Newspapers have long viewed themselves as a kind of virtual public space — a place for community members to trade information and learn about each other. New media, however, has largely thrived on specialization: think clubhouses, not the town square.

With a $40,000 grant from the Knight News Challenge, Boston artist John Ewing hopes to reverse that thinking, using digital technology to stimulate old-school public dialogue. It’s a vision of the media as “context providers,” not “content providers,” as Ewing told me over email.

With a $40,000 grant from the Knight News Challenge, Boston artist John Ewing hopes to reverse that thinking, using digital technology to stimulate old-school public dialogue. It’s a vision of the media as “context providers,” not “content providers,” as Ewing told me over email.

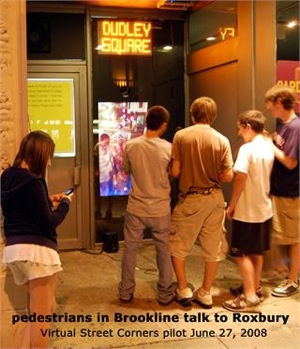

His Virtual Street Corners project will install large storefront video screens connecting two very different Boston neighborhoods, Brookline and Roxbury. These “portals” will give residents of each town a real-time way to talk, argue, share news, or simply watch each other. Video and podcasts of what happens on the screens will be available for download onto the mobile phones of passersby. Ewing said the information shared via the digital screens will be personal and only possibly factual — a real-life Twitter, if you will.

While Ewing sees Virtual Street Corners as a complement to Roxbury and Brookline’s existing community papers, the project is also designed to bridge racial and class barriers that newspapers have often failed to overcome.

At first glance, Ewing’s art project may not seem particularly journalistic; one Knight News Challenge judge called the project “very unKNC,” while others called it the “least newspapery” of the contest’s finalists and a “fun” idea that “probably doesn’t fit into the KNC.”

But the art project that aimed to bring social media back into the physical realm won anyway. As one journalist at the conference told Ewing: “I love this project because the street corner is where news happens.”

Although they’re only 2.4 miles apart, there’s little interaction between Roxbury, “the heart of black culture in Boston,” and Brookline, a neighborhood that’s largely white, upper-middle class, and Jewish. When he asked 25 residents from each neighborhood to map their routes through the city each day, Ewing found that there were almost no overlaps between the two communities.

Although they’re only 2.4 miles apart, there’s little interaction between Roxbury, “the heart of black culture in Boston,” and Brookline, a neighborhood that’s largely white, upper-middle class, and Jewish. When he asked 25 residents from each neighborhood to map their routes through the city each day, Ewing found that there were almost no overlaps between the two communities.

“Traditional news media tends to be more representative of economically advantaged communities,” Ewing wrote in his application. “Virtual Street Corners relies on new technology, interpersonal contact and citizen journalism to carry news across these social divides.”

During a trial run of the project in 2008, Ewing used a series of events to get residents from the two towns talking to each other — including a back-and-forth between Roxbury City Councilor Chuck Turner and Rabbi Hillel Levine and a show by Ron Jones and Larry Tish of The Black Jew Dialogues. With the Knight money, Ewing will supplement scheduled events by hiring six citizen journalists to give regularly scheduled news updates.

“I would like to hire people who live in the neighborhoods but from different demographics, to help bring a variety of perspectives,” Ewing wrote over email. “I will choose them based on their skill in delivery and ability to acquire news. I would think that a news background would be helpful, but not necessary.” (No word yet on how much these citizen journos will be paid.)

During the test-run of the project in front of the Brookline Booksmith in June 2008, the Boston Phoenix noted predictable kinds of public engagement with the screens: kids had the most fun with them, and some prejudices came to light:

“Why would anyone want to see what Roxbury is doing?” a white man in a too-tight T-shirt asked a woman standing nearby. “Why put it in Dudley, why not Harvard Square? People are smart there. All you’re gonna see there is crime.” After the man left, the woman called him a racist.

Ewing’s goal is to replicate the kind of news sharing that he has experienced working on his different public artworks “while standing on various street corners around Boston.”

“[M]any people came up to talk to me,” he wrote. “People from all walks of life, offering their opinions, their experiences, gossip, crime stories, love stories, theories of economics, race relations etc. and it was usually delivered with a flair particular to that neighborhood. It may or may not have been factually correct.”

As a RISD-trained artist interested in “dialogic public art,” Ewing said that he works in the tradition of British artist Peter Dunn, who described public artists as “context providers” instead of “content providers.” It’s a distinction that can apply as usefully to the news business as to the arts.

While creating community interaction with digital screens is an old idea — dating back to Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz’s 1980 Hole in Space between L.A. and New York — Ewing noted his project was unique in using technology not to bridge huge geographic or cultural gaps, but the narrow social divides of a segregated American city. Ewing originally planned to use digital screens to link Ramallah, Tel Aviv, and New York, but decided to start closer to home when logistical difficulties stymied that project, he told the Phoenix last year. The Ramallah/Tel Aviv/New York link may still be in the future — along with a similar project connecting Havana and Miami.