Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on the journalism-and-policy blog Lippmann Would Roll. Written by Matthew L. Schafer, the piece is a distillation of an academic study conducted by Schafer and Dr. Regina G. Lawrence, the Kevin P. Reilly Sr. chair of LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication. They have kindly given us permission to republish it here.

It’s been almost two years now since Sarah Palin published to Facebook a post about “death panels.” In a study to be presented this week at the 61st Annual International Communications Association Conference, we analyzed over 700 stories placed in the top 50 newspapers around the country.

“The America I know and love is not one in which my parents or my baby with Down Syndrome will have to stand in front of Obama’s ‘death panel’ so his bureaucrats can decide…whether they are worthy of health care,” Palin wrote at the time.

“The America I know and love is not one in which my parents or my baby with Down Syndrome will have to stand in front of Obama’s ‘death panel’ so his bureaucrats can decide…whether they are worthy of health care,” Palin wrote at the time.

Only three days later, PolitiFact, an arm of the St. Petersburg Times, published its appraisal of Palin’s comment, stating, “We agree with Palin that such a system would be evil. But it’s definitely not what President Barack Obama or any other Democrat has proposed.”

FactCheck.org, a project of the Annenburg Public Policy Center, would also debunk the claim, and PolitiFact users would later vote the death panel claim to the top spot of PolitiFact’s Lie of the Year ballot.

Despite this initial dismissal of the claim by non-partisan fact checkers, a cursory search of Google turns up 1,410,000 results, showing just how powerful social media is in a fractured media climate.

Yet, the death panel claim — as we’re sure many will remember — lived not only online, but also in the newspapers, and on cable and network television. In the current study, which ran from August 8 (the day after Palin made the claim) to September 13 (the day of the last national poll about death panels), the top 50 newspapers in the country published over 700 articles about the claim, while the nightly network news ran about 20 stories on the topic.

At the time, many commentators both in and outside of the industry offered their views on the media’s performance in debunking the death panel claim. Some lauded the media for coming out and debunking the claim, while others questioned whether it was the media’s “job” to debunk the myth at all.

“The crackling, often angry debate over health-care reform has severely tested the media’s ability to untangle a story of immense complexity,” Howard Kurtz, who was then at the Washington Post, said. “In many ways, news organizations have risen to the occasion….”

Yet, Media Matters was less impressed, at times pointing out, for example, that “the New York Times portrayed the [death panel] issue as a he said/she said debate, noting that health care reform supporters ‘deny’ this charge and call the claim ‘a myth.’ But the Times did not note, as its own reporters and columnists have previously, that such claims are indeed a myth…”

So, who was right? Did the media debunk the claim? And, if so, did they sway public opinion in the process?

Our data indicate that the mainstream news, particularly newspapers, debunked death panels early, fairly often, and in a variety of ways, though some were more direct than others. Nevertheless, a significant portion of the public accepted the claim as true or, perhaps, as “true enough.”

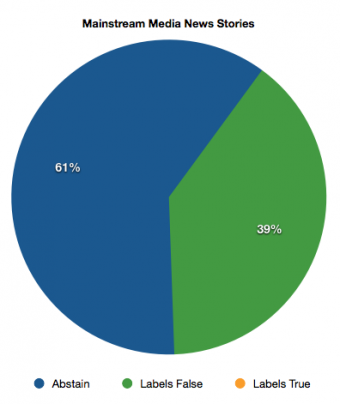

Initially, we viewed the data from 30,000 feet, and found that about 40 percent of the time journalists would call the death panel claim false in their own voice, which was especially surprising considering many journalists’ own conceptions that they act as neutral arbiters.

Initially, we viewed the data from 30,000 feet, and found that about 40 percent of the time journalists would call the death panel claim false in their own voice, which was especially surprising considering many journalists’ own conceptions that they act as neutral arbiters.

For example, on August 9, 2009, Ceci Connolly of the Washington Post said, “There are no such ‘death panels’ mentioned in any of the House bills.”

“[The death panel] charge, which has been widely disseminated, has no basis in any of the provisions of the legislative proposals under consideration,” The New York Times’ Helene Cooper wrote a few days after Connolly.

“The White House is letting Congress come up with the bill and that vacuum of information is getting filled by misinformation, such as those death panels,” Anne Thompson of NBC News said on August 11.

Nonetheless, in more than 60 percent of the cases it’s obvious that newspapers abstained from calling the death panels claim false. (We also looked at hundreds of editorials and letters to the editor, and it’s worth noting that almost 60 percent of those debunked the claim, while the rest abstained from debunking and just about 2 percent supported the claim.)

Additionally, of journalists who did debunk the claim, almost 75 percent of those articles contained no clarification as to why they were labeling the claim as false. Indeed, it was very much a “You either believe me, or you don’t” situation without contextual support.

