[The Internet opens up new means of communications for major NGOs. But does it also make their position vulnerable to a new breed of web-native upstarts, who understand the power of technology more fully? Denise Searle, who has worked with some of the world’s best known NGOs, explores that in this, the final part of our series on NGOs and the news. —Josh]

At the offices of the Daily and Sunday Telegraph in London during December 2008, the customary Christmas and New Year parties were supplemented by a round of often tearful farewell drinks as staff at the respected broadsheet newspapers reeled from the third round of redundancies in two years. The Telegraph Media Group’s desire to invest in its online activities was a key reason for the cuts in print journalist jobs, with the global economic downturn adding to the pressures.

The Telegraph is far from alone. Most UK and U.S. newspapers and news broadcasters have been building up their online presence, which has usually involved spreading editorial resources more thinly to create round-the-clock multimedia online outputs from existing or even reduced staff complements. In January 2009, the Los Angeles Times announced that it was axing 300 jobs, 70 of them in the editorial department, which had already been virtually halved in size over the past five years. The timing was surprising. According to Jeff Jarvis, journalism professor at the City University of New York and writing in The Guardian newspaper, the LA Times editor, Russ Stanton, had claimed earlier that month that the paper’s online advertising revenue was sufficient to cover the entire print and online editorial payroll.

There is growing concern about the combined effect on news coverage of financial pressures and the needs of the internet. In January 2008, the UK and Ireland’s National Union of Journalists sent out an e-alert to members asking them to blow the whistle on where cutbacks are undermining journalism standards.1 The same month the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University published “What’s Happening to Our News: An Investigation into the Likely Impact of the Digital Revolution on the Economics of News Publishing in the UK.” International news is particularly vulnerable because it’s costly. According to the Reuters Institute report, there has been a large-scale cull of foreign news staff in newspapers and broadcasters in the UK and abroad. Independent Television News (ITN), a major broadcast news provider in the UK, has more than halved the number of permanent overseas bureaux and staff since 2000. ITN now allocates just five per cent of its overall news budget to a network of six foreign bureaux.

“To feed the appetite of 24/7 media platforms, news publishers increasingly rely on a range of external suppliers for the raw material of journalism,” says the report, “not only trusted wire agencies, but also the public relations industry and, more recently, citizen journalism.” It’s safe to assume that NGOs and charities could be included in the list.

While few NGOs would celebrate the loss of jobs and the squeeze on foreign news coverage, many of those involved in international humanitarian and development work are certainly eyeing up the opportunities these changes present for increasing coverage of their concerns and activities by the media, particularly on their digital/internet platforms. International NGOs have access to human interest stories, so the logic goes, so surely the content-hungry news websites can’t afford to be as choosy as their parent publishers and broadcasters have been in the past and will snap up news and features to fill the gaps left by shrinking foreign reporting teams.

Be there or be square

The reach of the internet and associated digital platforms, such as mobile phones and online social networking sites, continues to grow. According to the Internet World Stats website, which aggregates data from the International Telecommunications Union and Nielsen/NetRatings among others, more than 1.5 billion people around the world use the internet, which is 23.4 per cent of the total global population. This has grown by 305.5 percent since 2000. The fastest expansion has been in the global south and east in recent years but even mature markets such as the United States and UK continue to grow. Almost 47 million or 76 percent of people in the UK use the internet, a growth of 203.1 percent since 2000. In the United States, 228 million people use the internet, representing 74.1 percent of the population and 138.8 percent growth since 2000.

NGOs need to engage these internet users for funds and general support, and because the people they need to influence for policy change and major donations are increasingly influenced by the internet. The internet is no longer simply an alternative or accompaniment to traditional print-based communications. Internet experts point out that many “digital natives” (usually defined as people aged 18-28, largely in industrialized countries) are uncomfortable with more traditional forms of communication. In other words, they probably won’t read the lovingly produced mail shots. Even “digital immigrants” (those over 30-ish) expect their NGO of choice to have a substantial online presence.

Plus, the internet theoretically enables NGOs to communicate directly with existing and potential supporters, without having their messages filtered by the media or the commercial prospecting agencies that many use to recruit new members or supporters via the telephone or on the street. This must be a benefit, given that the 2009 edition of the Edelman Trust Barometer (an annual international survey commissioned by Edelman Public Relations, based on 30-minute interviews with 4,475 individuals aged 25-64) showed that trust in nearly every type of news outlet and spokesperson is down from last year — apart from NGOs. In fact, NGOs are the most trusted institutions globally: 54 percent of the older part of the age group surveyed (35 to 64 year olds) trust them to do what’s right. If only NGOs could reach their publics, they’re bound to be won over by their case. Simple. Or is it?

