Crime reporters in Philly can thank Andrew McGill, who in his free time created a tool that scrapes docket sheets to produce a database of arrests in the city.

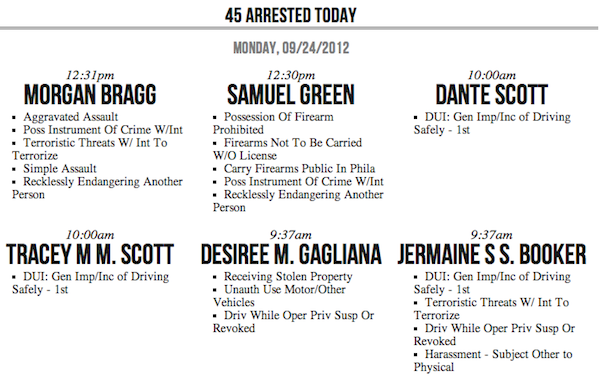

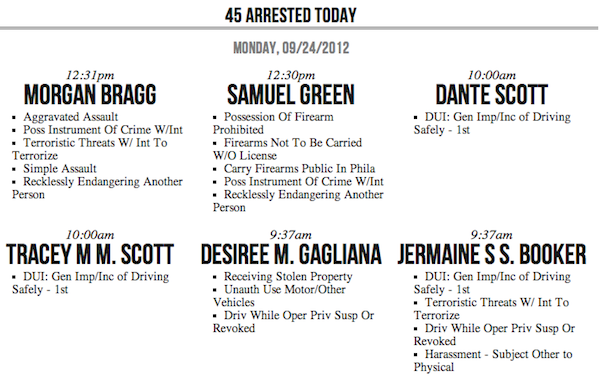

The result: Philly Rap Sheet, a responsive-design site that auto-tracks recent arrests by charges, name, age, hometown, bail range, and arrest date. New arrests are posted every half-hour, and alerts send customized updates — email me whenever someone’s arrested for trespassing — straight to your inbox. It’s a small entry in the growing tradition of data-journalism innovation on the cops-and-courts beat — from chicagocrime.org to EveryBlock to Crime L.A. and many more.

McGill made the site after having developed a non-public version of it for his newsroom at Allentown’s Morning Call. He took a reporting job at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in July, and is thinking about the next regional iteration of the site — and also grappling with some ethical questions related to it.

I caught up with him at the Online News Association conference in San Francisco over the weekend. Here’s our conversation, lightly edited and condensed.

Adrienne LaFrance: What made you want to build this?

Andrew McGill: In my other life, I was a general assignment reporter, so I was picking up the news of the day and making sure there weren’t any arrests in my section of Pennsylvania. It was really annoying because you had to go to the district justices’ offices and look through the reports and spend time and gas to get there.

Meanwhile, there’s this database the state has that lists all of the arrests, and there are all of these docket sheets — really good information — but it’s really hard to search by date. So you can’t really find out what the recent arrests are. If you know someone’s name you can get information, but you can’t really figure out the most recent things that happened.

So what I did, to save myself time and effort, I made it so a script would query this database every half hour to see if there were any new records at all. I brute-forced it: If there were, it would notify me. I was thinking, “Hey, this would be a tool that would be really helpful to people in larger communities like Philadelphia,” where I’m from. I wanted to see if it would work in a big city or if it would overwhelm the system. And I was curious about exactly how many arrests there are a day. That’s sort of how it was born.

Adrienne: So these are PDFs you have to deal with?

McGill: Yeah, but the nice thing is the URLs are formulaic, so if you know the docket number, every time someone’s arrested, it goes up by one. So I query that URL and I always add one, two, three, four, five to it. So, yup, these things are PDFs. It pulls it off from the server, parses it, and converts it to text. It basically scrapes the fields I want.

LaFrance: How did you decide on which fields to show? I know you list someone’s hometown, but you’re not putting up people’s home addresses for example.

McGill: Well, that’s partially because the data doesn’t have it. It’s kind of strange what these docket sheets do and don’t have. They don’t have race. It does have date of birth, so at least you can see the age range.

LaFrance: I was looking at

the graph and saw you even got a few as old as 70-something. Those 22-year-olds are out of control, though.

McGill: Oh, yeah.

LaFrance: What other demographic fields are on your wish list?

McGill: I really wish there was a specific address of crime. That’s really the motherlode. If you can say, “Okay, here’s a database of where all the crime in Pennsylvania happens,” that’s huge.

LaFrance: So the docs you’re dealing with don’t even include arrest location? That kind of thing would typically be in the public arrest log at a police station, right?

McGill: Nope, it does not. It has the arrest city. These records aren’t meant for reporters. They’re meant for courts people to look things up and follow the status of the case. Unfortunately, Philadelphia doesn’t really have an online system that has arrest data, so we have to rely on this state thing.