As shown below, whether or not journalists debunked the claim, they often times approached the controversy by also quoting one side of the debate, quoting the other, and then letting the reader dissect the validity of each side’s stance. Thus, in 30 percent of cases where journalists reported in their own words that the claim was false, they nonetheless included either side’s arguments as to why their side was right. This often just confuses the reader.

This chart shows that whether journalists abstained from debunking the death panels claim or not, they still proceeded to give equal time to each side’s supporters.

Most important is the light that this study sheds on the age-old debate over the practical limitations surrounding objectivity. Indeed, questions are continually raised about whether journalists can be objective. Most recently, this led to a controversy at TechCrunch where founder Michael Arrington was left defending his disclosure policy.

“But the really important thing to remember, as a reader, is that there is no objectivity in journalism,” Arrington wrote to critics. “The guys that say they’re objective are just pretending.”

This view, however, is not entirely true. Indeed, in the study of death panels, we found two trends that could each fit under the broad banner of objectivity.

First, there is procedural objectivity — mentioned above — where journalists do their due diligence and quote competitors. Second, there is substantive objectivity, where journalists actually go beyond reflexively reporting what key political actors say to engage in verifying the accuracy of those claims for their readers or viewers.

Of course, every journalist is — to some extent — influenced by their experiences, predilections, and political preferences, but these traits do not necessarily interfere with objectively reporting verifiable fact. Indeed, it seems that journalists could practice either form of objectivity without being biased. Nonetheless, questions and worries still abound.

“The fear seems to be that going deeper—checking out the facts behind the posturing and trying to sort out who’s right and who’s wrong—is somehow not ‘objective,’ not ‘straight down the middle,” Rem Reider of the American Journalism Review wrote in 2007.

Perhaps because of this, journalists in our sample attempted to practice at the same time both types of objectivity: one which, arguably, serves the public interest by presenting the facts of the matter, and one which allows the journalist a sliver of plausible deniability, because he follows the insular journalistic norm of both presenting both sides of the debate.

As such, we question New York University educator and critic Jay Rosen, who has argued that “neutrality and objectivity carry no instructions for how to react” to the rise of false but popular claims. We contend that the story is more complicated: Mainstream journalists’ figurative instruction manual contains contradictory “rules” for arbitrating the legitimacy of claims.

These contradictory rules are no doubt supported by public opinion polls taken during the August and September healthcare debates. Indeed, one poll released August 20 reported that 30 percent believed that proposed health care legislation would “create death panels.” Belief in this extreme type of government rationing of health care remained impressively high (41 percent) into mid-September.

More troubling, one survey found that the percentage calling the claim true (39 percent) among those who said they were paying very close attention to the health care debate was significantly higher than among those reporting that they were following the debate fairly closely (23 percent) or not too closely (18 percent).

Yet, of course, our data does not allow us to say that these numbers are a direct result of the mainstream media’s death panel coverage. Nonetheless, because mainstream media content still powers so many websites’ and news organizations’ content, perhaps this coverage did have an impact on public opinions to some indeterminable degree.

One way of looking at the resilience of the death panels claim is as evidence that the mainstream media’s role in contemporary political discourse has been attenuated. But another way of looking at the controversy is to demonstrate that the mainstream media themselves bore some responsibility for the claim’s persistence.

Palin’s Facebook post, which popularized the death panel catchphrase, said nothing about any specific legislative provision. News outlets and fact-checkers could examine the language of currently debated bills to debunk the claim — and many did, as our data demonstrate. Nevertheless, it appears the nebulous “death panel bomb” reached its target in part because the mainstream media so often repeated it.

Thus, the dilemma for reporters playing by the rules of procedural objectivity is that repeating a claim reinforces a sense of its validity — or at least, enshrines its place as an important topic of public debate. Moreover, there is no clear evidence that journalism can correct misinformation once it has been widely publicized. Indeed, it didn’t seem to correct the death panels misinformation in our study.

Yet there is promise in substantive objectivity. Indeed, today more than ever journalists are having to act as curators. The only way that they can effectively do so is by critically examining the surplusage of social media messages, and debunking or refusing to reinforce those messages that are verifiable. Indeed, as more politicians use the Internet to circumvent traditional media, this type of critical curation will become increasingly important.

This is — or should be — journalists’ new focus. Journalists should verify information. Moreover, they should do so without including quotations from those taking a stance that is demonstrably false. This creates a factual jigsaw puzzle that the reader must untangle. Indeed, on the one hand, the journalist is calling the claim false, and on the other, he is giving inches quoting someone who believes it’s true.

Putting aside the raucous debates about objectivity for a moment, it is clear that journalists in many circumstances can research and relay to their readers information about verifiable fact. If we don’t see a greater degree of this substantive objectivity, the public is left largely at the mercy of the savviest online communicator. Indeed, if journalists refuse to critically curate new media, they are leaving both the public and themselves in a worse off position.

Image of Sarah Palin by Tom Prete used under a Creative Commons license.