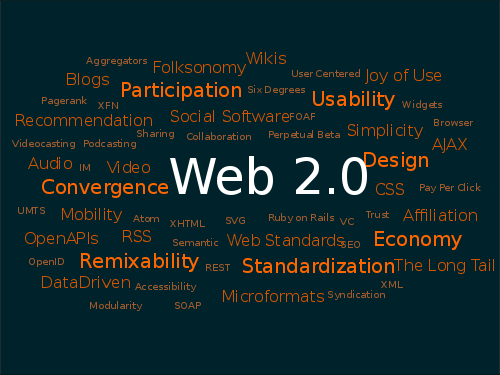

The problem is that today’s fast-moving internet isn’t an easy fit for all NGOs. In the early days, in what we now realize was merely “web 1.0,” businesses and non-profits alike used their websites as shop windows for electronic versions of the sorts of materials they published anyway. There were probably some pictures and maybe a bit of video and audio and even a “contact us” facility, but on the whole the relationship with audiences was on a “read (or watch) only” basis. Through a gradual process of increasing interactivity, “web 1.0” has morphed into “web 2.0,” which is based on participation, and where many users expect to share their own content and ideas and be listened to. The underlying technology is largely the same, but more people are using it in many different ways. Organizations that are known and respected in the real world often face competition for attention from a range of other sources and perspectives in the virtual world.

What’s more, this dynamic online environment continues to change. In July 2008, the U.S. business website Forbes.com tapped the internet analysts Nielsen Online to get a sense of where and how U.S. residents are migrating on the web. They drew up a list of the 20 most trafficked websites, compared with three years earlier, and found that the top slot went to Google, with 123 million unique visitors a month, seven million more than Yahoo, the second most popular site, and 62 per cent more than the 76 million unique visitors Google attracted three years previously, when it ranked fourth.

The survey indicates that the Internet is still about searching for information. Out of the top five sites most visited in the United States — Google, Yahoo, MSN, Microsoft’s home page, and AOL Media Network — four are portals to other websites. This means that: “web surfers are ‘leaning forward,’ looking for something in particular, versus ‘leaning back’ as browsers of traditional print publications do,” concludes Forbes.com. “In theory, that dynamic should spell opportunity for online enterprises peddling products and information that truly meet specific needs, be it t-shirts or health advice (if only it weren’t for the myriad competitors, now on similar footing, trying to do the same thing).”

The United States’s sixth most popular web destination is YouTube, the user-generated-video site, with 75 million unique visitors a month, each of whom spent an average of one hour per visit. In fact user-generated content of all sorts has redrawn the digital map. Wikipedia, the user-generated encyclopedia, jumped to 9 on the list from 57 three years ago. Online social networks are also popular, with Facebook ranking 16 on Nielsen’s list with more than 34 million unique visitors, compared with 4 million in July 2005, when it ranked 236, according to the Forbes.com article. The picture is similar in the UK, which has the highest level of online social networking in Europe.

I’m speaking but are you listening?

“We’ve only just begun the journey of involving readers,” said Alan Rusbridger, editor-in-chief of Guardian News Media, in an interview in the February 2009 edition of UK Press Gazette, in which he described the group’s move to new premises accompanied by a switch to 24/7 multimedia publishing across The Guardian, The Observer and guardian.co.uk (with no compulsory redundancies).2 The Guardian has the UK’s most popular newspaper website, with 26 million unique users a month.

“I think journalists are going to get much more at ease with the idea that we don’t know it all, and that we’ve got incredibly intelligent readers who live and breathe The Guardian and who love the opportunity to get involved with it,” Rusbridger said. “What that means in terms of the systems and how you edit and aggregate all that, I don’t know — but that’s what makes it so interesting.”

All this indicates that if humanitarian and development NGOs want to attract and retain visitors in the increasingly crowded and competitive online world, and turn them into supporters, they need to provide timely, easy-to-find information, genuinely involve their audiences, and keep up with the latest trends. This is a tall order, particularly when many of the web destinations competing for their audiences’ attention have commercial muscle behind them.

