Editor’s note: This summer, we told you about the work of Sonya Song, the current Knight-Mozilla Fellow at The Boston Globe, who was working on a major analysis of what works and what doesn’t on Facebook when it comes to sharing news stories. She’s expanded that initial research into a deep look at the psychological motivations behind sharing and the touchstones that can make a post spread to new audiences. Here, crossposted from her blog, she summarizes her remarkable findings.

In the previous study, I presented data analysis that examined how users read and share Boston Globe posts on its Facebook Page. In this extended analysis, I’ve included qualitative analysis with a focus on cognition, content and emotion. My goal is to help newsrooms better promote their stories on and attract more attention from social media.

To achieve this goal, I’ve been digging into psychology literature for inspirations. Overjoyed, I’ve discovered some theories and findings that are portable to the social media environment:

Again, this report is based on the three key metrics featured by Facebook Insights: reach, engaged users, and talking about this. According to Facebook, reach is defined as “the number of unique people who have seen your post”; engaged users as “the number of unique people who have clicked on your post”; and talking about this as “the number of unique people who have created a story from your Page post. Stories are created when someone likes, comments on or shares your posts; answers a question you posted; or responds to your event”. These metrics are counted as absolute numbers of unique visitors in various ways and reflect user behavior from passive consumption to active interaction.

In the proto-analysis of Boston Globe traffic on Facebook, I reported the findings on image size and the “BREAKING” label. The general pattern is that illustrating a post with an image is associated with higher traffic compared to no image, so is a large image compared to a thumbnail. This pattern holds across three key metrics by Facebook (Figure 1). In addition, mere “BREAKING” is associated with a higher reach, although not with engagement or talking about this (Figure 2). In fact, not only BREAKING NEWS but also other uppercase words are associated with a higher reach, including WEATHER WATCH, MAJOR UPDATE, BIG PICTURE, NOW LIVE, etc.

As a hardworking journalist, you may tell me it’s upsetting to know that readers are attracted to this kind of superficial stuff like BIG PICTURES and BREAKING NEWS. But the good news for you is that the attention triggered by primitive tricks is fairly cheap. To gain more engaged attention, sophisticated messages would be a better choice, which we’ll discuss in the section on cognitive strain and System 2.

As a not quite positive example, MIT Technology Review may show us how to gain little attention. Look at its Facebook Page, we can see a lot of big T’s, certainly the logo of the magazine. It’s quite obvious that the stories are shared as links and the logo is automatically extracted by Facebook. As such, these stories have failed to have an interesting or simply relevant visual companion. The repeated T’s may also have turned the fans blind toward this symbol. The sad situation is that, even though the Review generates a lot of thrilling stories, its Facebook presence is far from compelling — you may have noticed the small numbers of shares and likes in Figure 3.

To understand how we deal with simple and complex stimuli (e.g., text, pictures, puzzles, etc.), Daniel Kahneman‘s (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow is a good read. In this book, Kahneman examines various theories and findings related to two thinking modes of humans: System 1 (fast) and System 2 (slow).

To understand how we deal with simple and complex stimuli (e.g., text, pictures, puzzles, etc.), Daniel Kahneman‘s (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow is a good read. In this book, Kahneman examines various theories and findings related to two thinking modes of humans: System 1 (fast) and System 2 (slow).

System 1 deals with innate skills that are crucial for survival and it works fast and automatically. One example is that we withdraw our fingers from fire before we realize what happened. Another one is to drive a car on an empty highway. System 1 is completely involuntary, for instance, when seeing 1 + 1 = ____, we feel compelled to fill in the blank. In other words, System 1 can’t be turned off, since it’s crucial for our survival. When hearing a sudden noise like an explosion, we’ll turn our heads to orient the source and wonder if danger arises. Besides innate skills, abilities gained through prolonged practice can also be handled by System 1, such as envisioning next steps for chess masters, or 210 = 1,024 for computer scientists.

