After a day of deliberating on Big Ideas — what is truth? how do we defeat its adversaries? what if they’re robots? — the academics and technologists at the Truthiness in Digital Media conference gathered Wednesday at M.I.T. to drum up real-world solutions to tractable problems. (The conference, co-hosted by Harvard’s Berkman Center and the Center for Civic Media, generated a lot of interesting blog posts. I live-blogged the event here.)

Facebook ads that target people likely to believe in political myths and hit them with facts. Common APIs for fact-checking websites. A data dashboard for journalists that guides the writing process with facts about subjects that appear in the text. “Pop-up” fact-checking that interrupts political ads on television.

While en route to the Truthiness hack day, I ran into Matthew Battles, managing editor at Harvard’s metaLAB and a Nieman Lab contributor. He had an idea for some kind of game, call it “Lies With Friends,” that would play on the joy in lying and, maybe, teach critical thinking. It would be like an online version of the icebreaker Two Truths and a Lie. Or maybe Werewolf.

We gathered a group to sketch ideas for two impossibly brief hours. First, the parameters: Would this game be played against the computer, a human opponent, multiple opponents? We settled on the latter, which fits with a socially networked world. Maybe it would be a Facebook app.

Would the game evaluate the veracity of players’ claims, or merely their persuasiveness? We picked the latter, because persuasiveness — not truth — is what wins debates. To quote Harry Frankfurt, author of On Bullshit (PDF):

Bullshitters aim primarily to impress and persuade their audiences, and in general are unconcerned with the truth or falsehood of their statements.

Indeed, that’s what Stephen Colbert’s “truthiness” means: “the quality by which one purports to know something emotionally or instinctively, without regard to evidence or intellectual examination,” he said in his show’s first episode. What we want to be true, not necessarily is true. Truthiness is a more effective political tool than truth.

That theme ran throughout Tuesday’s conference. It’s why fact-checking websites have not extinguished misinformation and have become themselves political weapons. Even Kathleen Hall Jamieson, founder of FactCheck.org, has argued fact-checking may perpetuate lies by restating them.

Truth is irrelevant. “We’re trying to ensure fidelity to the knowable.”

On Tuesday morning, Jamieson helped frame the conversation: “What is truth? That is an irrelevant question!” she said. “We’re trying to ensure fidelity to the knowable. That is different from the larger world of normative inferences about what is true and what is false. What is desirable and what is good is not the purview of FactCheck.org.”

Chris Mooney, author of “The Republican Brain,” said he used to be wedded to the Enlightenment view, that if you put forth good information and argue rationally, people will come to accept what is true. The problem, he said, is that people are wired to believe facts that support their worldview. It’s called cognitive bias.

Mooney described a phenomenon he calls the “smart idiots effect” — “the fact that politically sophisticated or knowledgeable people are often more biased, and less persuadable, than the ignorant.” He cited 2008 Pew data that showed Republicans with college degrees were more likely to deny human involvement in climate change than Republicans without — but the effect was opposite for Democrats.

Mooney turns to Master Yoda for wisdom: “You must unlearn what you have learned.”

Brendan Nyhan, a Dartmouth professor and media critic, conducted his own research: He gave a group of students bad information (President Bush banned stem-cell research) — and then provided a correction (no, he didn’t). Liberal students’ minds were unchanged, while conservatives were more likely to accept the correction as true. He calls this disconfirmation bias. Being told you’re wrong threatens our worldview and makes us defensive.

“People are much more likely to retweet what they want to be true.”

“In our effort to combat misinformation, if we’re not careful, we can actually make the problem worse,” he said.

Gilad Lotan, the chief scientist at SocialFlow, has access to a wealth of data from Twitter’s “firehose.” He demonstrated that false information often, but not always, spreads wider and faster than the eventual correction.

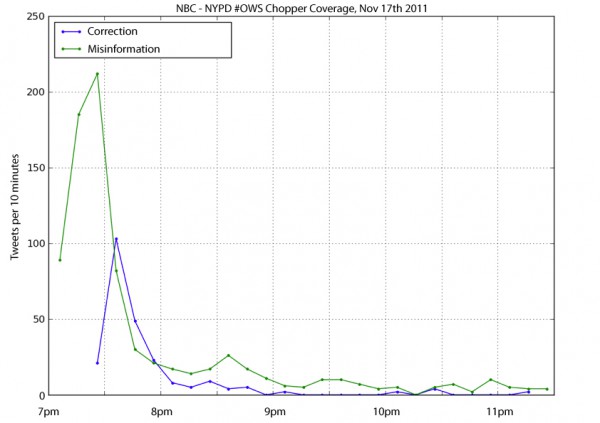

Take the case of @NBCNewYork erroneously tweeting that NYPD had ordered news choppers out of the air during Occupy Wall Street, less than a week after protesters were evicted from Zucotti Park. It was just the ammunition the OWS supporters needed, evidence of the NYPD’s evil, anti-speech tactics.

The NYPD replied on Twitter that it has no such authority, but it was too late. The data tells all:

The erroneous tweet appears to have spread faster and farther and had a longer tail than the correction. “People are much more likely to retweet what they want to be true,” Lotan wrote.

So that gets us back to the game. We wanted to create a game that challenges our cognitive biases and stimulates skepticism. (And hopefully a game that would be fun.)

We didn’t get very far on the execution. Perhaps a player would select a category and the computer would present two pieces of trivia, asking for the user to write in a third. Those items would be passed on to the next player, who would have to pick which claim to believe. Maybe it would be timed. We would build an experience that rewards players both for advancing claims (true, false, or otherwise) and for calling out bullshit. A leaderboard would show which claims traveled the longest and farthest and which friends were the most critical thinkers.

The hack day was more like a think day, one that I hope moves us to actually build something. I would like to try, when I get free time, but I would be delighted to see someone else beat me to it.