Feeding the voracious internet beast takes extensive human and technical resources. While most NGOs have established substantial web teams, they are not geared up for 24/7 content provision and updating — and probably should not be, given that their core business is in a different field, such as tackling poverty or defending human rights. Plus, the fast turnaround and response demanded by the internet (which is putting a strain on the quality of output from traditional print and broadcast newsrooms) conflicts with the longer-term, planned activities of most humanitarian and development NGOs, and simply could not be met by the lengthy approval processes most NGOs operate for any kind of external communication. The contradictions are illustrated in “Virtual Promise,” a survey published in 2008 by the UK think tank and research consultancy nfpSynergy into charities’ use of the internet. Of 376 organizations surveyed, 80 percent said they used their website for “news and regular updates” yet only 25 percent said they updated their website on a daily basis.

There’s also a difference in perspective and culture, particularly when it comes to involving supporters and giving them a voice. The big humanitarian and development NGOs work on the basis that supporters give them money and trust them to spend it wisely in working to achieve their mission. It’s genuinely difficult to decide how much information and transparency to provide around an NGO’s work and objectives, and the strategic decisions that have shaped the particular activities and approach being undertaken. How should these processes be translated for the digital sphere to make them accessible in a sound-bite culture while not being misleading over the challenges of building rural livelihoods, protecting biodiversity, ending the arms trade and so on? How much detail can internet visitors be expected to absorb?

It’s all very well having snappy, web-friendly outreach or media and commercial advertising activities that drive audiences to the website. But when people get there, very often they find that the optimistic, passionate promotional materials have dissolved into stark content about suffering, hardship, injustice, and the other myriad issues NGOs are dealing with. Or conversely, they are presented with slight web features that imply that the problems are all being dealt with.

NGOs have made real efforts over recent years to engage with the internet beyond simply building an attractive website. A visit to Facebook brings up more than 500 results for Oxfam, including pages from various Oxfam national chapters, pages on specific campaigns and links from supporters. Some are current, while others are old and/or out of date. There are similar Facebook presences for Greenpeace, Amnesty International, Save the Children, Medecins sans Frontieres and other major international NGOs. On Youtube there are 3,860 videos about Amnesty International, both official videos and those posted by supporters. [Please note that the number of videos cited was current as of the time this essay was written in 2009; the numbers today may be substantially different.] The situation is similar for Oxfam (2,460 videos), Greenpeace (12,700 videos), Save the Children (13,900 videos), and Medecins sans Frontieres/Doctors Without Borders (286 videos). NGO content on MySpace includes videos, weblinks and dedicated pages by the organizations themselves and supporters, and again the big players are there, including Greenpeace (101,000 entries); Oxfam (30,000 entries); Amnesty International (38,100 entries); Save the Children (207,000 entries); and Medecins sans Frontieres/Doctors Without Borders (around 15,000 entries).

But go to most large NGOs’ websites and it’s near impossible to find information about the volume of visitors to the website or numbers of supporters. For example, Amnesty International USA quotes 2.2 million global supporters for the total Amnesty movement but doesn’t give its own national membership (although Amnesty International UK does give its 230,000 “financial supporters”). Others don’t even do that, including Medecins sans Frontieres UK and Liberty. Oxfam GB, Save the Children UK, and Amnesty International USA give financial figures (Amnesty International USA and Save the Children UK publish their audited report and accounts). Greenpeace US provides Greenpeace International accounts. But all take some finding.

This is not very web 2.0. Digital natives and frequent internet users tend to expect more information about what an organization is doing and who else is involved to decide whether they are in good company. Peer feedback and activities are key drivers of web activity, hence the popularity of blogging and the “swarm of bees” effect that can drive huge numbers of users to view a video on YouTube or to sign up to a particular petition.

Promoting impact

The Kiva website, which enables users to give loans to businesses in the developing world via local microfinance partners, has an “Impact This Week” box on its home page that tells you how many people have made a loan in any one week, and how many new lenders there are. There’s also easy-to-find information on different lending teams, now many are in them and how much they’ve loaned. Kiva enables lenders to see the actual project they will be supporting and to monitor progress. Avaaz.org, the international civic organization that promotes activism on issues such as climate change, human rights, and religious conflicts, states at the top of its homepage how many actions have been taken since it was set up in January 2007 (15,277,937 as of January 2010). Prominently, on its “about us” page, it says: “In less than three years, we’ve grown to over 3.5 million members, and have begun to make a real impact on global politics.” The front page of the U.S. liberal public policy advocacy and political action group Moveon.org says: “Join more than 5,000,000 members online, get instant action updates and make a difference.” It also gives clear facts about actions and money in the website’s “” section.