By contrast, System 2 handles learned skills, such as a foreign language, logical reasoning, mathematics, etc. It’s slow and effortful, as how we feel when calculating 23 x 67 = ____. In other words, it demands much attention, like driving on the left if someone hasn’t done it before. Distinct from System 1, System 2 doesn’t always stand by and that’s why we are vulnerable to marketing and advertising techniques. In addition, System 2 can be refrained when we are tired, hungry or in a bad mood. Imagine how tough it is to take a test after staying up all night to prepare for it.

Between System 1 and 2, labor is divided. Most of the time, we’re on the fast mode of System 1. Meanwhile, System 1 assesses the environment and determines if it needs to call System 2 for extra effort. When difficulty, conflict and pressure are detected, System 2 will be mobilized and take control. System 2 processes information perceived by System 1 and corrects it if necessary. Also, System 2 overcomes the impulse of system 1. For instance, we have to make an effort to suppress emotions at work when an argument escalates. Hence, System 2 has the last word.

However, laziness is our nature as animals and we tend to retain energy for unexpected threats in the future. Since mental effort also consumes resources (e.g., glucose), it has limited capacity. Therefore, we by nature have a constant aversion to making efforts and let System 1 take the lead.

Now consider how we use social media: We browse posts fairly fast. Although occasionally we jump into an online debate, while quickly scrolling a large or small screen, we generally feel relaxed, relieved, and even pleased. In other words, we come to social media for an easy time rather than challenges.

This easy time on social media is what Kahneman (2011) calls “cognitive ease”. He describes cognitive ease as “a sign that things are going well — no threats, no major news, no need to redirect attention or mobilize effort” (p. 59). In other words, System 1 is in charge and System 2 is dozing.

Figure 4 illustrates a variety of causes and consequences of cognitive ease. (Maybe you have sensed the cognitive theories advertisers have been exploiting: Repetition, clarity, and happiness are more likely to make you feel better and persuade to believe some product or service deserves your money). Like clear display, legibility effects how easily we parse a piece of information.

Highly legible text will result in cognitive ease and pamper System 1 pretty well. Look at the following example given by Kahneman:

Adolf Hitler was born in 1892.

Adolf Hitler was born in 1887.

The experiment shows that more people would believe the first statement is true compared to the second — the fact is that Hitler was born in 1889. It’s as simple as you have guessed: the first statement is in bold font and is more legible.

If we port this psychological finding to social media, we may realize BREAKING NEWS is playing a similar role and thus attracting more attention, though nearly unconsciously. Since we can’t customize the size, color or font of text we publish on social media, using uppercase is the only option we change the level of legibility of our posts. If you’re desperate to overcome the barrier on social media, you may find lolcats inspiring.

If we port this psychological finding to social media, we may realize BREAKING NEWS is playing a similar role and thus attracting more attention, though nearly unconsciously. Since we can’t customize the size, color or font of text we publish on social media, using uppercase is the only option we change the level of legibility of our posts. If you’re desperate to overcome the barrier on social media, you may find lolcats inspiring.

Like uppercase text, large pictures are the same eye candy that soothes System 1 and attracts nearly unconscious attention from social media users.

Another way to cater to System 1 is to make the text simple and easy to parse. Readability is used to measure this aspect. A number of formulas have been established to measure readability.

As expected, number of average syllables per word was negatively correlated with all three metrics, namely “reach”, “engaged users”, and “talking about this”. The implication for social media editors is to prepare messages that cater to fast reading, because people are often guided by System 1 on social media, even though audiences of various media outlets name readable language at different levels (check out Figure 8 for the readability level across newsrooms). Presumably, once people are led away from Facebook, they will switch gear from fast to slow mode. But before that, each post has merely a split second to catch people’s attention.

On the subject of simple language, Orwell stresses that, regardless of literary use, simple words enhance language as an instrument of expressing thought. You may test yourself with the following example and see if you can smoothly slide your focus from the first to the last word of this sentence.

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

This paragraph is actually “translated” by Orwell from Ecclesiastes to make the point that text can be unnecessarily difficult. The original text reads as follow:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

To make Orwell’s point more precise, the original text scores at 18.5 while the translation at 27.5, based on the Flesch-Kincaid formula that I’ll cover in the section on cognitive strain and System 2.

