The developers behind Angry Birds said last August that players were averaging about 200 million minutes per day with the game. If that stat has held steady (and at the time Rovio said it was “growing exponentially”), it means that the world has played more than 300,000 years of Angry Birds.

In other words, stretched out linearly, our collective time spent flinging digital birds at pigs would predate the existence of modern humans. If you work in a newsroom, the thought of this level of audience engagement probably makes you swoon.

“The game industry is a $60 billion industry,” the Knight Foundation’s Jessica Goldfin told me. “When you talk about meeting people where they are, well, they’re playing games. Eleven million people play World of Warcraft…So how do you then take these mechanics, these games where people are, and build in some sort of higher social purpose or embed them within a social system?”

I recently caught up with Goldfin and the foundation’s Beverly Blake about a Knight-funded social-impact game called Macon Money, which was aimed at strengthening community ties and bolstering economic revitalization in Macon, Ga. This wasn’t a newsy experiment per se, but its focus on how to engage communities — and exploring new ways to connect them with one another — is in many ways applicable to newsrooms still finding their footing in an ever-changing digital media world.

“The goal was to create the environment where people who otherwise would not have had an opportunity to meet one another, to meet and get to know one another,” Blake told me. “The second goal was to use currency [invented for the game] to suport local businesses.”

So Knight — full disclosure: this site is, like many in journalism, also a Knight Foundation grantee — enlisted the game-design team at Area/Code, which has since become Zynga New York. In all, Knight granted about $700,000 for research and implementation. The result was a community-wide game called Macon Money designed to encourage divergent groups to come together, collaborate, and earn money that they would then spend at local businesses.

Here’s how it worked: Players who signed up would receive half of a Macon Money bond. It was up to them to find the person in their community who received the other half. Then, the newly formed pair could redeem their bond for Macon Money currency, which some local businesses agreed to accept. (A similar experiment — only without the gaming aspect — with local currency played out in Western Massachusetts about five years ago.)

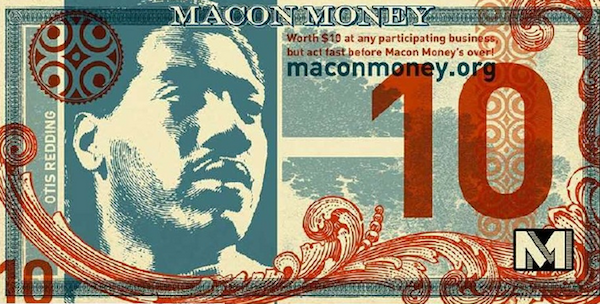

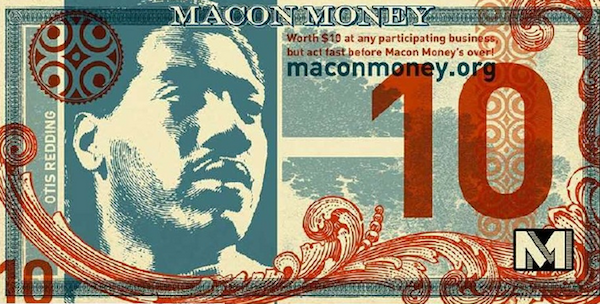

Macon bucks have an undeniably local aesthetic, with former resident Otis Redding’s image gracing the bills. The exchange rate is $1 USD to $1 Macon, and a total of $65,000 Macon Money bonds were issued in $10 – $100 increments. It was free to play, which Goldfin says made some participants dubious at first.

“We started out slow,” she said. “This was a brand new concept for all of us. There was a lot of apprehension about it and people thought, ‘Free money? I can spend it at these businesses? What’s the catch?'”

Over time, though, and with the help of word-of-mouth, traditional media coverage, informational videos, and boots-on-the-ground explanations from the team behind the game, people got “very excited, very involved, very committed to the game.” How the game spread reinforces the importance of multi-platform and multi-channel distribution when it comes to engaging an audience.

While gamification has creeped into the news world in fun and meaningful ways, the lessons for journalists from Macon Money have less to do with how newsrooms can use games in storytelling, and more to do with what games tell us about how people connect with one another and share information.

With its Games for Change initiative, Knight has spent plenty of time and money exploring and attempting to spur innovation in gaming that extends far beyond entertainment for its own sake. Here’s how the Knight Foundation explained how Macon Money fits into this mission earlier this week in a post-mortem about the experiment:

Unlike past foundation support for digital games, these took place in real-time with real people in the real world and they supported ongoing efforts to tackle local issues. There is already an existing body of research about how digital games have the potential to improve learning and influence behavior. But less attention has been paid to the effects of real-world games — i.e., games that are played out in the physical world. Knight wanted to explore which aspects of real-world games were most effective in addressing community issues.

Some of their findings: 78 percent of those who played Macon Money were under 40 years old; 70 percent were women; African Americans were underrepresented among players; most were employed full-time and earned more than $60,000 per year. Relatively few strong ties were formed, but about 15 percent of matched players became Facebook friends.

Blake says the overall results were “very encouraging,” because there was some evidence that the game forged and strengthened community ties: “When people get to know one another, even if it’s just a weak tie, that bodes well. Seventy percent of the people who responded on that note said that they would recognize the person [who had the other half of their bond] and say hello.”

The results were also positive with regard to economic development. About 46 percent of players said Macon Money took them to a local business that was new to them, and 92 percent reported having returned to that business after the game.

So what works — and what doesn’t — when it comes to audience engagement and community building in social-impact gaming? And how might these lessons be applied in newsrooms that want to launch games, or apps, or just generally rethink social engagement?

Goldfin offers what may be both the most obvious and most important point: “It was fun. Games are supposed to be fun. Often times, people are like, ‘We’re going to make a game about the First Amendment!’ or ‘We’re going to make a game about economic revitalization!’ Often the people who do that aren’t game designers.”

That brings us to some of the critical aspects from a development standpoint, like honoring the “value of design” by having the right people work on the right aspects of the project — then recalibrating as needed. For example, Macon Money needed seasoned game designers to build the infrastructure, but it also needed people who knew the Macon community first hand.

“You have to constantly balance, and manage, and negotiate the expertise of all of these elements,” Goldfin said. “Otherwise you won’t have success.”

The team also embraced an open source mentality, including sharing a blueprint for other communities interested in developing something simliar.

The project from the start required rethinking how to define the people that Macon Money aimed to reach, a task that is easily transferrable to “newsrooms that want to engage their constituents,” Goldfin said. When you start reconceptualizing how communities can be grouped, you can innovate cost-effective ways to reach them — whether it’s through games, content sections, events, tweet-ups, or some other channel.

“We usually define audiences or communities by very traditional demographics, but that no longer needs to be the limitation,” she said. “You can define communities through interest, rather than age. It’s the bigger picture. One size doesn’t fit all.”