It is obviously easier for small, single (or limited) issue groups to provide this kind of apparently transparent data than larger, more complex, long-established NGOs whose claims are likely to be more closely scrutinized by their own members as well as outside audiences and regulatory bodies. Who is going to count whether Avaaz actually has more than 3.5 million members in every nation of the world? Whereas Amnesty International spent a couple of years painstakingly compiling the returns from its 80 offices round the world before releasing the figure of 2.2 million members, supporters, and subscribers. Even so, big NGOs do have a way to go before they are truly embracing the spirit of the internet.

nfpSynergy’s 2007 fundraising benchmark survey of 109 charities showed that online fundraising raises on average just 2 percent of total voluntary income. This compares with supporter development and retention raising 27 percent of voluntary income and major donors raising 7 percent. Ironically, online fundraising is highly cost-effective, raising an average of around £10 for every £1 spent on direct costs, including salaries. “Most charities have not started to implement best practice and maximize their income. Most are missing the opportunities from both web and email communications and from the various ways of collecting online income,” wrote independent charity ICT and internet consultant, Sue Fidler, in Third Sector Magazine.

She reckoned the reasons are often simple: charities do not have the time, the resources or the knowledge to get the various tools and mechanisms in place, or the management buy-in to get more resources. But for many there is a more frustrating reason: they have the tools but are not using them to sell the charity’s proposition. If the route to donate and the ask are wrong, the tools won’t help.

“We have learnt that having a donate button isn’t enough. The concept of ‘build it and they will come’ hasn’t worked,” Fidler wrote. “Until we learn to sell ourselves online, using our stories to engage our supporters while offering them every opportunity to help, we will not see an increase in online income.”

Nick Aldridge, Chief Executive Officer of MissionFish, is slightly more optimistic. In the forward to MissionFish’s June 2008 report, “Passion, Persistence, and Partnership: the Secrets of Earning More Online,” he states that “Charities of all sizes are becoming more confident and sophisticated in using the web to attract, engage, and develop potential supporters. They are learning that success depends on the passion and persistence they show, and the strength of the partnerships they’re able to form.” User-generated content, online auctions, affinity schemes, and e-commerce are all growing in popularity.

“Those representing and speaking for charities online are finding that they need to engage the public in less formal and more personal dialogue. They must be prepared to take part in lively real-time discussions about the value of their work, rather than posting out their annual reports,” he emphasized. “It’s clear that an online strategy now involves far more than ‘click here to donate.’ Charities must recognize the difference that online interaction can make in helping them to achieve their goals, and incorporate online work in all their major initiatives.”

However, Aldridge concluded that there’s still a long way to go. “Staff who specialize in internet communications or fundraising often feel sidelined, and have a hard time explaining the potential of their work to managers. Meanwhile, many small charities still struggle to develop the tools and content they need for a basic online presence.”

Only a few years ago a senior member of the governance board of a major international NGO demanded to know who had approved the NGO’s entry in Wikipedia and why they hadn’t had it changed because the tone wasn’t as flattering as she would have liked. At that time it was pretty remarkable that she was actually aware of Wikipedia. It’s hard to envision such a conversation happening now. Yet awareness of the internet doesn’t equate to understanding or benefit. Most NGOs accept that they must exploit the potential of the digital sphere if they are to stand a chance of achieving their mission but many still believe that their core business can function as usual, which is where media organizations used to be. Websites were seen as an add-on to the main activities of publishing or broadcasting, which is now not the case, as illustrated by the current job cuts and concerns about quality of journalism.

How long will it be before international development and humanitarian NGOs see their supporter base eroded by digital native organizations such as Kiva and Avaaz, plus numerous national and local advocacy and development groups that can apparently provide digital native audiences with direct, tangible ways of making a difference? And will it stop there if governments and major institutional donors start fully embracing the internet as a way of doing business? They are already listening to online constituencies. Will these digital-savvy communities start mobilizing online to ask hard questions about why, despite years of effort, international development and humanitarian NGOs have not made poverty history or achieved social justice? And how will they be answered?

—

Denise Searle is an independent communications consultant. Her current projects include helping to develop a digital strategy for Oxfam and serving as part of the coordinating group for the communications strand of aids2031. She previously served as senior director of communications with Amnesty International and chief of UNICEF’s Internet, Broadcast and Image Section.

—