Related to System 1, psychologists have discovered many interesting phenomena, such as priming effects. Priming effects is an overarching concept and discusses people’s behavior under nearly unconsciously influence. For instance, ask two groups of people to complete SO_P; before this task, one group saw EAT and the other saw WASH. The EAT group would more likely finish it as SOUP and the other SOAP. Here, EAT primes SOUP and WASH primes SOAP.

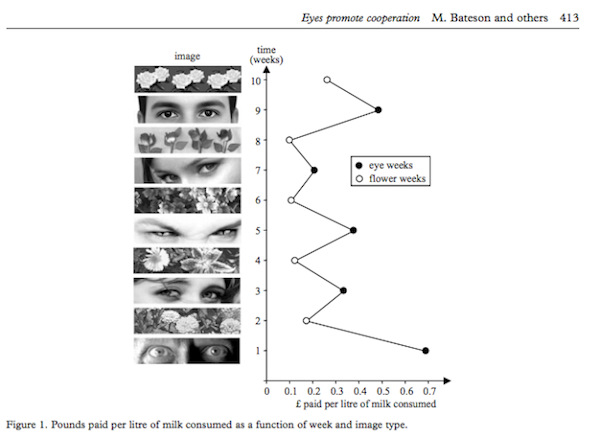

Another experiment relevant to unconscious influence was conducted at the University of Newcastle (Bateson et al., 2006). An honesty box was placed in office to collect payment for tea and coffee. Different posters were displayed in turn above the price list. The posters had no text but featured two themes, eyes or flowers. The results (Figure 5) showed that during the “eyed” weeks, more money was paid than the floral weeks. This experiment nicely demonstrated that “priming phenomena arise in System 1 and you have no conscious access to them” (Kahneman, 2011, p. 57).

Figure 5: Eyes on you, Bateson et al., 2006

If we apply this concept to social media, what could we find? I started exploring evidence with a small task. The research question is: Could questions raised on social media prime people’s behavior of answering them? That’s to say, would a question mark generate more comments on a post?

Yes, questions were significantly correlated with more comments (note: not with likes or shares), after controlling news section, sharing time and other factors. The general pattern is that more reach is associated with more engagement and more engagement with more likes, shares and comments (see Figure 10). The posts with a question, by contrast, more likely appear above the trend line, indicating better performance, despite some outliers beneath. Based on a sample collected within two weeks, the posts with a question is associated with 80% more comments.

Again, the notion for this finding is that don’t overuse it like the temptation from BREAKING NEWS. Although people say there’s no such a thing called a dumb question, you’ll be well aware when your question isn’t that smart. In addition, “the effects of the primes are robust but not necessarily large” (Kahneman, 2011, p. 56). That suggests that content itself remains the main drive for the traffic, while promotions help to some extent.

In discussing a variety of priming effects and anchoring effects, two phenomena related to the fast thinking mode (System 1), Kahneman notes that it’s human nature to be influenced unconsciously, although we can make extra effort to rein in our System 1. The following quote should ease both readers and journalists who may have developed moral concerns over these findings:

Your thoughts and behavior may be influenced by stimuli to which you pay no attention at all, and even by stimuli of which you are completely unaware. The main moral of priming research is that our thoughts and our behavior are influenced, much more than we know or want, by the environment of the moment. Many people find the priming results unbelievable because they do not correspond to subjective experience. Many others find the results upsetting because they threaten the subjective sense of agency and autonomy…If the stakes are high you should mobilize yourself (your System 2) to combat the effect. (p.128).

Now you hardworking journalists are about to learn some encouraging and exciting findings of this research: Your sophisticated messages deserve more attention, not necessarily of higher quantity but probably of higher quality.

In contrast to cognitive ease, cognitive strain has the opposite causes and consequences (Figure 7). Guided by System 2, people get more vigilant and make fewer errors, but meanwhile become less creative and feel more effortful.

Given the pretty flowchart, in practice, how shall we activate System 2 and engage people’s slow thinking? Here’s an interesting experiment. There are some tricky questions that people often get wrong. Three of them are included in Shane Frederick’s Cognitive Reflection Test. This test is so tricky that even students from top schools would give wrong answers. However, when the test was given in a washed-out poor print, the error rate dropped from 90% to 35% (Alter et al., 2007). This experiment has demonstrated that cognitive strain mobilizes System 2 and System 2 engages slow and careful thinking.

