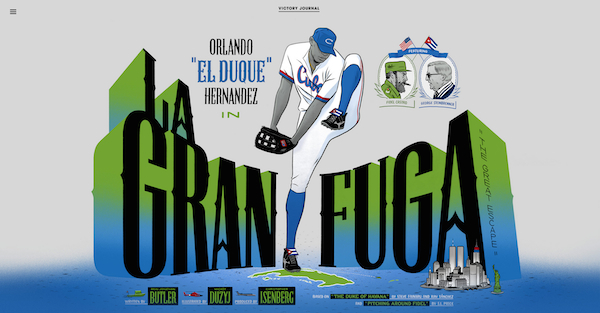

Statistics don’t matter to the sports magazine Victory Journal. Neither does the score of a game, really. Rather the magazine, which comes out in print twice each year, covers “eternal glories and ignominies of players and pursuits the world over.” It’s a different take on the saturated sports market — full-page pictorial spreads on Senegalese wrestling or Brooklyn expats who play handball in Miami Beach. And the magazine’s website features stories like a vividly designed 7,000-word profile of retired Cuban pitcher Orlando Hernandez’s defection from Cuba or an illustrated tale of a 1976 hockey game between the Soviet Red Army team and the Philadelphia Flyers that oozes with Cold War tension.

“We’re definitely diving into uncharted waters because we don’t want to make low-cost, high-volume content,” said Christopher Isenberg, Victory Journal’s co-founder. “We want to make high-cost, low-volume content, and that is what we are actively figuring out how to make work.”

High cost, low volume: That’s the philosophy across Isenberg’s network of projects. No Mas, an online boutique selling sports-themed apparel, memorabilia, and art that evoke “the thrill of victory and the ecstasy of defeat,” is the kind of place where you can purchase a $1,300 sweatshirt with “Cassius Clay” chainstitched across the front. And Doubleday & Cartwright, their creative agency named for two men each sometimes credited as the “inventor” of baseball, has done works for the likes of Nike and Red Bull and produces work with much of the same sensibilities of pieces in Victory Journal.

At a time when media companies of all sizes are trying to broaden their revenue streams — into areas like e-commerce and sponsored content — Isenberg’s already doing it on a smaller scale.

“We want to make the things we want to make by any means necessary because we feel they need to exist in the world,” he said. “And no one was just serving it up to us to get paid to do it. So I see see zero conflict, and they can be very complimentary. We enjoy both kinds of work [commercial and journalistic], and we have an incredible team that supports us in making both things a reality.”

About 20 people work in the office space Victory Journal, No Mas, and Doubleday & Cartwright share in a converted china factory in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg, not far from the waterfront. “There’s a fluidity to how staff works on various projects,” Isenberg said, adding that staffers will work on projects for all three entities, depending on what needs to get done.

Victory does things big. Its print edition is an oversized booklet printed on newsprint, and each of the magazine’s seven issues — the latest came out last month — feature one large photo on the cover beneath the word “VICTORY,” underlined and in bold capitalized letters. And each issue is full of photos that stretch across full spreads — about as visually lush as newsprint gets. Victory’s website, which adapts to mobile devices, has the same full-bleed feel.

In addition to the print magazine and its website, Victory Journal and No Mas have partnered with ESPN’s Grantland and its 30 for 30 documentary series to produce a number of animations, including an animated video telling the story of an IT manager who played a perfect round of putt-putt.

They’ve also done advertising work for ESPN, creating a series of ads with 72andSunny, another advertising agency, promoting the network’s WatchESPN streaming app.

Their work has been well received. Prior to the creation of Victory Journal in 2010, they ventured into content creation under the No Mas brand with a 2008 YouTube video, Dock Ellis & the LSD No-No, an animated short that chronicles the story of the late Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher who threw a no-hitter while on LSD. (The story may already be familiar to online journalism types; an ESPN interactive piece on Ellis in 2012 was something of a proto-Snow Fall.)No Mas’ video has more than 3 million views on YouTube and garnered an International Jury Prize in Short Filmmaking at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival. That’s there where Isenberg first connected with ESPN, as a 30 for 30 documentary was shown just before the screening of Dock Ellis.

The relationship has continued since then, with No Mas and Victory Journal doing work first with ESPN and then Grantland. Victory Journal is looking to pursue additional partnerships, including more work with ESPN, which is something both sides would be interested in, said David Jacoby, Grantland’s video/audio czar.

“They do a lot of storytelling, and at Grantland that’s what we try to do as well, storytelling,” Jacoby said. “What’s exciting about sports is the way you connect emotionally and how you draw ties to the rest of your life and your relationships…they’ve been doing that forever, and we do that at Grantland as well and that’s one of the reasons why we wanted to work together.”

The partnerships with ESPN provide Victory Journal with a platform significantly larger than its print circulation of 10,000. But Isenberg and Doubleday & Cartwright’s creative director Aaron Amaro, who also co-founded the organization along with Kimou Meyer, see Victory Journal as a labor of love.

“We are not so concerned about the revenue model right now,” Isenberg said. “We’re just trying to make this beautiful thing that we want to make and complete our vision and see what happens. It sounds a little bit vague as a financial strategy, but weirdly, that has worked quite well for us over time.”

The magazine has also offered Doubleday & Cartwright another avenue to highlight the type of work they do for clients, but Isenberg says that’s “a happy accidental byproduct…not the main point of it.”

And Victory Journal continues to define itself as it expands its focus to its web presence. It debuted its website last November, producing about two online pieces per month. Some pieces take days to produce, while others, between the reporting and writing and building the online presentation, can take months.

“We’re almost trying to create pieces that will stay there as monuments to something,” said Amaro.

For years, No Mas has produced video and animation pieces, and by expanding online, Victory Journal will be able to show off those types of stories, which they obviously could not have done before in print.

“We can’t put a moving image into our newsprint piece, so opening the possibility of having movement and sound — and not only translating flat storytelling in a beautiful way online and archiving it, but using the other possibilities that digital presents and being free from the logistics of having to get somebody a copy of it — is also nice,” Isenberg said.