Editor’s Note: The Nieman Foundation turns 75 years old this year, and our longevity has helped us to accumulate one of the most thorough collections of books about the last century of journalism. We at Nieman Lab are taking our annual late-summer break — expect limited posting between now and August 19 — but we thought we’d leave you readers with some interesting excerpts from our collection.

These books about journalism might be decades old, but in a lot of cases, they’re dealing with the same issues journalists are today: how to sustain a news organization, how to remain relevant, and how a vigorous press can help a democracy. This is Summer Reading 2013.

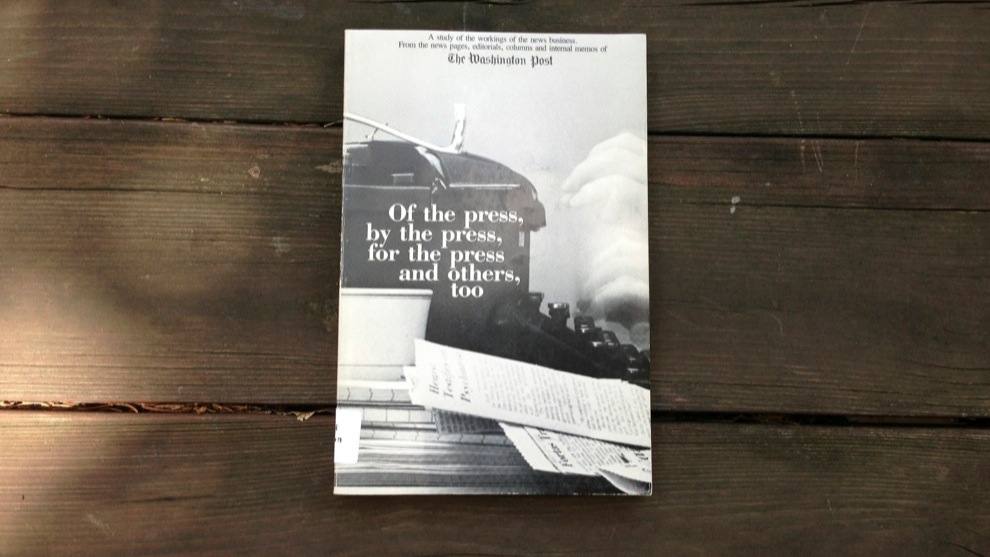

The introduction, by Washington Post editorial page editor Philip L. Geyelin, explains all of this, and also explains why it’s so important to report on the news. The media climate he warns of is eerily similar to that which we face today: the Obama administration is aggressively pursuing government employees who leak information to the press, and the professional access privileges of reporters are open to public debate.

The best defense of the press is self-reporting, Geyelin claims, backing his case with some choice quotations from Walter Lippmann. Geyelin’s introduction underscores the point that the current questions facing the press may be physically but not philosophically different from those of the past.

So what does this history tell us? That it is too hard? That the news business is better off covering everything but the news business?

The answer, it seems to me, is that it is obviously hard — perhaps too hard to sustain a regular thing — but that the concept of self-criticism is no less sound on this account and that the practice of it is no less needed in direct proportion to the amount of disfavor and distrust the press, for whatever valid or invalid reasons, may be encountering at a given time. For when the press is out of favor, people get to talking about doing something about it; at about that time, it seems to me, the press is well advised to start thinking in very serious ways of doing something of its own in the way of policing and examining and criticizing itself.

In Liberty and the News, published in 1920, Lippmann predicted that “in some form or other the next generation will attempt to bring the publishing business under greater social control. There is everywhere an increasingly angry disillusionment about the press, a growing sense of being baffled and mislead; and wise publishers will not poo-poo these omens.”

Lippmann accompanied this rather extraordinarily prescient warning with some sound advice. Publishers, he said, “might well note the history of prohibition where a failure to work out a program of temperance brought about an undiscriminating taboo…If publishers…themselves do not face the facts and attempt to deal with them, some day Congress, in a fit of temper, egged on by an outraged public opinion, will operate on the press with an ax.”

If that counsel was appropriate to the 1920s, the evidence of our senses commends it more than ever in the 1970s.