On social media, what kind of cognitive strain can we use to engage readers? More complex text may be one way to do it, such as sentences with more words and words with more syllables.

To measure the complexity of the text on Facebook, I adopted the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level in my study. This instrument has been tuned to reflect the number of years of education a US reader needs to understand the given text. For instance, an article scored 5.2 can be understood by fifth graders and above. The F-K Level is built upon the average number of syllables per word and the average number of words per sentence and calculated as follow:

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level = (11.8 * syllables per word) + (0.39 * words per sentence) – 15.59

On Facebook, various media outlets present themselves quite consistently with the styles reflected in their own publications. The readability scores in Figure 8 are calculated with the latest 200 posts from the Facebook Pages of seven media outlets.

Figure 8: The median score of Flesch-Kincaid. BuzzFeed: 4.83, Boston.com: 6.01, Boston Globe: 7.23, Washington Post: 7.37, CNN: 9.69, New Yorker: 12.91, The Economist: 14.62.

Here comes the exciting news for journalists. More complex text was correlated with more comments (note again: not with shares or likes)! The effect was modest though: 12 more points in the F-K Level was correlated with 12% more comments. In Figure 9, saturation and size of dots indicate the readability score of posts. Larger and more saturated dots more likely fall above the trend line, indicating better performance.

The fast and slow thinking modes may help interpret this evidence. When the text appears difficult, some social media users give up and march on to next posts. Those who decide to read the complex posts are in fact engaged in slow thinking and slow thinking allows them to understand the message better and to form an opinion. Hence, like poor print is correlated with better answers, complex text appears to be correlated with more comments from readers.

Besides the psychological perspective, other factors may help explain this evidence as well. The overall complexity of the text may imply the importance of a post, and therefore more complex text may attract more views and clicks. And complex messages tend to be longer, and longer messages are displayed in larger blocks of text. As such, more complex and thus longer posts take slightly more time for Facebook users to parse and therefore attract slightly more attention. These two parameters (importance of a message and parsing time) were not controlled in my statistically analysis, so their effects couldn’t be ruled out.

The general pattern between the three Facebook KPIs is that more reach is associated with more engagement and more engagement with more likes, shares and comments (Figure 10). This trend appears in a roughly linear relationship, between reach, engaged users, and talking about this (after log-transformed). Meanwhile, we can easily discern outliers above and beneath the trend lines. So why did those stories generate fewer activities?

To quantify this question, some people have developed a metric called conversation rate. This metric is calculated as the ratio of “talking about this” to “reach”. I’ll list the least as well as the most conversational stories and give a quick summary of the observed patterns in the content. Let’s first look at the most and least conversational stories and try to investigate why they turned out to be so.

Here is my quick summary of patterns related to conversational potential of stories.

The least conversational? Stories that were arts related (music, movies, books, etc.) or focused on strictly factual information (sports scores, settled business deals, etc.)

The conversations may also be explained through the fast and slow thinking framework. Two cases of beautiful photos (swans and lilacs) likely attract System 1 and help with conversations. By contrast, the other eight top conversational stories don’t feature beautiful photos at all. Instead, they first present a problem (tied-game, tornado, cancer, disconnection, etc.) and then provide a solution or a triumph. This pattern I name as tension-relief, which is combined by a turning point. As a turning point disrupts the flow of a message, it may slow down people’s thinking and engage System 2.

To sum up, there are various ways to attract attention on social media. Beautiful photos, simple messages and uppercase words likely attract System 1 for some unconscious attention. To attract more conscious and meaningful attention, we can address surprises, sophisticated language, and turning points in our messages. Both approaches would help gain more attention and thus more traffic on social media (see Figure 11).