LaFrance: It’s a clever workaround at least. Have you seen any newsworthy names pop up yet — a mayor’s aide or something?

McGill: I don’t track it — it kind of does its thing. But I know people use it for news. Some friends of mine at the Inquirer use it. The Daily News, some folks monitor it there. Also the

Police Advisory Commission monitors it. I don’t know if there’s been a notable political arrest. I know they’ve used it to track down recent murders. A lot of times, it’s kind of uncanny — these court clerks will have entered the arrest information before the person’s booked. It’s a secret path into the mind of the court system. I do know there was one time that someone called

My Love was arrested at the airport.

LaFrance: That’s a good little back-of-the-book news item.

McGill: Well,

a Ken Jennings was arrested. And Ken Jennings the Jeopardy guy

tweeted and was like, “Guess I was arrested in Philadelphia,” and my traffic spiked a lot that day. It was not him, unfortunately. Well, not

unfortunately, but if Ken Jennings wants to joke about Philly Rap Sheet, he can do that. That’s just fine.

LaFrance: So what’s your vision for this thing?

McGill: I don’t know. It’s tough. I want to add historical data. So I spent a little bit of money to get data back to around 2005, which is not that far back, but at least it’s historical data. I want to backload that in. But in terms of the next step, it’s tough to say.

I want to get into a little bit more analytics. I think it’d be nice to add more realms of information to cross reference. I might look again at some things and see if I can pull some more data out of the existing sheets. Geography-wise, I do have what police district arrests are in, and I haven’t done a lot with that. So I want to try to start doing that, and maybe have a newsletter. Right now, I just have alerts.

LaFrance: And as a reporter, those are so helpful, I’m sure. You can be tracking all the murders.

McGill: That’s what I have set up for my alert. Unfortunately, it also pulls in attempted murder and stuff like that. I want to be able to get a summation newsletter out that you sign up for and say, “Okay, you’re in this neighborhood, and these crimes happened in your vicinity, and this is how it compared to last year,” and you would get this once a month or something. I don’t want to inundate people, but I think there’s room for a little more statistics pushing.

LaFrance: And in your current newsroom, any plans to build something similar?

McGill: I think the Post-Gazette probably would be interested in having something, and I don’t know if they’d want it to be open or not.

LaFrance: Aww, why not?

McGill: Well, I think it’s a powerful news reporting tool. And I think that it gives you an advantage over your competitors. In Philadelphia, I didn’t really have a dog in the fight. I didn’t live there at the time — I was in Allentown — so I was like, “Here’s a public resource everyone can use.” But now that I’m working for somebody, it would be to their advantage to keep it private. I haven’t really spoken to them — if I did something like that here — if they’d want it to be forward-facing or inward-facing. I think in terms of data being public, you want something to be out there. But in terms of news competition, you also want to keep your advantage.

There’s one interesting issue that I’m wrestling with, and that’s keeping names associated with crimes when there’s the real fact that people get their crimes expunged. So I’ve gotten calls and I’ve gotten one cease-and-desist letter saying, “Listen, my records have been expunged. Take down my name.”

LaFrance: Well, you don’t have to. It’s public record.

McGill: I don’t. It is public record. It’s like saying, “Hey newspapers, you put my name in an article, you have to take that down.” So I’m not legally obligated — but in a social justice kind of way, I don’t want to screw someone’s career up if they were wrongfully arrested or charges were dropped. If they’re clear everywhere else, but they’re on Philly Rap Sheet and someone finds that and says, “We’re not going to hire you.”

LaFrance: But how realistic is it for you to take the time to assess each claim of expungement?

McGill: It’s not. Fortunately, the one in which I received the cease and desist letter, they forwarded me the expungement notice. So that was helpful. I believe it was true.

LaFrance: Did you take that one down?

McGill: I didn’t take the arrest down. I would never take down the crime itself, but I made it so the name is not published. It’s still in my database, but it’s private. What I’m considering — I talked to an expungement lawyer, and he really was concerned about this — I’m considering having it so after a month the names are no longer included on the records. So you could still have the breaking-news aspect, but after a month you wouldn’t be able to search by name.

LaFrance: It’s hard.

McGill: I want to be as neutral an arbitrator as I can. And people are usually pretty sensitive about having their names associated with crimes. And again, I don’t want to mess up anybody’s lives. If I have the power to do less harm, I want to. But I also understand people are using this database to look for specific people.

So I’m trying to balance that with the chance that — the way the expungement lawyer explained it to me was that for a long time in Philadelphia, it was common practice in the District Attorney’s office to overcharge people. So if you were involved in a bar fight and you someone got hurt, you might get charged with attempted murder instead of drunk and disorderly. So on my site, you look like an attempted murderer. And I’m not going back and scanning thousands of docket sheets every month just to make sure nothing’s changed. I’m considering at least putting a link saying — I don’t know how to phrase it — but essentially, “If you had your record expunged, here’s a formal process to get in touch with me.”