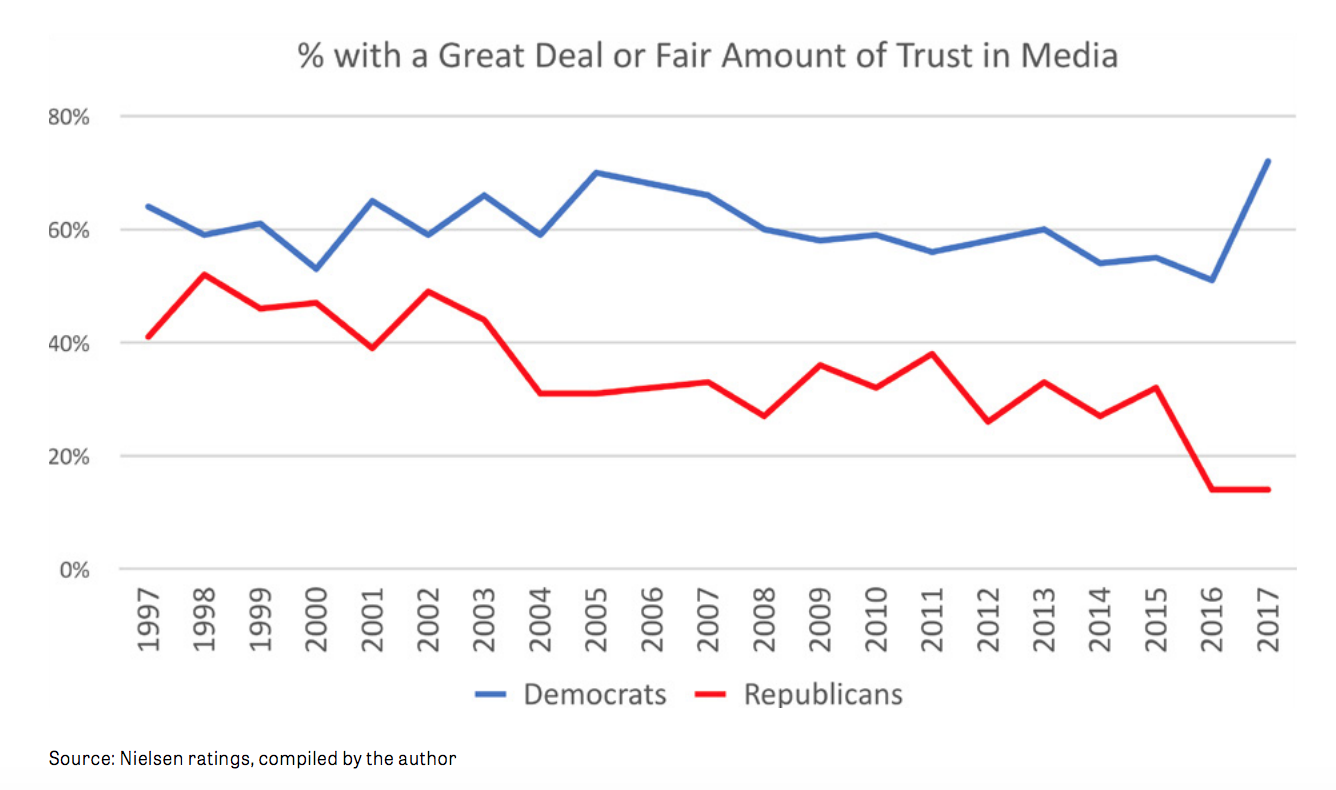

There is also some useful stuff on how partisan trust in the media has shifted: “Democratic trust in media is now higher than it has been in over 20 years, while the reverse is true for Republicans.”

“Research findings thus far do not support expansive claims about partisan media bubbles or their consequences,” Grossmann writes, though this doesn’t mean that we can totally stop worrying about this; he argues we particularly need to work on strengthening local political news, as “we have a hyperpartisan and engaged subset of Americans who consume mostly national news of all kinds,” and a more robust local media could be a useful tool in drawing in the majority of Americans who consume little to no news at all.

Different people, different Google results — but is that a filter bubble? Search engine DuckDuckGo — which, to be clear, is a Google competitor — published an examination of how Google’s search results differ by user.

We asked volunteers in the U.S. to search for “gun control”, “immigration”, and “vaccinations” (in that order) at 9pm ET on Sunday, June 24, 2018. Volunteers performed searches first in private browsing mode and logged out of Google, and then again not in private mode (i.e., in “normal” mode). We compiled 87 complete result sets — 76 on desktop and 11 on mobile. Note that we restricted the study to the U.S. because different countries have different search indexes.

The main finding was that “most people saw results unique to them, even when logged out and in private browsing mode.” This, says DuckDuckGo, is a sign that “private browsing mode and being logged out of Google offered almost zero filter bubble protection.”

But are filter bubbles really the problem here? Danny Sullivan — cofounder of SearchEngineLand and now, yep, Google’s public search liasion — argues fairly persuasively that they’re not because even DuckDuckGo users see different results.

My Duck Duck Go results compared to colleagues were also different. Again applying DDG’s own statement to itself: “With no filter bubble, one would expect to see very little variation of search result pages — nearly everyone would see the same single set of results.” pic.twitter.com/zFemD4XHj2

— Danny Sullivan (@dannysullivan) December 6, 2018

Google also responded in this thread — watch that passive voice, though.

Useful thread on what is actually going on with Google Search now. But it's disingenuous to say "a myth has developed" in passive voice. Google actively promoted the message of 'search personalized on your browsing history' when it launched, e.g. https://t.co/bDKlxnNCDJ https://t.co/gUpW179wIR

— Emma Llanso (@ellanso) December 5, 2018

Over the years, a myth has developed that Google Search personalizes so much that for the same query, different people might get significantly different results from each other. This isn’t the case. Results can differ, but usually for non-personalized reasons. Let’s explore…

— Google SearchLiaison (@searchliaison) December 4, 2018

I don't think this is saying "Filter bubble" as much as saying "Google is damn nondeterministic on controversial topics"https://t.co/ppYslNDuZm

— Nicholas Weaver (@ncweaver) December 5, 2018

In particular, the conversation often begins and ends with concerns around the filter bubble. I think many of the discussions in Silicon Valley are overly fixated on filter bubble concerns- while in the academic lit the filter bubble has often not stood up to empirical scrutiny.

— David Lazer (@davidlazer) December 5, 2018

It's not clear that a pizza-optimized search engine is optimal for the broader public sphere.

— David Lazer (@davidlazer) December 5, 2018