Some may say these approaches are deceitful. I believe, however, the judgment hinges on the goal. If our goal is as sincere as to reach out to a larger audience and increase the civic impact of a newsroom, the use of these techniques is justified and appropriate. Here I want to quote Kahneman’s thought on this:

All this is very good advice, but we should not get carried away. High-quality paper, bright colors, and rhyming or simple language will not be much help if your message is obviously nonsensical, or if it contradicts facts that your audience knows to be true. The psychologists who do these experiments do not believe that people are stupid or infinitely gullible. What psychologists do believe is that all of us live much of our life guided by the impressions of System 1…

—How to write a persuasive message

Daniel Kahneman (2011, p. 64)

There are three ways for people to express on Facebook: like, share, and comment. In general, likes exceed shares and comments, because it’s the cheapest expression people can afford, except some cases when the messages are negative or controversial (Figure 12), which make a “like” contradictory to people’s cognition. This finding isn’t unique to Facebook but other online media as well. On YouTube, despite a large number of views, a thumbs up or down accounted for only only 0.22% of the total views, and comments accounted for a smaller ratio of 0.16% of them would leave a comment (Cha et al., 2007); on Wikipedia, 4.6% of the visits were related to edits; on Flickr, 20% of users ever uploaded photos (Auchard, 2007).

The question becomes tricky when I ask which number is larger, comments or shares. The best answer to it is: It depends. In Figure 12, the line marks shares matching comments; above it more shares and below it more comments.

Here’s a pair of cases (Figure 13). The first post is a Rolling Stone cover featuring the Boston bombing suspect. It collected about 600 comments and 100 shares (you may also notice that it only got 57 likes, fewer than both shares and comments). The second example is an alternative cover featuring the hero police and the victims, which attracted about 100 comments and 600 shares. These two posts are about the same topic, but the activities they induced are distinct.

To answer why people react by sharing or commenting, let’s examine more examples. They’re extreme cases where shares exceed comments the most and the opposite.

One perspective for examining the 20 posts listed above is emotion. Some psychologists study the relationship between emotion and dissemination of information (Rimé, 1991; Peters, 2009). When stories are episodes about other people, emotions would play a role as follows:

Some scholars have already applied emotion research to the media sphere. For instance, Berger and Milkman (2012) have examined 6,956 articles collected from the front page of The New York Times and the frequency of email shares. They have found that high-arousal emotions were associated with more email shares, including both positive (awe and amusement) and negative (anxiety and anger) emotions. In addition, the investigators found readers were likely to share a story when it became less emotional. They have controlled other factors like position on the front page and discussed the complex relationship between emotion and transmission of information. Their findings are in line with prior ones conducted in an offline setting.

Please note this study was carried out in 2008, when the investigators focused on new media rather than social media and on narrowcast via email rather than broadcast via social media. Still their findings have implications on social media. From the above 20 posts on Facebook, we can also observe a pattern related to emotions. Happy (gay marriage, Red Sox victory) and interesting (best fireworks, two-headed turtles) stories were shared more than commented.

By contrast, sad (death, loss) and contemptible (various suspects, sport scandal) stories were commented more than shared.

Looking at Facebook, we recognize it as a venue connecting friends and family members. This characteristic may contribute to the divide between shares and comments, because commenting would allow users to keep their involvement within a semi-anonymous space and away from their friends and families.

There may be other reasons explaining why some stories are more sharable than others on Facebook. Facebook is famous for a positive emotional climate (Pew Research, 2012) and harmonious social relations. (Guess why no dislike button has been ever introduced to Facebook.)

There are a variety of motivations we can suspect why we prefer to maintain good social relations. Some scholars believe good social relationships indicate interpersonal attraction and trust, help receive social support, and assist in transmitting information and resources crucial for professional performance (Podolny and Baron, 1997). Others name reciprocity, postulating that people give while expecting returned favors at a later point (Putnam, 1993).

As diverse as these motivations are, people generally aim to maintain good social relations. Hence, such behavior should also be observed on Facebook, a hub of social connections, and its users should try to please others and avoid offending them. That means, if a post warns of severe weather, people are more likely to share it among social connections (information exchange). On the other hand, if a political or religious story will certainly upset some users’ parents, friends, or bosses, they will feel reluctant to throw it in their faces by sharing it. Or if it’s aligned with the belief of a social circle (sports triumphs, gay marriage, sense of justice), sharing is preferred.

