Some 50 newspaper executives met in Reston, Va., Friday for the American Press Institute’s “Summit on Saving an Industry in Crisis.” McClatchy, Hearst, E.W. Scripps, and The New York Times Co. were there, along with many others. Did anything come of it? Well, they agreed to reconvene in six months, but media blogger Steve Outing doesn’t think they have that long.

Chuck Peters, the chief executive of The Gazette Company in Eastern Iowa, liveblogged the otherwise-closed-door summit, which attracted comments from new-media gadflies, including Jeff Jarvis and Michelle McClellan. From the looks of that account and the API’s summary of the meeting, however, the newspaper executives didn’t get far beyond acknowledging their industry’s systemic problems. Perhaps, as Mark Potts said while the summit was still in progress, “the wrong people are in the room.”

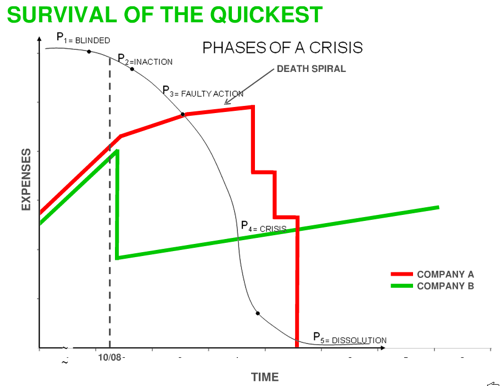

Turnaround specialist James Shein did present a frightful chart that portrayed newspapers on a rapidly plummeting roller coaster. It reminded me of a slide that Nick Denton highlighted from Sequoia Capital’s advice for surviving the economic downturn. Since they’re both plotted over time, I’ve laid them on top of each other to make a point:

Shein’s Thunder Mountain ride to oblivion (the thin black line) isn’t inevitable, at least not for everyone. But getting off that track requires a change in cash flow — more revenue, fewer expenses. So here’s one problem: Newspaper executives seem to think they can increase revenue in this climate, when ads sales are declining both in print and online. Many talk of finding new revenue streams in social networking, data collection, and subscription services. But even if there is fruit on those trees, it’s a long way from summer, and the colored lines on that chart are saying expenses need to be cut dramatically yesterday (green) or else troubled companies will fall into a death spiral (red). When your stock is “worthless” — a label recently slapped on McClatchy and GateHouse Media — the best you can hope to do is take a dive and pray the water isn’t shallow. (Apologies for all the metaphors in this graf. Reality is easier to confront when it’s coated in similtude — thus, The New York Times comparing newspapers to bicycles and Circuit City.)

This imperative for cost-cutting is why, of course, most American media companies are gutting their newsrooms, a practice that Shein notably discouraged at the API summit. There are no easy answers here, but I think more insight was to be had last week in Monte Carlo than in Reston. That was the site of the Monaco Media Forum, which has posted a bunch of videos from the conference on YouTube. The one to watch is the keynote by Jeffrey Cole, director of the USC Annenberg Center for the Digital Future. (It’s embedded below.) He said:

Traditionally a big-city newspaper, whether The London Times, The New York Times, the Globe and Mail in Canada, traditionally 70 percent of a big-city newspaper has been advertising. There will never come a day that 70 percent of thenewyorktimes.com will be advertising. But while their revenues from advertising may be smaller, they also — if you look at a newspaper’s budget, only 30 percent of it goes to editorial, goes to writers and editors. Seventy percent of it goes to printing and distribution, and those costs almost disappear in a digital world.

When drastic cuts are required, it seems crazy to focus them on the minority portion of one’s business. Maybe a few newspaper executives who saw Shein’s crisis curve on Friday and are seeking to follow Sequoia’s survival model will be frightened enough to consider taking a chunk out of the printing and distribution side of their expenses by getting out of print, in whole or in part. There are many downsides and risks to that move, of course, but as one attendee at the API summit said, “We have nothing to lose.”

Here’s the full video of Cole’s speech:

[Hello, readers from Romenesko, and welcome to the newly launched Nieman Journalism Lab. We hope you’ll come back every weekday for reporting, commentary, and conversation about the future of journalism. Here’s our front page, here’s more about us, and here’s our RSS feed.]