Moving on from newspapers, journalism industry soothsayers are now predicting the decline of something much younger: the homepage.

As with newspapers — which haven’t so much disappeared as been pushed off center stage — few are saying that homepages will disappear completely. But as more people enter news sites sideways — via search engines, links they see in emails, or via Facebook and Twitter — newsrooms are finding their homepages aren’t the starting points they once were. And the propulsive growth of mobile devices has accustomed news sites to presenting more than one face to the digital audience, through some mix of mobile-optimized sites, native apps, and responsive design. (You now have news outlets talking about their desktop sites almost as an afterthought to mobile-first development.)

(I’m willing to bet that you got to this very article through some non-homepage channel; less than 7 percent of visits to Nieman Lab start on our homepage.)

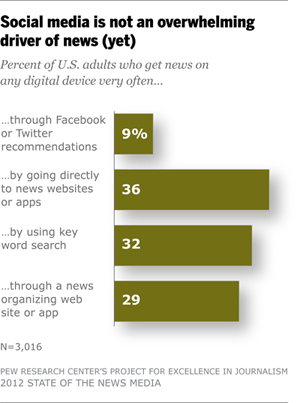

At the same time, traffic patterns seem quite divided between those who dive deep into social media and those who still head for news orgs’ front doors. Just 9 percent of Americans reported getting news through Facebook or Twitter “very often,” according to the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism’s 2012 State of the News Media Report.

Earlier this summer, we reached out to a number of news organizations to see what they’ve been seeing in recent months. Take The New York Times, for instance. In early 2011, the Times was typically seeing 50 to 60 percent of its visits come from people starting at the homepage of nytimes.com. More recently, that number had dropped a bit, with 48.6 percent of site visits starting there in March. Search engines drove 17.1 percent of traffic to the newspaper, and social is still just a blip: 3.1 percent of New York Times traffic came from Facebook, and 1 percent from Twitter.

Earlier this summer, we reached out to a number of news organizations to see what they’ve been seeing in recent months. Take The New York Times, for instance. In early 2011, the Times was typically seeing 50 to 60 percent of its visits come from people starting at the homepage of nytimes.com. More recently, that number had dropped a bit, with 48.6 percent of site visits starting there in March. Search engines drove 17.1 percent of traffic to the newspaper, and social is still just a blip: 3.1 percent of New York Times traffic came from Facebook, and 1 percent from Twitter.

But for brands that don’t have the history of the Times, the side door can be more important. At Buzzfeed, a whopping 37 percent of traffic comes from social networks and 17 percent from search, a spokeswoman told me. Of course, Buzzfeed makes virality a key tenet of news production — even if it means hooking readers with tacky celebrity photos and tags like “interspecies cuddling” — so it makes sense that social would be a significant part of how Buzzfeed distributes content. On the more muted side of the news, ProPublica tells me it gets “a lot more” traffic through search, social, and email than from direct-to-homepage visits.

Google’s Richard Gingras has argued that shifts in audience flow mean that we ought to be reconsidering “the very definition of a website,” and the possibility that it’s time to put “dramatically more focus on the story page” rather than the homepage. In a piece for Folio, Atlantic Digital editor Bob Cohn wrote that the homepage serves an important purpose as the “ultimate brand statement,” but isn’t nearly as important as a place to drive traffic.

In fact, a remarkable 88 percent of traffic to The Atlantic comes in sideways, meaning just 12 percent of site visits begin on the homepage. When I spoke with Cohn, he echoed Gingras on the importance of story pages, and said the homepage is a place to glean “the sensibility and the content areas of the site.”

“The trick is not to worry about where they’re coming from — the trick is what are they doing after they come.”

“The article page is now the principal way that people arrive at The Atlantic,” Cohn said. “The old mantra that every page needs to be a homepage has never been more true. People come for the article, and the goal is to give them a clean and interesting reading experience for the article — elegant, not too crowded, some art, a pull quote if the piece is long enough — and beyond that to make sure that we are giving the reader a sense of what else is on our site.”