Nonetheless, when a story reads controversial and emotional, people develop a compulsion to voice their opinions. In these cases, we’ll notice a lot of comments generated under a post though it may not result in many shares.

Besides maintaining relations with others, people also tend to improve and mange their presence in social life. Goffman (1959) compares everyday life to theatrical performance; in both scenarios people recognize a specific setting and present themselves in front of a known audience. Not only through face-to-face interactions, people also attempt to build ideal self-images by associating themselves with tangible objects, such as branded goods. As Thompson and Hirschman note: “Consumption serves to produce a desired self through the images and styles conveyed through one’s possessions” (1995, p. 151).

Similar phenomena have also been observed on the Internet. For example, personal website owners may follow a motto that “we are what we post”, because they can manage their online self-images by presenting brand logos and products at whim, as opposed to a real life with financial constraints (Schau & Gilly, 2003). On dating websites, people get fairly cautious because profiles and photos are often carefully selected if not completely misleading. We have also heard that teens are obsessed with and exhausted by frequent improvements of their online presence. Similarly, we suspect that Facebook pages (brands, celebrities, news media, etc.) are also used to craft and improve people’s online presence, or an ideal self-image.

On social media, “I share therefore I am.” The news stories curated and shared by Facebook users inevitably signal their ideal self-images as well. Take Wired as an example, it frequently “geeks out” its fans. Complex circuits and charts are often highly shared, as shown in the following screenshots. I believe Wired has a high-tech audience, but still these “geeky” stories can be curated by non-technical readers as decorations.

Another example is the Facebook page of The New York Times, as shown in the following screenshots. Its posts that are hip and smart (science, health, cute tips) are highly shared.

In this post, I have highlighted my research on social media, especially how Boston Globe posts are perceived on Facebook. It’s a follow-up study after my first analysis that was focused on empirical evidence. Explaining why various types of reading and sharing behavior are observed is the aim of this study. The theories I’ve adapted and the conclusions I’ve reached include:

This guideline will go even longer as my research develops, but I by no means present it as a recipe that newsrooms should adopt strictly, because 1) overuse of these strategies may wear out readers and 2) creativity works best.

The purpose of this list, I think, serves as a nutrition facts label that helps newsrooms investigate why some posts take off while others never do — because you include or exclude some ingredients. Still, it’s completely up to individual social media editors to craft their best strategies to promote the already-published news stories.

That said, in my opinion, sharing news stories on social media may be more relevant to advertising than journalism, because the stories have been finished as a final product. Coming next is a battle for attention and an effort to persuade readers to share.

The statistical tool I used for this analysis is negative binomial regression to control the various aspects of news stories. The factors I’ve controlled are news section (defined by The Boston Globe) and share time in a day and the day in a week. When analyzing each of the three KPIs, I’ve controlled the other two. For more detailed explanation about omitted variables, please check the section on “Independent Variables, Dependent Variables, and Negative Binomial Regression” in my previous blog post focused on empirical evidence.

Another note is that Facebook has recently redefined the metrics, so future research may show different numbers. Nonetheless, the underlying theories should remain applicable, as we humans are quite persistent with our behavior.

As a Knight-Mozilla OpenNews Fellow, I’ve been receiving constant support from The Boston Globe and their support has made this research happen. I’m very grateful to the staff at the Globe for sharing the data with me, because their kind offer has helped me as well as many other newsrooms understand how people read and share news on social media. I hope this research helps secure its leading position in the online media world, not only through responsive design but also through strategic use of social media.

Working with The Boston Globe is a privilege, and this privilege is offered by OpenNews. I can’t express how grateful I feel to Dan Sinker and Erika Owens, the people behind the fellowship program, for their trust and support. This year has been amazing!

In addition, I want to thank Steve Wildman, my advisor at Michigan State University, for his continuous support in my research. Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, the book Steve recommended, has inspired me a lot in this research. I also want to thank Professor Ann Kronrod and my fellow student Guanxiong Huang at MSU. Their expertise in advertising and marketing has helped me enrich this research.