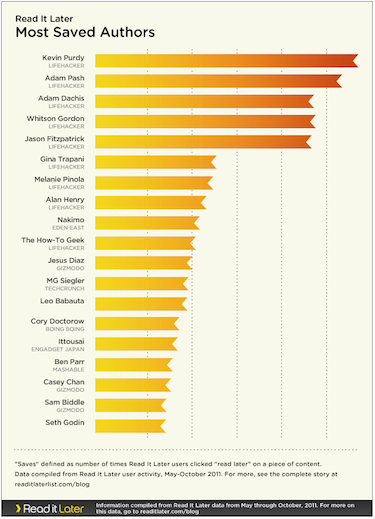

This morning, Coco Krumme and Mark Armstrong — newly of Read It Later and always of @Longreads — released a study of Read It Later data examining stories that were saved by Read It Later’s 4 million-and-counting users over a six-month period (from May 1 to October 31, 2011). Together, David Carr put it, the data are part of a broader group of statistics that are emerging in the digital space to lend insight into “what kind of writing and writers are the stickiest.” (More bluntly: “What Writers are Worth Saving?“)

This morning, Coco Krumme and Mark Armstrong — newly of Read It Later and always of @Longreads — released a study of Read It Later data examining stories that were saved by Read It Later’s 4 million-and-counting users over a six-month period (from May 1 to October 31, 2011). Together, David Carr put it, the data are part of a broader group of statistics that are emerging in the digital space to lend insight into “what kind of writing and writers are the stickiest.” (More bluntly: “What Writers are Worth Saving?“)

While the findings about overall article saves are pretty fascinating — go, Denton and Co.! — what I’m most interested in are the sample’s return rates, the stats that measure actual engagement rather than one-off story saves. Because, if my own use of Read It Later and Instapaper are any indication, a click on a Read Later button is, more than anything, an act of desperate, blind hope. Why, yes, Foreign Affairs, I would love to learn about the evolution of humanitarian intervention! And, certainly, Center for Public Integrity, I’d be really excited to read about the judge who’s been a thorn in the side of Wall Street’s top regulator! I am totally interested, and sincerely fascinated, and brimming with curiosity!

But I am less brimming with time. So, for me, rather than acting like a bookmark for later-on leafing — a straight-up, time-shifted reading experience — a click on a Read Later button is actually, often, a kind of anti-engagement. It provides just enough of a rush of endorphins to give me a little jolt of accomplishment, sans the need for the accomplishment itself. But, then, that click will also, very likely, be the last interaction I will have with these worthy stories of NGOs and jurisprudence.

(“Saving…saved!…gone!”)

It’s when I’m actually looking at my Instapaper or Read It Later queue that things get real. That’s when the Aspirational Read and the Actual Read duke it out for my attention. Do I really want to read about how GOP senators’ positions on Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are aligned with that of the industry? Or would I — alone with my thoughts and my iPhone — really kind of prefer to read something from The Awl?

It’s when I’m actually looking at my Instapaper or Read It Later queue that things get real. That’s when the Aspirational Read and the Actual Read duke it out for my attention. Do I really want to read about how GOP senators’ positions on Consumer Financial Protection Bureau are aligned with that of the industry? Or would I — alone with my thoughts and my iPhone — really kind of prefer to read something from The Awl?

This is what makes the Read It Later dataset so interesting. The line between the aspirational and the actual is thick: There’s precious little overlap between the most-saved authors and the authors with the highest return rates. “Engagement” isn’t really “engagement”; it’s not a static thing. What we think we want in a given moment — life-improvement advice, tech news — may well be quite different from what we want once we’re removed from that moment. (Which is to say: Interest, like everything else, is subject to time.)

What does endure, though, the Read It Later info suggests, is the human connection at the heart of the best journalism. While so much of the most-saved stuff has a unifying theme — life-improvement and gadgets, with Boing Boing’s delights thrown in for good measure — it’s telling, I think, that the returned-to content can’t be so easily categorized. It runs the gamut, from sports to tech, from pop culture to entertainment. What it does have in common, though, is good writing. I don’t read all the folks on the list, but I read a lot of them — and I suspect that the writing itself, almost independent of topic, is what keeps people coming back to them. When I’m looking at my queue and see Maureen O’Connor’s byline, I’ll probably click — not necessarily because I care about the topic of her post, but because, through her snappy writing, she’ll make me care. The Read It Later data suggest a great thing for writers: Stickiness seems actually to be a function of quality.

Or, as David Carr might put it: The ones worth saving are the ones being saved.