Revisiting a series of questions Josh posed back in March 2011, I asked about a dozen news organizations for data detailing the following over the course of a recent 30-day period:

1. What percentage of your traffic comes from search engines?

2. What percentage of your traffic comes from facebook.com?

3. What percentage of your traffic comes from twitter.com?

4. What percentage of your site’s visits begin on your front page?

Only a handful gave me exact figures. But others were willing to speak generally about how traffic habits are changing, and what their organizations are (and should be) doing about it.

Raju Narisetti, managing editor of The Wall Street Journal Digital Network, says the shift away from the homepage is clear but that subscribers and non-subscribers frequent the homepage at different rates. (Narisetti broadly discussed traffic numbers in an interview, but The Wall Street Journal declined to provide specific percentages.)

“Sixty percent of our audience is not coming through the homepage, so already the majority is not experiencing the homepage,” Narisetti told me. “I’m more focused on the behavior of our subs versus our non-subs. Our subs come to the homepage in big numbers because they pay for it — they bookmark it. The non-subs tend to find out about our stories through other ways, so they come in sideways.”

He says social media traffic to the site accounts for anywhere from 6 to 10 percent. On the day after President Barack Obama announced his support for same-sex marriage, for example, social traffic was on the high end. (Narisetti attributes that spike in part to a Wall Street Journal Storify detailing Twitter reaction to the news.) But even as social grows, and people find their way to Journal stories without ever laying eyes on the homepage, Narisetti says it remains a critical area for editors to convey their news judgement.

“Ultimately, the curated aspect of the homepage brings people to big brands, right?” he said. “The trick is not to worry about where they’re coming from — the trick is what are they doing after they come. If they come sideways, can I get them to actually go to the homepage? That won’t happen if I diminish the value of homepage internally. I still need to make sure the homepage is engaging — just not get too hung up on people coming there first…It’s more of an engagement play than a front-door-audience play these days.”

“Anything we can do besides just words is something I’m thinking a lot about, and I think matters. We’re probably not doing it as fast as we should.”

Narisetti says the Wall Street Journal’s numbers are comparable with other big papers like The New York Times. His previous employer, The Washington Post, declined to share their traffic percentages. Its Beltway rival Politico would only provide wide ranges of traffic percentages. It said between 35 percent and 50 percent of its traffic begins at the homepage, for example. The Los Angeles Times was similarly cagey.

At a smaller outfit, ProPublica news apps editor Scott Klein, says publishing frequency affects readers’ traffic habits.

“ProPublica’s kind of the Galápagos Islands of news organizations,” he said. “We have very different species here. For most news websites, the homepage — because it changes so often throughout the news day and because so much of what they do is about what’s happening at this very moment — their homepages are where users tend to start. At ProPublica, we get a lot more traffic from social, search, links, and our email than we do through the homepage. But the homepage provides a crucial function, which is that it expresses the editor’s vision of the organization. And for somebody who doesn’t know who we are, it explains who we are, what we do, and how we do it.”

Klein said he wasn’t able to determine how many ProPublica readers start at the homepage, but that about 24 percent of traffic comes through search engines, 9 percent through Facebook and Twitter, and 8 percent via links in ProPublica’s email newsletters.

Everyone I interviewed agreed: The homepage can and should stay. But what needs to be done about story pages now that more and more readers are starting there? The Atlantic’s Cohn says one key is to bring in more photos and images.

“Less text and more visuals are going to help on most of our pages,” he said. “We’re not the text-heaviest site out there, but larger photos, better photos, more energetic ways of teasing other content. Headline fonts that convey the sensibility and the energy of the site. Anything we can do besides just words is something I’m thinking a lot about and I think matters. We’re probably not doing it as fast as we should.”

So when’s the redesign? “Calling it a redesign is too formal, too print-like,” Cohn said. “We’re constantly tweaking.”

Note: Data is from a variety of periods, varying by news site, in the first half of 2012. ProPublica couldn’t provide traffic data related to visits that begin on the homepage.

We’d love to know about traffic patterns to your site. If you’re willing to share, please leave answers to our four questions in the comments section. For some more guidance, check out this earlier post.